April 1, 2020, marks the centennial of the birth of Toshiro Mifune, Japan’s greatest film actor and, arguably, the greatest film actor who ever lived. I first became aware of Mifune when his films played New York arthouse theaters in the 1960s and were advertised widely in the newspapers and sometimes reviewed in the local press. A number of older Mifune films got released for the first time in the U.S. during this period as the arthouse crowd became enamored of Japanese films and those of Akira Kurosawa and Mifune in particular.

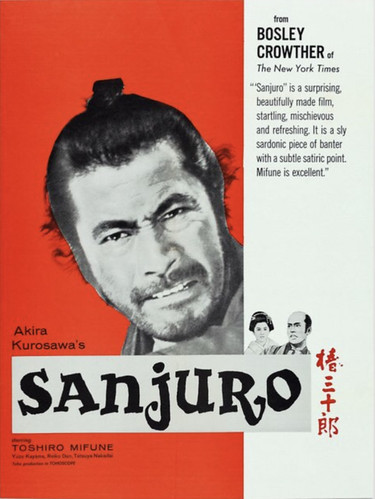

One reviewer, Leo Mishkin, covering the release of SANJURO in the Morning Telegraph of May 8, 1963 (a newspaper I don’t even remember), even complained about a glut of Kurosawa/Mifune films, since nine of them came out in the U.S. one after another in a period of three years (1961-64).

Here’s a sampling of Mifune films reviewed in local New York papers in the 1960s:

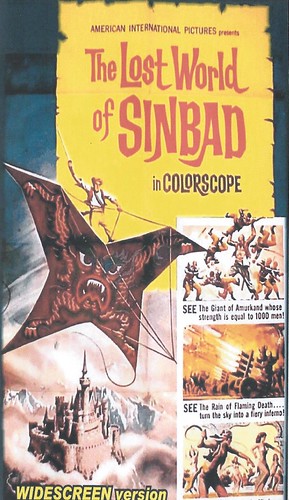

When I was ten years old, my parents bought me a double issue of Life Magazine specially devoted to the movies and published at the end of 1963. It had articles on DR. STRANGELOVE, NIGHT OF THE IGUANA and Natalie Wood, as I recall. The fold-out cover was a color picture of Toshiro Mifune strapped to a giant bamboo kite in a Toho Pictures production that Life Magazine casually described as “an oriental fantasy,” without giving a title. The actual film, SAMURAI PIRATE (1963), got released in the U.S. in 1965 by American International Pictures in an English-dubbed version called THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD. The cover of my copy of Life was torn away years ago, but I found a copy in the folder on Mifune in the research collection of the Library of Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and was allowed to photograph it.

The film is an Arabian Nights-style adventure offering fantasy elements, not at all unlike Hollywood’s Sinbad films, although Mifune’s character is a Japanese pirate named Luzon. As Stuart Galbraith IV points out in his book, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, after its theatrical run, THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD was quickly sold to television and offered many American movie-watchers their first exposure to Mifune. “Ironically,” says Galbraith, “more Americans were introduced to Toshiro Mifune through this tacky picture than through all his Kurosawa films combined.”

Here are shots from the scene in the movie featuring the kite, used to fly Mifune over a walled city to a castle roof from which he can rescue a princess in distress, although Mifune’s wearing a completely different costume than the one seen on the Life Magazine cover:

THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD never got reviewed in The New York Times and never played in any of my neighborhood theaters, as far as I knew, nor was I aware of any TV screenings. As intrigued as I was by that picture in Life Magazine, I didn’t get to see the film until I picked up a poor-quality bootleg VHS copy at Kim’s Video on St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan in November 2002. I found an import DVD of the original film, SAMURAI PIRATE, in Japanese with no subtitles, at a Chinatown store a few days later, so I rigged up a VCR with a code-free DVD player and watched the Japanese DVD with the English dub track playing over my headphones. Not the best way to see the film, but I finally saw it and reviewed it on IMDB. I would eventually get a copy of the Japanese original with English subs.

An earlier film of Mifune’s, STORM OVER THE PACIFIC (1960), was released in the U.S. in an English-dubbed edition in 1961 under the title, I BOMBED PEARL HARBOR. Mifune has a supporting role as Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, commander of an aircraft carrier during the Battle of Midway. I’m not sure how widely shown it was, but it eventually came out on VHS, which is how I finally saw it.

Mifune got considerable press in 1966 when, after years of turning down offers, he made his first Hollywood film, John Frankenheimer’s big-budget racing film, GRAND PRIX, which starred an international cast that included James Garner, Eva Marie Saint, Yves Montand, Brian Bedford, Francoise Hardy and Antonio Sabato.

Mifune played a Japanese automobile executive who wants disgraced American racer Garner to drive for him. I read the Mad Magazine parody of the film at the time and it included a gag about how Mifune’s character doesn’t speak a word of English when Garner first meets him, but is quite fluent in it in his next scene. I didn’t get to see this film until 50 years after it opened and found out that the parody was true! More on this later.

Two years later, Mifune starred with Lee Marvin in a film called HELL IN THE PACIFIC (1968), in which a Japanese officer and an American marine are stranded on a tiny Pacific island with no other people during World War II. After initially fighting each other and Mifune fending off attempts by Marvin to pilfer his supply of water, they wind up operating under a truce, each speaking their own languages and attempting to survive, eventually sailing on a raft together to another island to look for their armies. Marvin had been a marine during the war and was wounded fighting the Japanese on Saipan. Mifune served also, but on a base in Japan. One of his duties was sending teenage pilots off on suicidal kamikaze missions against American ships. The two men reportedly became good friends during the making of this movie. I saw this at a revival theater years after it first came out.

I had clearly been aware of Mifune for a long time before I finally got my chance to see him in a film for the first time in the spring of 1971. Down the block from my high school near Times Square in Manhattan was a tiny theater called the Bijou, located on the north side of 45th Street between Broadway and Eighth Avenue, which began a Japanese film festival on March 25. Here is the original newspaper ad I saw:

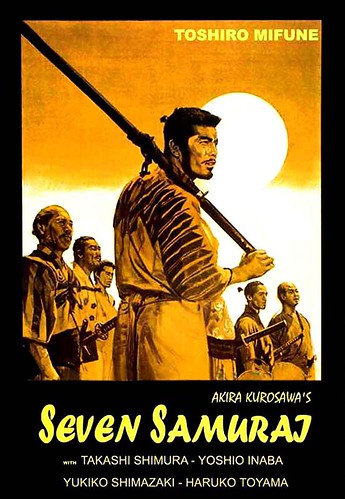

One of their offerings was SEVEN SAMURAI (1954), directed by Kurosawa and starring Mifune. Coincidentally, I had seen its western remake, THE MAGNFICENT SEVEN (1960), directed by John Sturges, for the first time just a couple of weeks earlier at the Victoria, a theater around the block on Broadway, on January 21. I had long been aware that the later film, which made stars out of Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn, was based on a Japanese film. And now, upon seeing SEVEN SAMURAI on April 8th at the Bijou, I got to see both on the big screen within three months. Later that season, the Bijou ran a double bill of two additional films directed by Kurosawa and starring Mifune, YOJIMBO (1961) and DRUNKEN ANGEL (1948), and I went to see them on July 17. Coincidentally, I had seen YOJIMBO’s Italian western remake, A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS (1964), directed by Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood, on May 20, at another theater around the corner on Broadway, the Astor. So I got to see SEVEN SAMURAI and its western remake and YOJIMBO and its western remake all on one small strip of real estate in Times Square in a matter of six months in 1971, while I was still in high school. What a film education.

As much as I enjoyed each of these films and would see them all multiple times over the next five decades, I have to admit that the Kurosawa versions, both in black-and-white, are richer in subtext, characterization and background detail. They’re not just action films or samurai films but tragic, darkly comic essays on human nature and the way people survived and lived in difficult times.

SEVEN SAMURAI:

YOJIMBO:

I should point out that the Bijou ran the full three-and-a-half-hour cut of SEVEN SAMURAI, which may have been the first time the full cut played theatrically in the U.S. Back in 1956, a shortened cut of two-and-a-half-hours played theatrically in the U.S. as THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN. Here is a shot of the marquee of the Apollo Theater on 42nd Street, which ran the film when this scene was shot for the 1957 TV series “Decoy” (three years before the American remake was made).

And here’s a poster for the film’s 1956 theatrical release:

SEVEN SAMURAI was an atypical role for Mifune in that he played the greenest member of the seven, a farmboy turned samurai wannabe who’s quite a pain at first and has to prove his worth to the group, which he does with great relish in the course of the narrative.

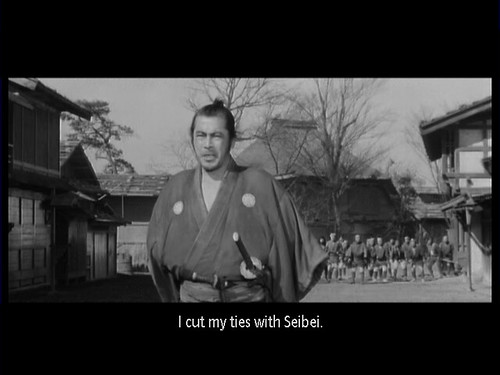

YOJIMBO offers Mifune in one of his iconic roles, as a wandering ronin (masterless samurai) eager to make a living with his sword, who enters a corrupt, lawless town and sees an opportunity to play two warring merchant families against each other for profit. Its cruel edge and black humor, as well as its visual imagination, were obvious influences on Leone. Kurosawa based the story on a 1929 crime novel by Dashiell Hammett called Red Harvest. (Hammett also wrote The Maltese Falcon, among other detective novels.)

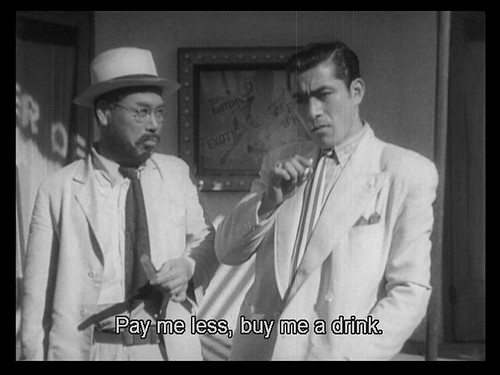

DRUNKEN ANGEL was a contemporary drama set in postwar Tokyo and features Mifune as a hard-living gangster afflicted with tuberculosis while the beleaguered, alcoholic doctor who makes it his mission to save Mifune’s life is played by Mifune’s mentor in SEVEN SAMURAI, Takashi Shimura. It was my first taste of the extraordinary versatility to be found in Mifune’s acting. (The same, of course, can be said of Shimura.)

Before this round of Japanese film viewing, I’d actually seen Takashi Shimura in a movie on television, as had many more Baby Boomer children. Since he was one of the stars of Ishiro Honda’s GOJIRA (1954), released the same year as SEVEN SAMURAI, he was featured prominently in the American re-edit, GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS (1956), which I’d seen on TV as a child. They even edited a scene to make it look like Raymond Burr was conversing with Shimura.

The next Mifune film I would see was RASHOMON (1950), the film that put Mifune and Kurosawa on the world map after it achieved international success in 1951 when it got widespread release, including in the U.S. It even won an Honorary Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film first released in the U.S. in 1951, the first Japanese film to attain that honor. (This was before Foreign Language was a competitive category.) I saw it on a double bill on December 2, 1971, with the first Ingmar Bergman film I ever saw, THE VIRGIN SPRING (1960), at the Carnegie Hall Cinema during my first semester of college. RASHOMON is, of course, the famous drama in which a bandit’s acts of rape and murder are viewed from several perspectives, all telling a different story. Mifune plays the bandit, seen here with Machiko Kyo, who died last year at the age of 95.

In 1972, both SEVEN SAMURAI and YOJIMBO played on the local public television outlet, WNET/Channel 13, and I watched them there. I saw SEVEN SAMURAI again when it played a second time in early 1973. As in my earlier theatrical outing, this was the uncut three-and-a-half-hour version. When SEVEN SAMURAI was reissued theatrically in 1983, the theater showing it in New York advertised it as the national premiere of the uncut version. I raised my eyebrows at that one.

On January 9, 1973, I got to see my first non-Japanese Mifune film and it was new in theaters. It was RED SUN, a European western produced by France, Italy, and the country where it was filmed, Spain, with a British director (Terence Young) and an international cast that included, along with Mifune, Charles Bronson, Alain Delon, Ursula Andress and Capucine.

For me, this was especially gratifying because it was the first and only team-up onscreen of a member of the original Seven Samurai, Mifune, and a member of the original Magnificent Seven, Bronson. (There would be other Hollywood films with Mifune in which another cast member of THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN was present, e.g. MIDWAY, with James Coburn, but none in which Mifune appeared onscreen with the American cast member as he did in RED SUN.)

Bronson plays an outlaw, betrayed by his confederates after a train robbery, who is forced to join Mifune on a quest to track the robbers and retrieve a samurai sword of gold meant to be bestowed upon the President of the United States as a gift from the Japanese Emperor. Mifune wants to complete the mission and restore his honor as a samurai or kill himself by seppuku, while Bronson wants to kill the outlaw leader who betrayed him, Gauche, played by French star Alain Delon (who had starred in a 1967 film called LE SAMOURAI and had already appeared with Bronson in a French film, ADIEU, L’AMI), and recover the money stolen from the train—for himself.

Bronson and Mifune travel on foot and then on horseback, learning how to deal with each other and, after difficult negotiations, strike a bargain that will enable Mifune to get back the sword and Bronson to kill Delon once he’s found out where the money is stashed. Mifune is an unlikely English speaker, but I was grateful that it’s his own voice and he wasn’t dubbed by another actor (more on this later). Bronson grows to like Mifune the more time he spends with him and even learns to trust him. There’s good comic interplay between them, including an interlude at a brothel where Capucine serves a meal to them and arranges for one of her new girls, Maria (Monica Randall), to bathe Mifune and get tips on Japanese lovemaking from him. It’s a very pleasant scene but precedes a new set of dangers awaiting our heroes in the morning, when Gauche’s men come looking for Cristina (Ursula Andress), his prostitute girlfriend.

At one point, Bronson tells Mifune, “You are one helluva man,” to which Mifune responds, “And you are one son-of-a-bitch!” Maybe not the English a non-native-speaking samurai would have used, but it got a big laugh in the theater. The two make quite a good fighting team as they encounter one obstacle after another, including another group of bandits, a war party of Comanche Indians, and worst of all, angry Cristina (Ursula Andress), who is taken hostage by Bronson to give him leverage with Gauche. It all culminates at an abandoned Catholic mission in Mexico where Bronson and Mifune are joined by Gauche and the other surviving outlaws and forced to team up one last time to withstand an attack by Comanches before the three leads get to settle their differences.

For many moviegoers in the U.S. in the 1970s, this was their first real glimpse of Mifune and the crowd at my neighborhood theater seemed very delighted with him. I watched the film again for this piece and enjoyed it as much as I did the first time.

This came at a time when Italian westerns frequently played neighborhood theaters, as well as other international hits. I’d already seen Alain Delon in a French crime thriller, THE SICILIAN CLAN (1969), at a neighborhood theater a few months earlier on a double bill with the Italian western BLINDMAN (1971), itself a takeoff on the blind Japanese swordsman named Zatoichi.

In 1974, I managed to take a crash course in Mifune’s masterworks when the Regency Theater in Manhattan began a two-month series of Japanese films.

It began on April 14 with CHUSHINGURA (1962), Toho’s epic three-hour film about the legendary 47 Ronin and their mission of revenge against the Shogunate official who caused their lord’s disgrace and subsequent seppuku. Toshiro Mifune appears as one of an ensemble cast of Toho stars and portrays an unaffiliated ronin sympathetic to their cause who blocks a bridge on the night of the raid so that the 47 can complete their mission uninterrupted.

Among the other Mifune films I saw that year were:

Hiroshi Inagaki’s SAMURAI Trilogy (1954-56)

Inagaki’s SAMURAI SAGA (1959)

Kurosawa’s SANJURO (1962):

Kurosawa’s RED BEARD (1965)

Kihachi Okamoto’s SWORD OF DOOM (1966)

Masaki Kobayashi’s SAMURAI REBELLION (1967):

Tadashi Sawashima’s BAND OF ASSASSINS (1970, aka SHINSENGUMI: ASSASSINS OF HONOR)

Eventually, I saw other Mifune films at revival theaters, including Kihachi Okamoto’s SAMURAI ASSASSIN (1965) and two by Kurosawa, HIGH AND LOW and THRONE OF BLOOD.

I’d return to several of these films when they screened at Japan Society or other specialized venues over the years, but for the most part, most of my Mifune watching over the past 20-30 years, especially first-time viewings, has been on home video. At last count, I had 51 of his films on either VHS, DVD or Blu-ray. (I’ve got SEVEN SAMURAI in all three formats.) I’ve still got five I haven’t seen yet, including three by Kurosawa (THE IDIOT, I LIVE IN FEAR, THE LOWER DEPTHS).

I’ve so far seen twelve Mifune films for this series of blog posts, two of which I’d never seen before. I had planned to see so much more, but it’s hard to concentrate amidst the turmoil of the coronavirus gripping the world right now as I write this and have to make and field calls to and from friends and family members checking in and sharing news. And Mifune had such a long and wide-ranging career, it’s hard trying to break it up into sub-themes. In future pieces, I’d like to focus on some individual non-Kurosawa favorites, such as Hiroshi Inagaki’s RISE AGAINST THE SWORD from 1966 (pictured below). These include a number I’ve seen for the first time in the past couple of years. These will be posted after his centennial.

For now I’d like to return to the subject of Mifune’s fate in English-dubbed versions of his films.

Mifune’s lines in many films are dubbed by ubiquitous voice actor Paul Frees, who was frequently heard on the dub tracks of numerous Godzilla movies released in the U.S., often attempting a Japanese accent. He dubbed Mifune’s lines in I BOMBED PEARL HARBOR and THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD. When we first meet Mifune in GRAND PRIX, he speaks Japanese only and it’s Mifune’s own voice. When we next meet his character, he speaks fluent English, just like in the Mad parody, only it’s the voice of Paul Frees. This is incredibly disconcerting and ruined Mifune’s role in the film for me. (It doesn’t help that it’s such a lethargic, overblown three-hour Hollywood melodrama to begin with.)

It’s even more distracting ten years later in the Hollywood film, MIDWAY (1976), in which Mifune played Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of Japan’s Pacific campaign in the war, and has a scene with numerous Japanese-American actors playing other officers (James Shigeta, Pat Morita, Clyde Kusatsu, et al). These actors all use their natural voices without accents only to have Mifune respond to them in Frees’ obviously dubbed, painfully accented voice. Mifune’s not in a lot of scenes, so it doesn’t ruin the movie.

Finally, there was a little-seen U.S.-Japan co-production, made in English, called THE BUSHIDO BLADE (1981, but produced in 1979), which used the framework of Commodore Matthew Perry’s second trip to Japan in 1854 and the historic treaty that resulted as a vehicle for a hackneyed potboiler that borrows a lot of its plotline from RED SUN, only this time it’s Americans tracking the sword thief in Japan. Mifune plays the Shogun’s Commander, another extremely unlikely English speaker, and is the one who signs the treaty with Perry (Richard Boone). The actor is dubbed in the early scenes, again, by Paul Frees, who adopts a much heavier accent to try and match Mifune’s and manages to sound less like Frees as a result, so it’s not too painful. In the signing sequence near the end, Mifune speaks his brief lines of English himself, making the scene a little more effective for me. It’s not a very good movie but, for now, it’s the only one that dramatizes the first official contact between the nation of Japan and the United States of America.

Here are links to my IMDB reviews of I BOMBED PEARL HARBOR, THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD, and THE BUSHIDO BLADE.

Here are some additional shots from my DVD of SAMURAI PIRATE (THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD), including Mie Hama as the princess who needs rescuing and Akiko Wakabayashi as her maid, both of whom would turn up as James Bond’s leading ladies in YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE (1967).

By my account I’ve seen 50 of Mifune’s movies. IMDB lists some titles only by their Japanese names, so I’ve probably seen more. IMDB lists 152 titles under the list of movies he’s acted in. That makes roughly 100 movies of his I haven’t seen. I’m sure many unsung gems are among them. I’m especially curious about this one, which got released in the U.S. theatrically, but never turned up on home video:

Interesting blog, it reminds me of what Kurosawa said about Rashomon :”These strange impulses of the human heart would be expressed through the use of an elaborately fashioned play of light and shadow. Light and shadow, represents not only good and evil, but also rationality and impulsiveness.”

I tried to write a blog about it, hope you like it too: https://stenote.blogspot.com/2018/04/an-interview-with-akira.html