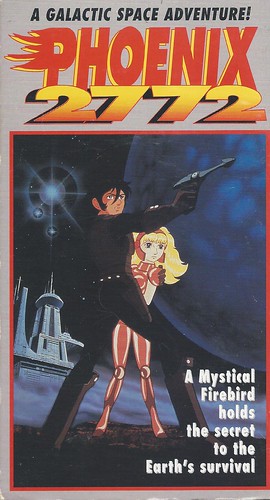

I had been following Japanese animation off and on from 1964, when I first saw “Astro Boy” and “Gigantor” on TV as a child, to the early 1980s when I saw the anime features PHOENIX 2772 and GALAXY EXPRESS 999 on the big screen, but it didn’t really take a permanent hold on my consciousness until the release of AKIRA in theaters in the U.S. in 1990 led to a trickle of Japanese animated features being shown at film festivals and repertory theaters.

I didn’t latch on to “anime” as a home video phenomenon until 1992, when I discovered a dealer’s table labeled Japanimation Video at a Star Trek Convention in midtown Manhattan. He was offering hundreds of Japanese animated films and TV shows on VHS tape, mostly in Japanese with no translation, having been transferred from Japanese laserdiscs to VHS, and I was hooked. After purchasing some titles from this dealer, I began scrutinizing shelves at local video stores, looking for legit anime releases, either English-dubbed or subtitled, as well as the local comics shows held once a month at midtown hotels to visit the Japanimation Video table, as well as other dealers. I also looked for magazines on the subject and began reading those. I slowly began building my collection.

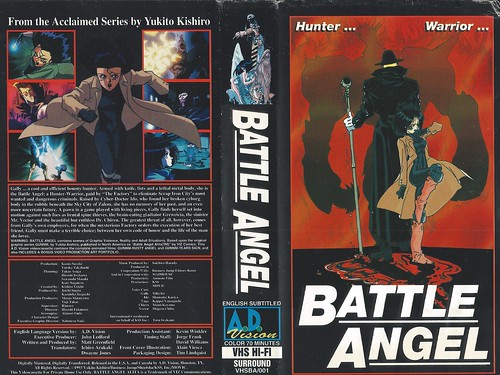

At the time, there were, as I recall, five anime distributors active in the United States. Streamline Pictures had the highest profile because it supplemented its home video releases with limited theatrical exhibition, including a handful of New York theaters, where I saw some of their films. The others were U.S. Renditions (which dissolved a few years later), A.D. Vision, AnimEigo, and U.S. Manga Corps (a division of Central Park Media), which followed Streamline’s example and also put some of its films into theaters.

According to Wikipedia, the first subtitled anime release on home video in the U.S. was GUNBUSTER and the second was DANGAIO, both from U.S. Renditions and both in 1990. I remember seeing ads for them on the back covers of fan magazines devoted to Japanese sci-fi films and TV shows.

I eventually acquired most of these tapes, but usually in used editions long after they first came out.

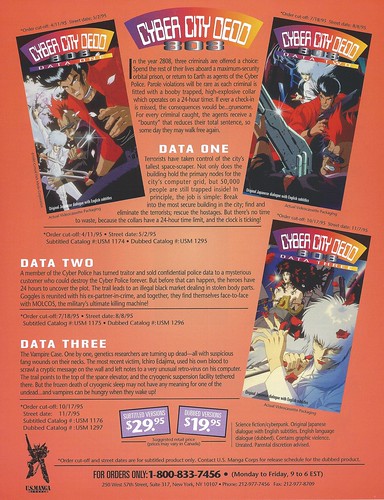

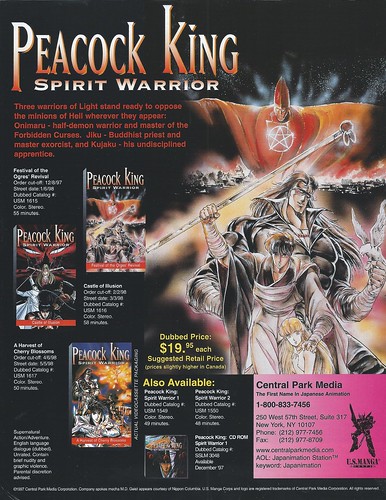

Some of the companies released their titles only in subtitled versions, some only English-dubbed, while others released them simultaneously in both dubbed and subbed versions, with the subbed versions going for higher prices. Notice the prices listed on this flyer:

The prices for these releases were generally pretty high, so most fans (including me) had to look for them at video rental outlets like Blockbuster and local mom-and-pop video stores. Look at the price, listed at the bottom, for one subtitled volume (about an hour long) of “Project A-ko”:

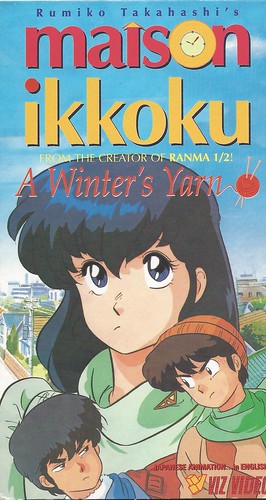

And look at the price sticker on this one. I paid considerably less because I bought it used:

I invariably preferred the subtitled version, but sometimes, much to my regret, I bought the cheaper dubbed version if that’s what I found first. (When anime came to dual-language track DVD in the 2000s, I upgraded many of these titles.)

Eventually, I began writing freelance anime reviews for different publications and wound up getting review copies of many titles, especially from U.S. Manga Corps.

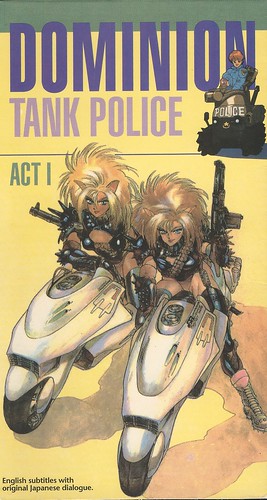

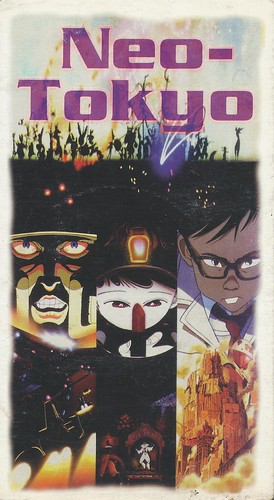

Most of the early anime video releases were science fiction action thrillers, many showing the influence, as did AKIRA, of Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER (1982). A lot of early enthusiasm for anime in the U.S. seemed to come out of the sprawling sci-fi fan community.

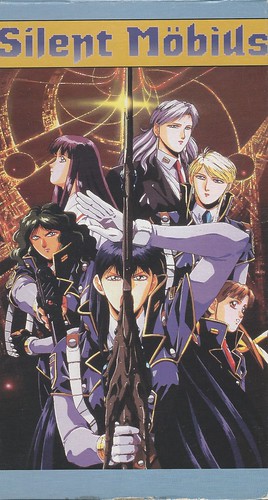

What strikes me as pretty obvious now, although I don’t recall how much comment it generated at the time, was the sheer number of female protagonists, often in groups, who dominated these productions. Women in cockpits or form-fitting battle suits were common images in anime releases of the time. In one extraordinary battle scene in “Iczer-One,” all the combatants were women. Other titles in this subgenre included “Gunbuster,” “Dangaio,” “Bubblegum Crisis,” “Gall Force,” “Sol Bianca,” and “Silent Mobius.”

Granted, of course, that some of these titles also had generous shots of the women disrobing, taking showers, donning sexy attire or, as in “Iczer-One,” piloting their combat vehicles in the nude(!), somewhat undercutting the feminist message with what came to be known as “fan service.”

What was also pretty obvious then, and quite frequently commented on, was the sheer prevalence of sex, nudity, violence, and graphic gore in some anime releases. These productions clearly weren’t meant for children and the distributors had to learn to emphasize this in their packaging or risk tirades from angry parents whose kids had rented “Japanese cartoons.” There was even a Japanese word for the most extreme examples of this sub-genre of anime, a term picked up and used by American fans: hentai.

Some of these were shown in theaters as well. I saw both LEGEND OF THE OVERFIEND (which would certainly have gotten an “X” rating if submitted to the MPAA) and WICKED CITY, which had graphic sex and rape-by-demon scenes, in theaters in 1993.

Another common element of early anime releases in the U.S. was “mecha,” a term for elaborate mobile combat machines, normally operated by a single pilot inside the cockpit, engaged in battle with opponents piloting similar machines. There was usually a lot of collateral damage wherever the clashing metal fights took place, with plenty of explosions, rocket blasts and buildings falling. The animation in such scenes was often quite intricate, with many different parts of the machines in motion in any given shot, creating spectacular results in spite of the minimal budgets accorded TV and made-for-video animation. (Dialogue scenes, however, were often quite static, so they saved money that way.)

The home video releases of the time included theatrical feature films and TV episodes, but were mostly made-for-home-video animated productions called OAV (Original Animated Video) or OVA (Original Video Animation). These were released directly to video stores on VHS tape and, later, laserdisc. OAV episodes could be single stand-alone stories or part of longer series that lasted anywhere from two to 13 episodes, although some went on much longer. Single episodes were usually just under an hour, although they could be as short as 24 minutes and as long as 90 minutes. Since they didn’t have to conform to a specific time slot or be submitted to TV censors, the makers of OAVs had pretty much free reign in the length of their stories and the maturity of their subject matter. It was also common for long-running anime TV series like “Urusei Yatsura” to spin off side stories as OAVs.

Among the OAV series released to home video in the U.S. during this period were the aforementioned “Gunbuster,” “Dangaio,” “Bubblegum Crisis,” and “Dominion Tank Police.”

The very first OAV series in Japan was “Dallos” (1983), a four-part story directed by Mamoru Oshii (GHOST IN THE SHELL), about civil conflict at an Earth colony on the moon. The four parts were edited together, with significant cuts, and released as a single feature-length 83-minute movie, dubbed in English, on home video in the U.S. by Best Film & Video Corp. (The uncut “Dallos” ran 120 minutes in total.)

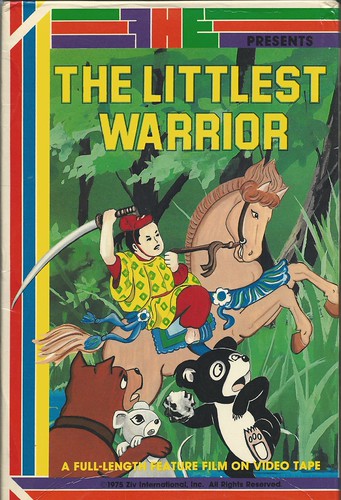

I should point out here that Best Film & Video Corp. released quite a number of Japanese animated features on tape in English-dubbed versions edited extensively for content, since they were aiming them at the children’s market. A number of companies like this were active in the 1980s, well before the anime boom, acquiring Japanese animated productions, both feature films and TV episodes, dubbing them into English and packaging them as family entertainment in a way that hid or downplayed the Japanese origins. I found tons of these tapes in used video bins throughout the 1990s. This would make an interesting chapter in the history of Japanese animation’s reception in the U.S., but I’ll save it for a future entry. In the meantime, here’s a video case and representative shots from tapes of that era, THE LITTLEST WARRIOR, THE LITTLE MERMAID and LITTLE WOMEN:

I previously wrote about THE LITTLE MERMAID here.

Getting back to the 1990s, other OAV titles found among early home video anime releases in the U.S. were “Raven Tengu Kabuto” (1992, from L.A. Hero), a period ninja adventure tale with some sci-fi touches; “Battle Angel” (1993, A.D. Vision), about a female cyborg bounty hunter brought back to “life” by a compassionate scientist (and the basis for the 2019 Hollywood release, ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL); and “Fight! Iczer-One” (1985, U.S. Renditions), about an alien female space fighter who comes to Earth to block an invasion.

“Crying Freeman” (1988-1993) was an OAV crime series about a Japanese hitman forced to work for an ancient society of Chinese assassins and was released by Streamline Pictures, dubbed in English. It would be several years before the six-part series was released in Japanese with English subs by a different company (ADV). It was based on a manga written by Kazuo Koike, about whom I wrote here.

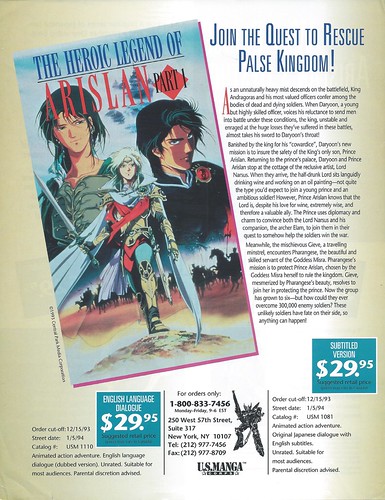

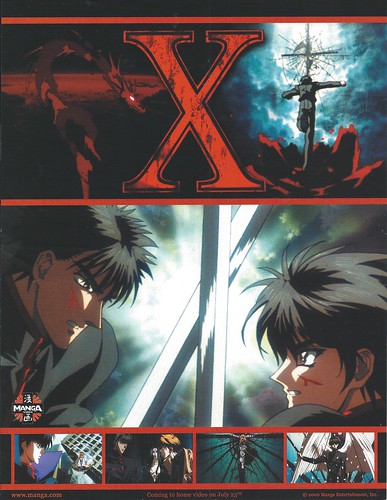

By the mid-’90s, many more OAV productions hit the U.S. market, as seen in these flyers from different anime distributors:

I soon discovered a wider array of anime stories and genres than just the sci-fi action pieces. The Tale of Genji (1987), from Central Park Media, offered a beautifully designed feature-length adaptation of Japan’s oldest and most revered literary text.

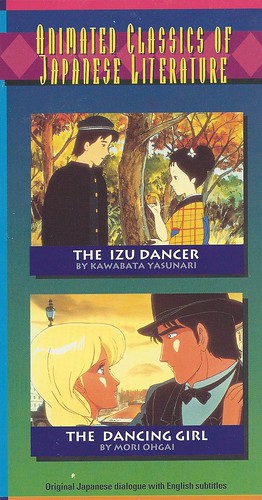

Animated Classics of Japanese Literature (1986), from Central Park Media, was a TV series that did half-hour adaptations of Japanese literary works, either short stories or novels, with some stories being told in multiple episodes.

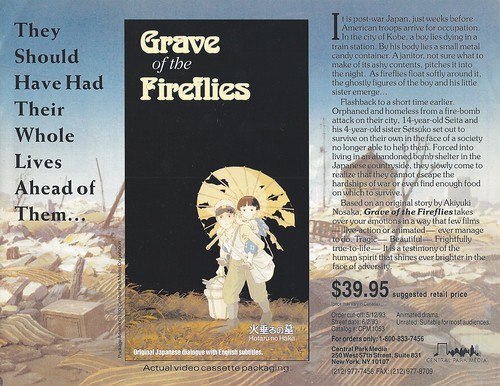

Grave of the Fireflies (1988), from Central Park Media and directed by Isao Takahata, was a theatrical feature chronicling the tragic story of an adolescent boy and his little sister, orphaned during the final months of World War II, who wind up having to fend for themselves in the Japanese countryside.

Vampire Princess Miyu (1988-89), from AnimEigo, was a four-part OAV series about a cute little vampire girl who fights demons who possess citizens, including her middle-school classmates, in contemporary Japan. It was done in a heightened artistic style based on classical Japanese art and design.

The Heroic Legend of Arslan (1991-93), from U. S. Manga Corps, was an OAV series that told a story of historical adventure and a young man’s battle for the throne in an ancient region patterned after Persia.

Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s “Ninja Scroll” (1994), from Manga Entertainment, told a bloody tale of a pair of ninjas, one male and one female, who take on political corruption in old Japan and confront a formidable crew of mystical foes known as the Eight Devils of Kimon.

Comic fantasies by female manga artist Rumiko Takahashi were turned into two long-running TV series in Japan. Viz Video distributed Ranma ½ (1989-92), which centers on a teenaged martial artist who falls victim to an ancient Chinese spell that turns him into a girl when doused with cold water.

AnimEigo distributed Urusei Yatsura (1981-86, aka “Those Obnoxious Aliens”), also by Takahashi, a TV series about a hapless, girl-obsessed teen boy who acquires a sexy, super-powered alien wife named Lum, who moves into his household and tries to block his girl-chasing.

Pioneer gave us “Tenchi Muyo!” (1992-93), an OAV series that offered comic adventures involving a Japanese teenage boy, the heir of an ancient family of shamans, who becomes involved with a host of alien women visiting Earth who all attach themselves to him.

Early promotional literature still clung to the term “Japanimation.” Only gradually did “anime” become the accepted term for Japanese animation. This ad from U.S. Manga Corps finally stresses “anime” and even tells us how to pronounce it.

The chief draw of anime for me wasn’t just the storylines aimed at a more adult audience, but the intricate artwork and design. It was the graphic originality that caught my eye, the way the characters were drawn, the way their faces and eyes conveyed emotion, the way they moved; the detail of the landscapes, whether historical settings from the past, gleaming high-tech cities, dystopian urban districts, or desolated post-apocalyptic landscapes. Whole worlds were created that we, the viewers, wanted to explore. Sure, there were frequent infusions of sex, violence, bloodshed and horrific monsters with gaping mouths, long sharp teeth, claws and various appendages, but this was all rendered in provocative and imaginative ways and with great attention to gruesome detail. I reveled in the dramatic, often surreal imagery. And best of all, everything was executed in pen and ink on individual cells photographed under hot lights on 35mm motion picture film and transferred to video. Pure analog works of art. (Of course, I have to admit that unless one has access to film prints, these works are best watched today on digital formats like DVD and Blu-ray.)

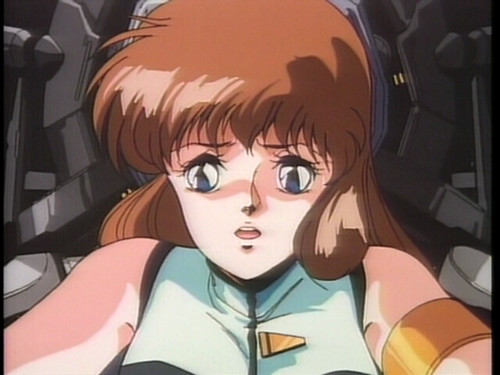

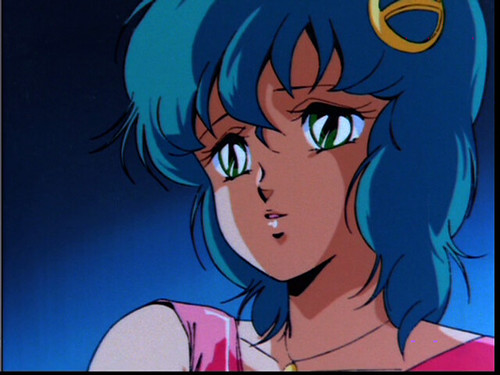

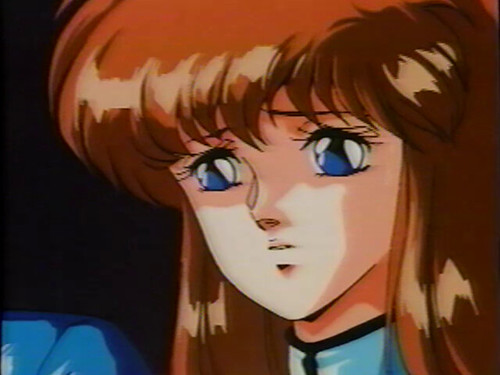

There was a powerful, often melancholy emotional tone that set these works apart from American animation. The characters’ feelings were revealed in frequent closeups, with emotions often shifting subtly in the course of a scene, thanks to the large shape of the eyes and some expert linework, as seen in these closeups of Miya Alice, one of the trio of pilots from “Dangaio”:

In “Fight! Iczer-One,” which I re-watched for this piece, the villainess Sepia grieves when her female partner (and lover) Cobalt is killed in combat with the title heroine, Iczer-One, and her human partner, Nagisa. It’s quite an effective scene and lets us know what’s at stake in the battles to come. The villains are not just monsters. They’re human as well.

As the ’90s wore on, more and more fans, looking for something new, original, and stimulating, discovered anime. Many more great films and series were imported to fill up the shelves of the growing anime sections of our local video stores, in addition to those already cited above. Every company contributed, including U.S. Manga Corps, Viz Video, AnimEigo, Pioneer, ADV Films and the newer companies, Manga Entertainment and The Right Stuf.

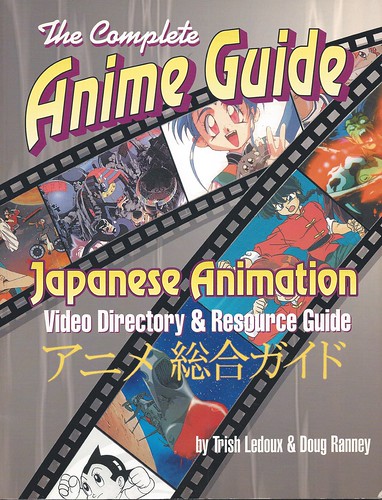

A helpful book was published in 1995, listing all anime releases in the U.S. up to that point, and an update was published two years later.

And I haven’t even mentioned Hayao Miyazaki. Only one of his features actually got distributed legally in the U.S. on home video for most of the 1990s, and only in an English-dubbed version:

That would change in 1998, when KIKI’S DELIVERY SERVICE got its first U.S. home video release.

However, both MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO (1988) and Miyazaki’s first feature, THE CASTLE OF CAGLIOSTRO (1979), a spin-off of the Lupin III TV series, played in theaters in New York in the early 1990s. I took my daughter to see CAGLIOSTRO in 1992 and TOTORO in 1993.

To give you another idea of the anime landscape at the time, here are the first two trailers U.S. Manga Corps used to promote their anime lineups. The first, dating from 1993-94, offers only eight titles. The second, from a year later, offers 14.

If all this has inspired you to explore anime more, please consult the book I co-authored with Julie Davis, former editor of Animerica, Anime Classics Zettai: 100 Must-See Japanese Animation Masterpieces, from Stone Bridge Press.

Update: On October 28, 2021, I did a manga counterpart of this piece, Japanese Comics: Discovering Manga in the 1990s: https://briandanacamp.wordpress.com/2021/10/28/japanese-comics-discovering-manga-in-the-1990s/ If you enjoyed the above, you might enjoy this one, too.

This was an amazing and very enjoyable read.

I completely agree!

Funny I wasn’t aware of real anime until I went to blockbuster in maybe 1995 to rent a Pokemon VHS from the series (which was currently airing season 1 on television) but there wasn’t any copies left for it so instead I rented something else at the age of 12.

Which was on the same anime shelf with few others so I went with it.

Later I found it very strange with a teen in a costume of the white rabbit from alice in wonderland an a big clock maybe which could have been some portal and it was not dubbed it was subbed and with yellow subtitles too!

Looked like it was the start of a fantasy with quite a bit of comedy with a female character with a really bad temper especially after this guy said her name then the word for a female dog lolI sure I wanted to see more of it in my later teenage years but I don’t remember anything more about it .

Do you know what it was ? Must have been something really obscure (I tried to find anything on it online again in my adult years and thats how found this great article down memory lane for all the retro anime I seen which were rated mature on the now sadly dead Starz channel the Action Channel which was my much deeper step into adult anime at maybe 14 years of age.

this wonderful article for 80-90s japanimation a.ka. anime..

help me to pick back all nostalgic dub anime

great job man.