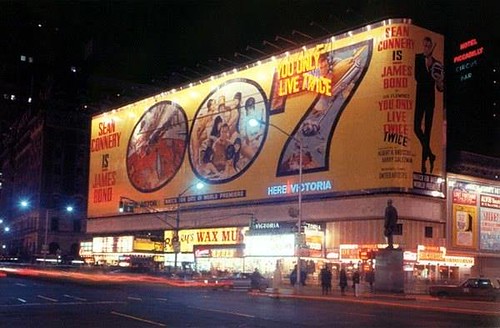

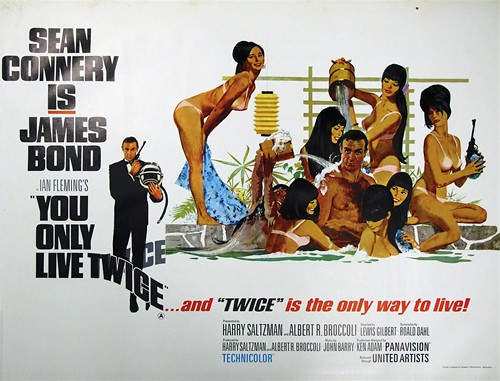

50 years ago today, on June 13, 1967, YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE (1967), the fifth of the James Bond films starring Sean Connery, was released in the U.S. It’s one of my favorite films and I’ve seen it over 30 times, probably more than any other film in my lifetime, and that includes WEST SIDE STORY (1961), THE WILD BUNCH (1969), KING KONG (1933), CASABLANCA (1943) and the second Bond film, FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE (1963), all of which I’ve seen close to or more than 30 times. Back then I had to wait to see YOLT until it came to a neighborhood theater in the Bronx in September of that year, but it would be the first Bond film I’d see during its initial release (I’d seen the others in reissues) and I was psyched for it from the beginning of its ad campaign. I remember visiting Times Square sometime that spring and seeing the massive billboard for the film adorning the full block of Broadway from 45th to 46th Streets atop the marquees of the Astor and Victoria theaters. The billboard had three distinct images from the film, all featuring Bond in unlikely poses, but promising action, sex and spectacle. Here’s a shot of that billboard:

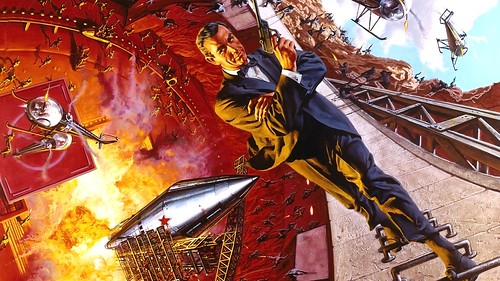

All three images were also used on ad and display posters:

It was the first big-screen film I would see with a Japanese setting and only the third overall, after GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS and RODAN, both seen on television. The film features four major Japanese characters, all played by Japanese actors, and included lots of location shooting in Japan, although Japanese interiors were mostly shot at Pinewood Studios in London. I remember marveling at how high-tech the Japanese Secret Service was, with copper-sphere video monitors showing multiple-angle surveillance footage, underground subway system offering a fully-equipped office inside a subway car, and such accoutrements as the video phone system in the Toyota sports car which one of the characters drives.

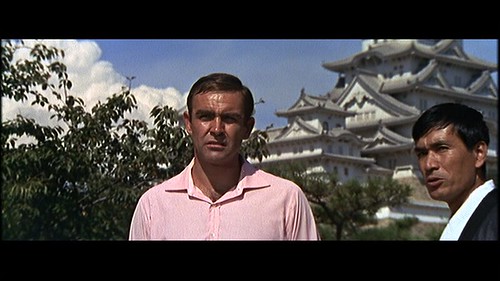

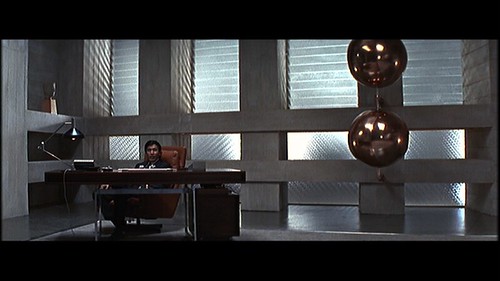

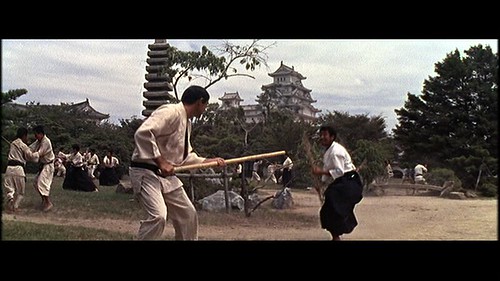

I was also struck by the beauty of the Japanese settings, whether actual locations such as Himeji Castle, where the ninja training academy is situated, the shrine where Bond’s wedding is staged, and the fishing village from which Bond conducts his search for the SPECTRE rocket base, or the studio interiors, including Henderson’s Japanese-style villa, Tanaka’s sprawling home, Osato’s streamlined office with traditional touches, and the simple tatami-matted bedrooms where Bond sleeps, first with Aki and then with Kissy.

YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE was the film that triggered my interest in Japan, first spurring me to read the book by Ian Fleming on which the movie was based and then, when I got the opportunity in the spring of 1971 during my last semester in high school, to see actual Japanese films on the big screen, starting with Akira Kurosawa’s THE SEVEN SAMURAI (1954) and YOJIMBO (1961). Eventually, I’d see many additional films featuring the Japanese stars of YOLT, Tetsuro Tamba, Akiko Wakabayashi, and Mie Hama. Of course, these were my first steps on the long road to further exploration of Japanese cinema and subsequent forays into anime, manga, super sentai, tokusatsu and J-pop. The rest, as they say, is history.

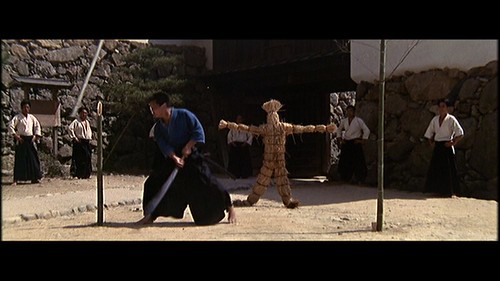

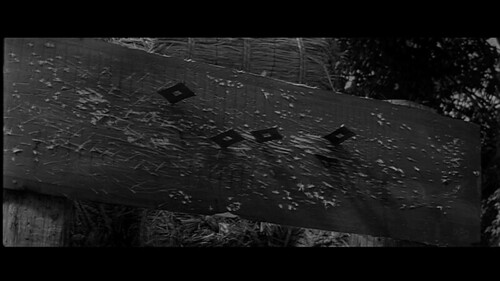

But as a 14-year-old sitting in the children’s section of the Fairmount Theater with my 12-year-old sister Claire, I was struck most during that first screening of the film by the martial arts action on display, from the judo Bond uses in a fight in Osato’s office to the swordplay demonstrated by the ninjas during a training demonstration and later in the battle at the SPECTRE rocket base to the various ninja arts shown, for the first time in a major Hollywood release, including the use of hooded ninja outfits, suction cups for climbing walls, and throwing stars. It wasn’t the first time Hollywood used Asian martial arts in a film, but it was the first time it played such a major role in the film’s action staging from start to finish. Numerous Japanese martial artists were employed and filmed in Japan and then brought to England for the battle at the rocket base. It wasn’t the first time audiences in America had seen ninja arts on screen–the little-seen Japanese animated feature, MAGIC BOY, boasted that distinction—but it was the first major film given a wide release in the west to demonstrate ninja arts by name. Certainly, I had never heard of ninjas before seeing this film nor had I ever actually witnessed samurai-style swordplay on the big screen before. I was intrigued and wanted to see more and eventually I did.

I first wrote about the film in my earlier blog entry, 1967: Action Cinema’s Greatest Year, and here’s what I recalled about the audience reaction at that first screening:

When the climactic assault by Bond and the ninjas on SPECTRE’s volcano rocket base began, the crowd in the theater went completely nuts. We’d never seen anything like this before and kids were roaring and applauding and cheering and jumping up and down like I’d never seen an audience react before. (Two little wise guys behind me simply exclaimed “Ooooh!” in unison every time something happened.)

I should add that the action finale drew similar enthusiastic responses whenever I saw the film in theaters back in those years. The first five Bond films were re-released to neighborhood theaters quite frequently back then and I went almost every time. (Any time United Artists needed a quick infusion of cash, they re-released WEST SIDE STORY, the Bond films or the Clint Eastwood “Man with No Name” Italian western trilogy.)

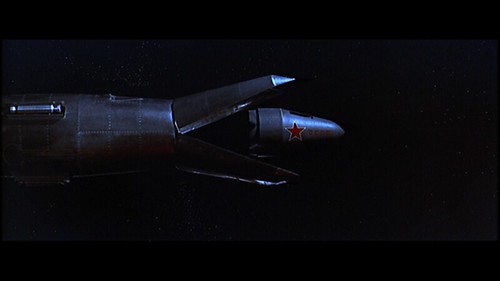

I’ve always found YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE to be the most suspenseful Bond film and the one with the most urgent premise. The international criminal organization, SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counterintelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion), is hijacking orbiting capsules from the U.S. and the Soviet Union with each country blaming the other and threatening war. The next scheduled launch, of a U.S. rocket, will trigger war if there’s any interference, so Bond has to confirm that SPECTRE is the culprit and work with the Japanese Secret Service, headed by Tiger Tanaka (Tetsuro Tamba), to locate and neutralize the rocket base, which has been identified by radar sources as being somewhere in Japan. The trail to SPECTRE begins with Tokyo industrialist Osato (Teru Shimada), who is shipping liquid oxygen to an island in Japan, evidently intended for the rocket base. Osato’s operatives put up quite a fight and Bond’s life is in peril more than once before he finally narrows down the location of the base to a volcanic mountain range near a remote fishing village on an island in western Japan.

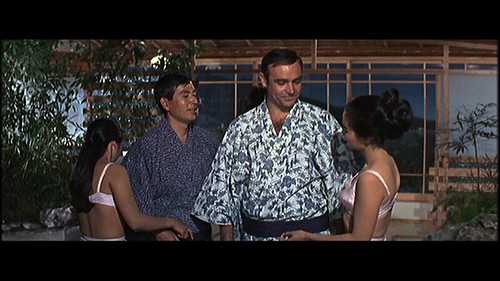

Bond works with two of Tanaka’s agents, Aki (Akiko Wakabayashi), with whom he has a romantic fling, and Kissy (Mie Hama), whom he “marries” in a staged ceremony meant to embed him in the island’s fishing community in order to have a cover while he searches for the rocket base. This occurs after he’s “transformed” by some mild cosmetic touches into an approximation of a Japanese man. Eventually, Bond and Kissy locate the volcano housing SPECTRE’s rocket base and Bond infiltrates the place while Kissy brings back Tanaka and his ninja army to raid the base and try and stop the completion of SPECTRE’s newest mission. In the course of it, Bond encounters his old nemesis, Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Donald Pleasence), the head of SPECTRE, who is supervising the mission from within the base. A spectacular action finale finds 100 ninja combatants taking on Blofeld’s army of guards and technicians, leading to gunplay, explosions, swordplay, judo and, finally, the demolition of the base.

YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE was the first of three Bond films directed by English director Lewis Gilbert, who, as of this writing, is still with us. I’ve always liked the flow of the film and the alternation between quiet scenes and exciting action. In between assorted fights, shootouts, car chases and a gadget-laden gyrocopter’s effective takedown of four armed SPECTRE helicopters, there are moments of downtime, such as the bath Bond and Tanaka take with the help of bikini-clad masseuses, the staged wedding between Bond and Kissy on the island, and Bond and Kissy’s early morning boat ride on the way to the volcano. For once in a Bond film, Bond never sets foot in England—or any other place in Europe, for that matter. Bond is more of a public servant here, working closely with his Japanese counterparts and never going off on his own or disobeying orders. He doesn’t display the British arrogance that you see hints of in his other films, an arrogance the working-class Connery always tended to downplay anyway. In this aspect, the film more closely resembles FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE (1963), in which Bond worked in partnership with Kerim Bey (Pedro Armendariz), the head of the Turkish Secret Service, and sought to blend in and be a good soldier. Interestingly, neither Turkey nor Japan were ever English colonies, so that may have something to do with it.

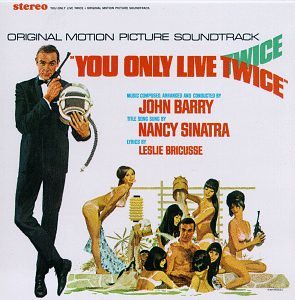

YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE has, arguably, the most beautiful title sequence of any Bond film (courtesy of Maurice Binder), accompanied by, arguably, the loveliest Bond title song, performed by Nancy Sinatra. John Barry’s score for the film is one of his most wide-ranging, with lyrical interludes, action accompaniment, sci-fi flavor, and suspenseful undertones. It was one of the first soundtrack albums I ever bought and even then I was disappointed that it did not include every cue in the film. I have some quibbles about the use of cues recycled from other Bond films for the “Little Nellie” helicopter battle, but overall I consider it Barry’s best score.

YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE doesn’t have the reputation among younger Bond fans that it does among those of us who experienced it in the pre-Roger Moore Bond era. One criticism frequently leveled at it involves the unconvincing Japanese transformation that Bond undergoes in the film. In an “operation” scene supervised by Aki, Bond is shaved of his chest hair, has something applied to his eyes, and is given a wig. It’s highly unlikely that anyone in the fishing village would have been fooled. Although Tanaka’s men have been sent to the village and ordered to blend in, a SPECTRE spy in the village would certainly have noticed something out of whack. So I’m not even sure what the point of it all is, especially since the countdown to the U.S. rocket launch is imminent. In any event, Bond’s “Japanese” disguise is completely gone by the time he infiltrates the SPECTRE rocket base. Still, the interlude in the fishing village, including the wedding ceremony, offers a tender sequence and a welcome lull in the action before the big finale.

Another criticism involves the portrayal of the Japanese women in the film as subservient to Bond and eager to bed him. At one point early on, when Bond and Tanaka get bathed by a quartet of masseuses, Tanaka declares that “in Japan, men always come first, women come second,” a sentiment endorsed by Bond. Curiously, the masseuse he chooses for his private session is obviously not Japanese. (The actress, Jeanne Roland, is half-English and half-Burmese.) Aki, for one, gets awfully affectionate with Bond right away, something I doubt Tanaka would have approved of, given her status as one of his top agents and his plan to have Bond “marry” another agent who is already stationed in the fishing village. She says to Bond, on his first night in Japan, “I think I will enjoy very much serving under you.” At least Kissy, on the night of their supposed honeymoon, puts up resistance to Bond and orders him to sleep by himself. She seems more affectionate in a later scene, although the two never actually get around to consummating their “marriage,” at least not during the film’s running time.

Tanaka’s sentiment about men coming first echoes one voiced by the same character in Ian Fleming’s novel where Tanaka upbraids Bond for being polite to women, saying: “First lesson, Bondo-san! Do not make way for women. Push them, trample them down. Women have no priority in this country. You may be polite to very old men, but to no one else. Is that understood?” It should be added that in the audio commentary on the DVD, Lewis Gilbert, the film’s director, recalled how actor Tetsuro Tamba, while filming in England, used to rush through doors ahead of women and not bother holding them open. When Gilbert gently chided him for it, Tamba said he simply couldn’t change his attitudes.

Connery does seem a little bored here. Others have noted this. He had difficulty dealing with crowds and paparazzi in Japan and seemed a little tired of his Bond-induced celebrity. Bond also seems more reactive in the film rather than proactive. His scenes with others are more low-key. He doesn’t really seem to connect with either Bond girl in this film, but that’s simply because they’re both on his side and they each know who he is prior to their involvement. They happen to be professional colleagues, rather than someone with a connection to the enemy whose loyalties had to be negotiated, like Tatiana (Daniela Bianchi) in FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE, Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman) in GOLDFINGER, or Domino (Claudine Auger) in THUNDERBALL. He has an easy rapport with Tanaka, but it doesn’t go as deep as his relationship with Kerim Bey in FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE, which involved moral dilemmas and life-or-death choices. Tanaka seems rather detached throughout YOLT.

The novel, however, is another story. Bond and Tanaka spend a lot of time bonding, so to speak, over bottles of sake and various Japanese delicacies. They discuss cultural differences between Japan and the west and Tanaka’s war experience, in which he was a spy serving abroad when he demanded to be called back to Japan and allowed to enlist as a kamikaze pilot. The war ended before he could fly his mission, leaving him with a sense of being cheated. You get the sense that if a straight adaptation of the book were made at the time, Tanaka would be played by one of those older, crustier actors we see in Kurosawa or Ozu movies. (If it was made that way today, I envision Takeshi Kitano in the role.)

I read the book eagerly as a 14-year-old, but I was disappointed at the time by the fact that the plot was so different from the movie and the mission was much smaller-scale. But at the same time I was grateful for all the insights into Japan that it gave me, insights I’ve gone back to and continue to try sorting out some 50 years later. I re-read the book for this piece. In it, Bond is sent to Japan to persuade Tanaka to give the British Secret Service access to the same intelligence channel that Japan is using to feed reports on Soviet activities to the CIA. Tanaka agrees to do so but only if Bond performs a task that the Japanese, for diplomatic reasons, are unable to fulfill themselves. They want him to kill a mysterious Swiss botanist, Dr. Shatterhand, who has taken up residence in an old castle in Fukuoka and created a garden filled with poisonous plants, insects and other life forms, all ostensibly for experimental purposes, but which has attracted record numbers of Japanese intent on committing suicide. When Bond arrives, the number of suicides reported by local officials is up to 500. The government wants something done about it that won’t involve them, so Bond is given the job. He reluctantly accepts, but when he learns that Dr. Shatterhand is his old nemesis, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, joined by his hideous wife Irma Bunt, he tackles the assignment with new relish.

The few elements from the book that remain in the film include the Japanese setting, of course, but also the ninja training academy where Bond has to learn some of the ninja arts for gaining access to Shatterhand’s castle and hiding amidst the poisonous plants of the garden in order to lay in wait and complete his job when the opportunity arises. The garden includes a pond stocked with piranhas, something carried over into Blofeld’s living quarters in the film, where he has a pool stocked with piranhas in his office and a trap door with which to deposit disloyal or incompetent employees into the pool.

The character of Henderson is retained. He’s an expatriate Brit in the movie (played by Charles Gray, pictured below), but an Australian diplomat in the book, called “Dikko” Henderson, and the man who arranges Bond’s audience with Tanaka. He is not killed in the book. He and Bond have some great exchanges about Japan and the war.

Aki is not in the book, but the Japanese woman whom Bond “marries” is. She’s never called by name in the film, but the character’s name in the book is Kissy Suzuki. (She’s just listed as Kissy in the end credits of the movie.)

In the book, she’s an Ama island girl who dives for shells and was once recruited to star in a Hollywood film and hated the experience so much she went back to her seacoast village with the money and took care of her family. She’s not an agent for Tanaka, but simply a family friend of the local superintendent, so she’s asked to put Bond up while he prepares his mission and aid him in crossing the water to the castle. (There’s no talk of marriage.) The only thing she liked about Hollywood was her friendship with actor David Niven (who, coincidentally, played one of several James Bonds in the 1967 spy spoof, CASINO ROYALE, the same year as YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE). After walking away from Hollywood, she was described in the press as “the Japanese Garbo.” When Bond suggests she revive her film career, she launches into a rant: “Never. I hated it. They were all disgusting to me in Hollywood. They thought that because I am Japanese I was some sort of an animal and that my body is for everyone. Nobody treated me honourably except this Niven.”

(I looked over the filmography of Niven, pictured above in CASINO ROYALE, on IMDB to see if there were any film he’d been in before the novel was written that featured an Asian female star, but I couldn’t find any, so I don’t know the basis, if there even is one, for his inclusion in the novel.)

Also in the book, Bond undergoes a “transformation” into looking Japanese that is tossed off in a few lines, a much less complicated process than in the film, but followed up a few pages later by Tanaka’s lessons to Bond in “acting” Japanese in the way he moves and the way he regards others, including the passage cited above about not making way for women. Tanaka then points out how others react to him after this “transformation,” chiefly ignoring him rather than ogling the gaijin (foreigner), proving how well it worked.

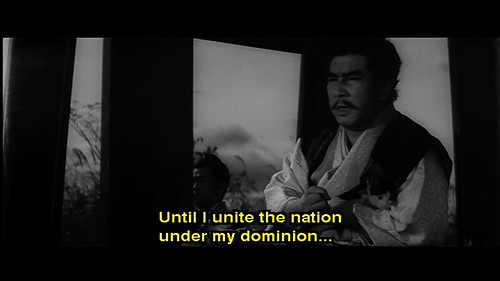

The mission in the book seems like more of an afterthought. The real point seems to be to thrash out notions about the war and U.S.-England-Japan relations. The book was written less than 20 years after the war and it includes numerous exchanges, between Bond and Dikko and between Bond and Tanaka, that illuminate English wartime and postwar attitudes towards Japan and, to a certain extent, Japanese attitudes toward the west. When Tanaka derides the British empire as “the pitiful ruins of a once-great power,” Bond offers a furious patriotic response. Tanaka describes why he became a kamikaze pilot and his lifelong regret at not dying that way. It’s rich material and the kind of thing that could never have made it into a Bond film, the formula of which precluded any actual insights into international relations or critiques of global powers and their post-colonial turmoil. There are numerous great quotes I’ve catalogued from the book, but I’ll try to find a couple of the most characteristic.

In one of Bond’s initial conferences over several bottles of sake with Dikko Henderson, the Austrialian explains the concept of obligation, or ON, in Japan and how anyone seeking anything from them has to do something to make the Japanese obligated to them. “All Japanese have permanent ON to their superiors, the Emperor, their ancestors and the Japanese gods,” he tells Bond. Bond responds by saying, “It doesn’t sound very demokorasu to me,” employing the Japanese version of the word, “democracy.” To which Henderson replies:

“Of course it isn’t, you dumb bastard, For God’s sake, get it into your head that the Japanese are a separate human species. They’ve only been operating as a civilized people, in the debased sense we talk about it in the west, for fifty, at the most a hundred years. Scratch a Russian and you’ll find a Tartar. Scratch a Japanese and you’ll find a samurai—or what he thinks is a samurai. Most of this samurai stuff is a myth, like the Wild West bunk the Americans are brought up on, or your knights in shining armour in King Arthur’s court. Just because people play baseball and wear bowler hats doesn’t mean they’re quote civilized unquote.”

In a scene in a private room in a geisha restaurant just before midnight, as Bond and Tanaka drink sake and Suntory, Bond asks Tanaka about his relations with the Americans, a necessary prelude to their negotiations over the sharing of intelligence. As part of my ongoing research into Japanese attitudes toward Americans, particularly during the postwar period, and as an American who’s had a lot of contact with the Japanese, I thought this lengthy quote, shortened from the original as it is, was worth including here. Tanaka launches into a summary, almost a tirade in fact, about the history of foreign settlers in Japan following the Meiji Restoration, leading up to his views on American settlers in Japan.

“…Now, since the occupation, there have been many such settlers, the great majority of whom, as you can imagine, have been American. The Oriental way of life is particularly attractive to the American who wishes to escape from a culture which, I am sure you will agree, has become, to say the least of it, more and more unattractive except to the lower graces of the human species to whom bad but plentiful food, shiny toys such as the automobile and the television, and the ‘quick buck,’ often dishonestly earned, or earned in exchange for minimal labour or skills, are the summum bonum, if you will allow the sentimental echo from my Oxford education….

“For the time being, we are being subjected to what I can best describe as the ‘Scuola di Coca-Cola.’ Baseball, amusement arcades, hot dogs, hideously large bosoms, neon lighting—these are the part of our payment for defeat in battle. They are the tepid tea of the way of life we know under the name of demokorasu. They are a frenzied denial of the official scapegoats for our defeat—a denial of the spirit of the samurai as expressed in the kami-kaze, a denial of our ancestors, a denial of our gods. They are a despicable way of life but fortunately they are also expendable and temporary. They have as much importance in the history of Japan as the life of a dragonfly.

“But to return to my story. Our American residents are of a sympathetic type on a low level of course. They enjoy the subservience, which I may say is only superficial, of our women. They enjoy the remaining strict patterns of our life—the symmetry, compared with the chaos that reigns in America. They enjoy our simplicity, with its underlying hint of deep meaning, as expressed for instance in the tea ceremony, flower arrangements, NO plays—none of which of course they understand. They also enjoy, because they have no ancestors and probably no family life worth speaking of, our veneration of the old and our worship of the past. For, in their impermanent world, they recognize these as permanent things just as, in their ignorant and childish way, they admire the fictions of the Wild West and other American myths that have become known to them, not through their education, of which they have none, but through television.”

Keep in mind, of course, that although a Japanese war veteran speaks these words in the book, they were put into his mouth by an Englishman and one who came from the upper class and served in Naval Intelligence during the war (Ian Fleming, pictured below).

In any event, the nature of the James Bond film genre, particularly as it had evolved by the fifth film, and international co-productions in general, meant that such monologues and idiosyncratic history lessons would only be found in the books.

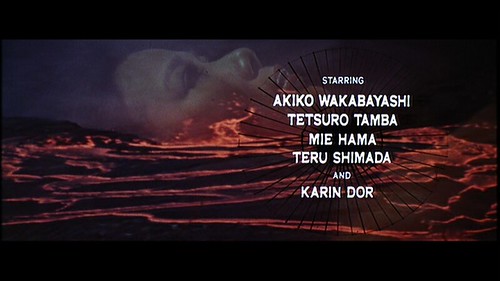

Getting back to the film, one of the aspects of it that most interested me was the casting of Japanese performers who were already well-known in Japan and had extensive credits, Wakabayashi, Tamba, and Hama. All were billed right after Sean Connery and before any other cast members, with Hollywood-based Japanese actor Teru Shimada listed on the same card with them, followed by German actress Karin Dor.

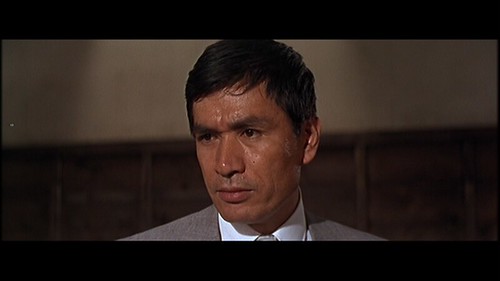

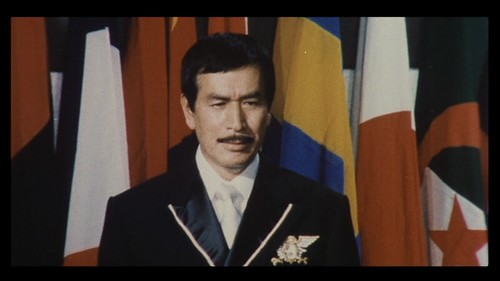

I would see each of the three Japanese performers in Japanese films in the years after seeing YOLT. Tetsuro Tamba had more of an international career than was common for a Japanese actor, so I saw him in other genres as well. He was in an Italian western called THE FIVE-MAN ARMY, just two years after this film. The next film I saw him in after YOLT was the Hong Kong swordplay epic, Chang Cheh’s SEVEN BLOWS OF THE DRAGON, a shortened version of THE WATER MARGIN (1972). One of Tamba’s samurai films, GOYOKIN, directed by Hideo Gosha, actually played in theaters in an English-dubbed version, retitled THE STEEL EDGE OF REVENGE, in late 1974. He’s also in Kinji Fukasaku’s MESSAGE FROM SPACE (1978), a Star Wars-inspired film which featured a mixed cast of American and Japanese actors and played in theaters in the U.S. and which I wrote about as part of my American Stars in Japanese Films series. I saw all of these films in theaters except for THE FIVE-MAN ARMY, which I eventually caught on television. Here is Tamba in MESSAGE FROM SPACE, where he played the President of the Earth Federation opposite American actor Vic Morrow:

The more I learned about the two actresses, Akiko Wakabayashi and Mie Hama, the more I realized that YOLT was not their first introduction to American audiences. The two of them had, in fact, been seen together in KING KONG VS. GODZILLA, which had been released in the U.S. by Universal Pictures in an English-dubbed, re-edited version in 1963, four years earlier than YOLT. Mie Hama was the Fay Wray of this version, getting plucked by Kong from a Tokyo train and carried by him to the not-very-imposing top of the Diet Building. Much of Wakabayashi’s footage was cut from the American re-edit, but one scene with them together remains intact as Wakabayashi brings bad news to Hama about her boyfriend, one of the film’s protagonists, found in a newspaper:

They were also together in two other films that had been shown in the U.S. prior to YOLT. SAMURAI PIRATE (1963), starring Toshiro Mifune, was released to U.S. theaters in a dubbed version as THE LOST WORLD OF SINBAD in March 1965. The two of them had also appeared in a spy film entitled KAGI NO KAGI (KEY OF KEYS, 1965), which would be taken by Woody Allen, working for American International Pictures, and re-dubbed with comical English dialogue and titled WHAT’S UP, TIGER LILY?, to be released in the U.S. on November 2, 1966. So that’s three films total that the two actresses appeared in together that had been available to U.S. audiences before YOLT. In addition, Akiko Wakabayashi had appeared in the Godzilla film, GHIDRAH, THE THREE-HEADED MONSTER (1964), which got released to theaters in the U.S. in an English-dubbed version on September 13, 1965. Wakabayashi also appeared in an episode of “Ultraman,” which ran on American television in 1966. She made only one film after YOLT and one TV appearance—a 1971 episode of an American show called “Shirley’s World,” starring Shirley MacLaine. She left the business after that. Mie Hama appeared in the samurai epic about the 47 Ronin, CHUSHINGURA (1962), which played in U.S. arthouses in 1963. Her next film after YOLT also got released in the U.S., KING KONG ESCAPES, in which she played a villainess, Madame Piranha. She has 15 credits after that, up to 1975, and then one credit in 1989. There was a recent interview with Ms. Hama earlier this year in The New York Times:

Teru Shimada, who plays Osato, the industrialist in league with SPECTRE, deserves special mention also. He had been working in Hollywood since 1932. I’ve written about him here in the past in connection with a Mr. Moto film in which he appeared (see Asian Detectives in Hollywood) and an episode of the western TV series, “Laramie” (see: Asian Stars in TV Westerns: Laramie). He has film credits from 1932 to 1941, after which he disappears from Hollywood, presumably sent off to a Japanese internment camp during the war, although IMDB lists a credit for him in 1944, playing a villager in the film, DRAGON SEED, which seems unlikely and I’d need to see the film to see if he’s visible before confirming. His credits pick up again at 1949 and continue steadily up to 1971, with one credit afterwards in 1975. His most active period is from 1956 to 1971, with many films and TV episodes. He was clearly the go-to Japanese actor in Hollywood when casting Japanese characters of a certain age and bearing.

One more film note should be made in regards to YOLT. The ninja lore depicted in the film owes some of its inspiration to an earlier Japanese film, SHINOBI NO MONO (1962), the first in a pioneering series of films about ninjas. The ninja advisor on that film, Masaaki Hatsumi, also served as the ninja advisor on YOLT. He even appears in one scene as Tanaka’s assistant, seen here on the left:

The earlier film had ninja training scenes that foreshadow the ones in YOLT.

It also had a villain, Nobunaga Oda, who, like Blofeld, strokes a cat repeatedly in the film.

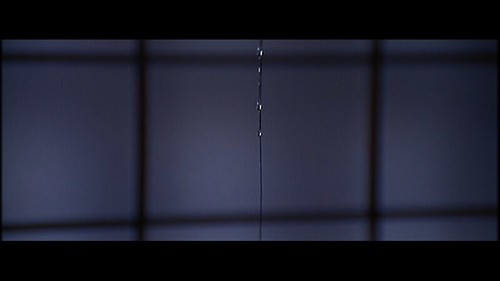

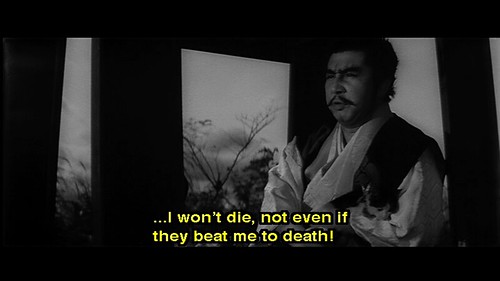

Also, the scene where a ninja poisons Oda using a string to allow the liquid poison to seep down into Oda’s mouth while he sleeps was recreated in YOLT where a ninja uses the same technique to try to poison Bond, but with tragic results for another character. Oda swallowed the poison but survived in the earlier film, thanks to his strong constitution and his resolve not to die until he had caused more mayhem and havoc.

Oda is played by Tomisaburo Wakayama, who would later star in the “Lone Wolf and Cub” film series (1972-74).

A lot of my favorite films had their initial release 50 years ago this year. THE DIRTY DOZEN, in fact, was released on June 15, 1967, two days after YOLT, and EL DORADO was released later in the month. I will do a Best of 1967 in a future entry, but I felt YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE deserved its own piece given the enduring impact it has had on me.

Great entry, Brian does it again. Full of filmic details and his personal obsessions.

I remember this detail from the novel (but don’t think it was in the flick – was it?):

Tiger Tanaka considers blowing one’s nose in a hanky and then putting said handkerchief back into one’s pocket to be disgusting. Instead, he used tissues and discarded them after nostril discharges. Do you remember this? Memory is funny – what we remember, what we forget…

Ian Fleming was not only a superb espionage novelist but also in the British tradition of travel writing set at exotic destinations, such as W. Somerset Maugham. (This is why in “From Russia With Love” aboard the train Bond and Tanya use the pseudonym of the “Somersets” – Fleming giving a tip of the hat to one of his masters.)

The real reason why Bond undergoes treatment in YOLT to “Japanese-ize” him is because this symbolizes the rite of passage of the Western male “going Native” in Third World “exotic” cultures. In the novel there was a long interlude where Bond moves with and becomes one with the rhythms of life amidst the female dominated pearl divers. It’s almost like South Seas cinema, which has some pearl diver-themed sagas. There, Bond returns to nature…

Brian used excellent visuals. Do you ever post links to clips from the flicks under the microscope? Writing online is for an audiovisual medium.

Believe it or not, as I conclude this e-pistle here in La La Land, on USC’s 91.5 FM classical station – and I swear to God this is true – “West Side Story” music is playing. I suppose an ode to Brian, who should make a book out of his insightful, amusing blog entries. BTW, noting that Bond was respectful in Turkey and Japan because they hadn’t been part of the British Empire is quite insightful!

. .

In his book James Bond in the Cinema, critic John Brosnan complained that YOLT is basically a bigger-budgeted remake of Dr. No, with SPECTRE sabotaging spacecraft from their island base, which Bond infiltrates and blows up.

Fleming actually wanted David Niven to play Bond, which may have something to do with his mention in the novel.

This was the first film in which Bond and Blofeld met face to face.

Karin Dor’s character seemed like an imitation of Fiona Volpe (Luciana Paluzzi) from the previous film, Thunderball. I suspect that if they had known how popular Fiona would be, they would have kept her on as a recurring villain, instead of killing her off in her first appearance.