Sam Peckinpah’s provocative western, THE WILD BUNCH, opened in the U.S. on June 25, 1969, 50 years ago this month. I’ve seen the film many times over the years, including at least 20 times on the big screen and multiple times in a variety of formats: broadcast TV, VHS, DVD and Blu-ray. It was a sprawling epic western full of action, gunplay and bloodshed, rated R and featuring a predominantly male cast of Hollywood stars, dependable character actors, a couple of newcomers, and veteran Mexican performers, but only a handful of women with small speaking parts (mostly as prostitutes). The stars were William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, Edmond O’Brien, Warren Oates, Ben Johnson, Jaime Sanchez, Strother Martin, L.Q. Jones, and Emilio Fernandez. In the leadup to the film’s release, I saw all the print ads—in newspapers and on the subway–with lines like, “Nine men who came too late and stayed too long.” I read all the pre-release articles and finally the reviews–the negative ones which criticized the blood-spurting and called William Holden “dissipated” and the positive ones like Vincent Canby’s in The New York Times who ranked it way above the other big westerns of that season, TRUE GRIT and BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID. Sergio Leone’s ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST also opened that summer, a week after THE WILD BUNCH.

I first saw the film in the late summer of 1969 when it had finally arrived in the Bronx—after I’d seen TRUE GRIT and ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST, but before I’d seen BUTCH CASSIDY. I’ve seen all four of these westerns multiple times, but it was THE WILD BUNCH that I grew most obsessed with and went back to over and over again. I found a few pieces I’ve written about the movie in my files that were never published anywhere, so I thought I’d use them here to try to explain that obsession.

This first section is from the same proposed book on 42nd Street movies that I excerpted from in my previous blog post, Filming Across Cultures: Cowboys, Samurai and Kung Fu Champs. I talk about why THE WILD BUNCH resonated so strongly with audiences of the time and I stress its connection to an earlier film with similar themes, Robert Aldrich’s VERA CRUZ (1954).

In 1969, Sam Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH expanded on the theme of outcasts on a doomed mission with its story of aging American outlaws who flee to Mexico for one last score. Set during the Mexican Revolution of 1913, it paid lip service to issues of third world revolution and put its protagonists in the position of robbing U.S. army guns for a brutal general, Mapache (Emilio Fernandez), who exploits, oppresses and murders the rural villagers of Mexico. When the outlaws finally turn against their employer and go down fighting in a spectacular blaze of glory, they do it more for personal reasons–to rescue their Mexican partner Angel (Jaime Sanchez)–than to save the people of Mexico, but the justness of their actions and the nobility of their self-sacrifice were not lost on an audience that was watching American soldiers burn down Vietnamese villages on television.

Controversial at the time and hotly debated, the film’s use of spurting blood from bullet holes and slow motion slaughter in the film’s major gun battles raised the violence quotient in Hollywood westerns to that of Japanese samurai films and Italian westerns. Art critic Lawrence Alloway recognized this connection and was the first to explicitly link Kurosawa, Leone, and Peckinpah in “Violent America: the Movies 1946-1964” (Museum of Modern Art, 1971):

“The Westerns made by Sergio Leone in Italy from 1964 revived the genre by the new magnitude of slaughter. Based on a mastery of the American Western, he expanded action to the high pitch of violence characteristic of Japanese Samurai films. The original The Seven Samurai, 1954, directed by Akira Kurosawa, was remade by John Sturges in Hollywood as The Magnificent Seven, 1960, but Sturges failed to catch the cruel edge of Kurosawa. Leone, however, succeeded in uniting the two forms. Only after this was Samuel Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, 1969, able to cope with violence of Italo-Japanese intensity.”

Like Kurosawa and Leone, Peckinpah boasted an original and innovative visual style which found exciting new ways to depict scenes of violent combat. Shooting on location in Mexico, Peckinpah made creative use of telephoto and zoom lenses, slow motion, and montage editing and, with cameraman Lucien Ballard, fashioned a brown, sun-baked period look which evoked 1913 war-torn Mexico as no other western had ever done.

THE WILD BUNCH appealed to minority audiences, discontented young adults, and older men who were somewhat frustrated and angered by the general tone of the times. For teens like myself at the time, the characters in the film, played by actors from our fathers’ generation–William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Edmond O’Brien, Robert Ryan—reminded us of our fathers. They hadn’t achieved their dreams or ambitions, they spent a lot of time drinking, and were disillusioned with society. As outlaw Pike Bishop (Holden) tells his Mexican employers in the film, “We share few sentiments with our government,” which drew applause and roars of approval from Vietnam-era audiences. There were frequent debates in the film about code, including this celebrated exchange between Pike and his partner Dutch (Borgnine) over onetime Bunch member Deke Thornton’s (Ryan) dogged pursuit of them with a band of bounty hunters despite his one-time closeness to Pike:

Pike: “He gave his word.”

Dutch (disparagingly): “To a railroad.”

Pike: “It’s his word!”

Dutch: “It doesn’t matter! It’s who you give it to!”

This was, for many of us, the first American film to give a detailed background of a third world revolution. After seeing the movie, I spent a lot of time at the library looking up the Mexican Revolution and wound up devoting my high school world history term paper to the subject. At the time, the Mexican Revolution was a popular choice of background for many westerns, both American and Italian, because it allowed for American stars (as mercenaries on either side), modern automatic weaponry, and automobiles, trucks and airplanes, while still relying on frequent shots of armed men in western dress riding around dusty landscapes on fast horses. The setting offered the opportunity for large-scale battle scenes that would have been out of place in traditional westerns and allowed for the slaughter of hundreds of uniformed soldiers by bandits, rebels, or American outlaws. In addition, themes of imperialism, foreign intervention and resistance by third world peoples were all increasingly fashionable at the time with a growing politicized audience and were quick to be exploited by Italian filmmakers in such westerns as Damiano Damiani’s A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL and Sergio Sollima’s FACE TO FACE.

There’s an important connection here to an early film by one of the auteur directors who was popular among action fans at this time. Robert Aldrich’s VERA CRUZ (1954) was also set during the Mexican Revolution, albeit an earlier one involving Juarez and the Emperor Maximilian and set just after the Civil War. It involved American drifters, led by Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster, who go to work for Maximilian, but wind up joining the revolutionaries and going down in a blaze of fighting (excepting Cooper, of course). It had a minority character, a black union veteran played by Archie Savage. It had future Wild Bunch member Ernest Borgnine and future Magnificent Seven member and Leone star Charles Bronson. (Both Borgnine and Bronson were also in Aldrich’s THE DIRTY DOZEN, 1967). And it had Jack Elam, who would appear with Bronson in Leone’s ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST (1969).

Below, L-R: Jack Elam, Ernest Borgnine, Charles Bronson, Archie Savage:

There were several scenes that had direct counterparts in Peckinpah’s film, including a scene of the Americans relaxing and partying in a Mexican village while en route to their destination. Issues of code figured heavily among its amoral characters, with both Cooper and Lancaster planning to steal the gold shipment accompanying the countess they’ve been hired to protect, but splitting over the issue of how to dispose of the gold, Cooper having been won over to the revolutionaries’ cause, Lancaster out to keep it all for himself.

VERA CRUZ also links Aldrich to both Leone and Kurosawa. Its visual style foreshadows Leone’s films, particularly in the final gun duel between Cooper and Lancaster which offers a tighter, more compact version of the extended showdowns which close Leone’s westerns.

Aldrich’s use of extreme angles, mixing long shots and closeups, and emphasis on music all clearly influenced Leone (who worked with Aldrich during the Italian shooting of SODOM AND GOMORRAH in 1962). VERA CRUZ was made the same year as Kurosawa’s THE SEVEN SAMURAI and both films established the tradition of male camaraderie involving groups of drifters, skilled in the fighting arts, who band together, for a fee, and wind up sacrificing themselves for a cause.

When we see the influence these films had on their successors, it becomes clear that there is a connection between the action filmmaking traditions of three continents and a thread that stretches from VERA CRUZ and THE SEVEN SAMURAI (both 1954) through THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN (1960) and YOJIMBO (1961), to the Italian spectacles (which included GLADIATORS SEVEN, a variation of the “seven” theme); the James Bond films, particularly YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE, with their mixture of western and eastern fighting motifs; the Leone films and other Italian westerns; the later action films of Peckinpah and Aldrich; Jean-Pierre Melville’s LE SAMOURAI; and the Hong Kong kung fu and Japanese samurai films of the 1970s. I would even include some of the Hollywood police thrillers, such as Don Siegel’s DIRTY HARRY, whose title character was basically Yojimbo reined in by a municipal bureaucracy. The thread extends of course back to the hard-boiled American fiction of the 1920s and ’30s by Dashiell Hammett (whose “Red Harvest” was the source for YOJIMBO), W. R. Burnett, and Raymond Chandler and the early films based on their novels and similar works, including THE MALTESE FALCON, HIGH SIERRA, THIS GUN FOR HIRE and THE BIG SLEEP, which take us full circle back to James Agee’s pro-noir reviews and Manny Farber’s “underground films.” Nearly all of these films played 42nd Street and Times Square theaters.

This following piece is a post I did in 2005 for the Mobius Home Video Forum. It was part of a larger discussion about THE WILD BUNCH:

I turned 16 the summer that THE WILD BUNCH, Sam Peckinpah’s violent epic western about American outlaws embroiled in the Mexican Revolution, came out in theaters. Because of the film’s notorious reputation, based on its then-new depiction of spurting blood from gunshots, my father berated me for seeing it and never went to see it himself. It was a film I kept going back to, thanks to Warner Bros., which kept sending it out on double and triple features in the early 1970s enabling me to see it on the big screen at least 15 times back then. It also played at repertory houses throughout the early ’70s and would attract an audience that also kept going back to it. This was a crowd, mostly men my age or older (although I once took my then-15-year-old sister to an all-night Peckinpah show at which it played), with whom the film resonated powerfully. This crowd would give out almost primal reactions to certain things in the film, including a particular action that comes late in the film at the very start of the climactic battle between the Bunch and the Mexican army. After shooting General Mapache dead, and freaking out the drunken soldiers sprawled around the plaza, Pike Bishop (William Holden) aims his .45 automatic at Mapache’s German military advisor, Mohr (Fernando Wagner), setting off a gleeful anticipation of what came next among an audience that was already intensely familiar with the film. Holden then shoots the German and the crowd would whoop and applaud.

It wasn’t until the 25th anniversary screening of this film in 1994 that it dawned on me what was going on here. The lead actors in the film (William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, Ben Johnson, Edmond O’Brien) were members of my father’s generation. One of these actors, in fact, always reminded me of my father—Edmond O’Brien (but not the way he looks in this film!). The characters they played—drinkers and failures–also reminded me of my father and I think they touched a chord with many in the audience who were looking for some kind of connection with their emotionally distant fathers or their fathers’ experiences that they weren’t able to get at home. Certainly Pike Bishop, Holden’s character—leaving aside his criminal behavior and callous disregard for innocent lives—was someone who once had grand dreams and great hopes for the future, but by 1913 is just an aging, alcoholic bandit with gnawing wounds, both psychological and physical, and only a vain hope of making that one final score on which he can retire. On some level, he shared a certain emotional state with a lot of WWII veterans who’d come out of the war with dreams, talents and hopes (as my father had) and wondered, 25 years later, over a bottle of booze, what the hell had happened to it all.

The shooting of the German officer served as an emotional flashpoint for the older baby boomers in the audience who’d grown up in the shadow of World War II and had been immersed in the emotions of that war from childhood. There was an almost palpable current running through the audience at this point, wanting to shout “Kill the kraut!” but not needing to, because we knew it was going to happen. Of course, at the 25th anniversary screening, no one cheered when the German was shot, either because the audience was that much younger and had no idea that such a gesture had any larger significance outside the film or the WILD BUNCH regulars in attendance, if any, had mellowed somewhat.

Back to 2019. I’d like to share one memory from that very first screening in the Bronx in 1969. I don’t know whether you’ll find this hilarious or horrifying, but there was a young couple sitting behind me with their daughter who must have been around four years old, way too young for a film like this. The only utterance I heard from her through the entire film was when she saw this shot of Ernest Borgnine and shouted out with glee, “McHale’s Navy!”

I’d like to add that the last time I saw the film was in 2014 on Blu-ray. The last previous time I’d seen it was a few years earlier on a VHS tape, which I’d pulled off the shelf on a whim because it was handier than the DVD. That VHS screening was also the last time I enjoyed the film. Watching it on Blu-ray, I found myself strangely dissatisified. Had I seen it too many times (close to 30)? Was the violence just too gratuitous for my tastes now? Or maybe there was something wrong with the Blu-ray. I’ve had that experience before with Blu-rays where I felt something was off. Maybe a battered 35mm print at a neighborhood theater was, after all, the best way to experience this film.

As of this writing, the only cast members with major speaking parts who are still alive are Jaime Sanchez (Angel), L.Q. Jones (T.C.), and Alfonso Arau (Herrera).

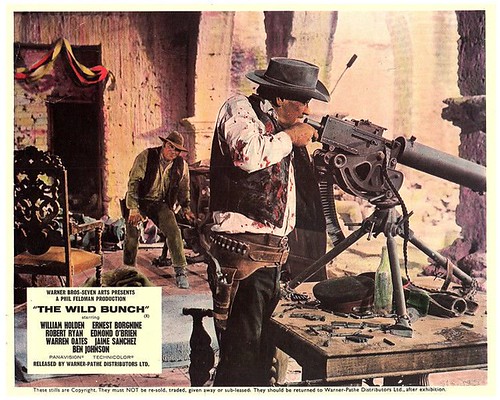

Finally, here is a gallery of images from the film, along with some of the most memorable lines:

Pike Bishop (William Holden): “Come on, you lazy bastard!”

Crazy Lee (Bo Hopkins): “Well, how’d you like to kiss my sister’s black cat’s ass?”

Coffer (Strother Martin) to T.C. (L.Q. Jones): “C’mon, T.C., help me git his boots!”

Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan): “How does it feel to be so Goddamned right?”

Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine): “I think the boys are right. I’d like to say a few words for the dear, dead departed. And maybe a few hymns’d be in order. Followed by a church supper. With a choir!”

Sykes (Edmond O’Brien): “Caught you, didn’t they? Tied a tin can to your tail. Led you in and waltzed you out again. Oh my, what a bunch! Big tough ones, huh? Here you are with a handful of holes, a thumb up your ass, and a big grin to pass the time of day with.”

Angel (Jaime Sanchez): “Mexico lindo.” Lyle Gorch (Warren Oates): “I don’t see nothin’ so lindo about it.” Tector Gorch (Ben Johnson): “Just looks like more Texas as far as I’m concerned.”

Pike Bishop: “When you side with a man, you stay with him! And if you can’t do that, you’re like some animal, you’re finished!”

Don Jose (Chano Urueta): “We all dream of being a child again, even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all.”

Lyle: “Just look at her lickin’ inside that Heneral‘s ear.”

Lyle: “Boys, I want you to meet my fiancée.”

Angel: “Just do your work.”

Pike: “Any trouble, no guns for the General.”

Herrera (Alfonso Arau): “That’s very smart for you, damn gringos!”

Pike: “Let’s go.”

Lyle: “Why not.”

Pike: “Come on, you lazy bastard.”

Sykes: “Well, me and the boys got some work to do. You want to come with us? It ain’t like it used to be, but it’ll do.”

To “Vera Cruz” which opened the final chapter, and to the “The Wild Bunch” and “Once Upon a Time in the West”, which closed it all so perfectly. End of story.

“Let’s go.” “Why not.”