As film buffs everywhere, led by TCM, celebrate the 100th anniversary of the merger that formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer on April 17, 1924, and recite the litany of great films from the Golden Age of that studio from the 1920s to the early ’50s and the roster declaring “more stars than there are in heaven,” I thought it might be useful to recall some of the films that came later in the studio’s history, particularly in the troubled days of the 1960s and ’70s when turbulence in the executive suites led to the studio’s decline and the destruction of its fabled backlot. I experienced this period in real time, particularly from 1969 on, and remember reading trade paper accounts of the controversial actions of new studio owner Kirk Kerkorian and production head James T. Aubrey, who was there a short time (1969-1973), but managed to burn a lot of bridges during his tenure. Yet I continued to see MGM releases during this period, including a few of my favorite films from the studio, most of which marked quite a contrast with the Golden Age MGM classics which remain beloved by millions today (including me). I’ll start with the earliest MGM films I saw as a young moviegoer. This won’t be a comprehensive account of this era of MGM’s history, just the highlights, including some I saw in theaters and some I discovered years later, usually on TCM.

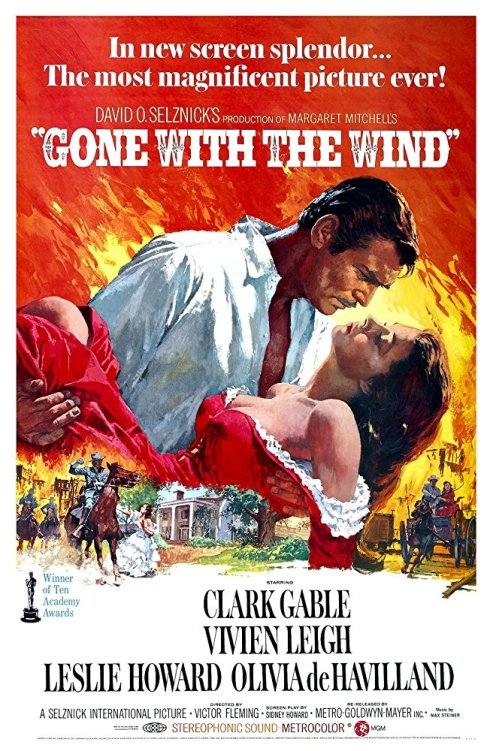

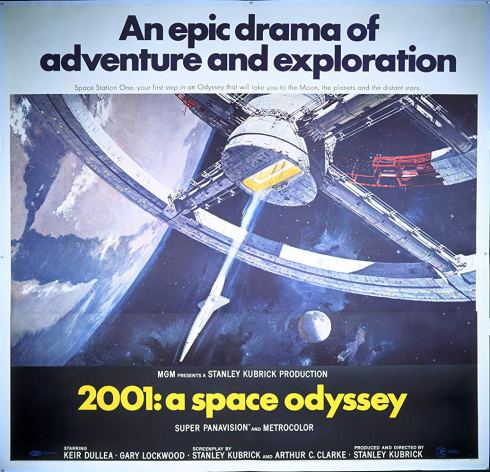

From 1960-69, I saw 25 MGM films in theaters, including such big-ticket items as BEN-HUR, THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN, THE TIME MACHINE, MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY, HOW THE WEST WAS WON, DR. ZHIVAGO, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, and a highly-touted re-release of GONE WITH THE WIND. (BEN-HUR, HUCKLEBERRY FINN and MUTINY were actually remakes of much earlier MGM films.) Usually it took these films a while to reach neighborhood theaters after their initial Broadway showings, at least two years in the case of BEN-HUR (1959). I was lucky enough to see HOW THE WEST WAS WON (1962) in Cinerama at a Broadway theater on a 4th Grade class trip. I remember looking up and checking out the three projection booths employed for the Cinerama process. Our teacher purchased the program book for the film and placed it in the class library and I devoured it during recess hours, learning the names of all the actors in it.

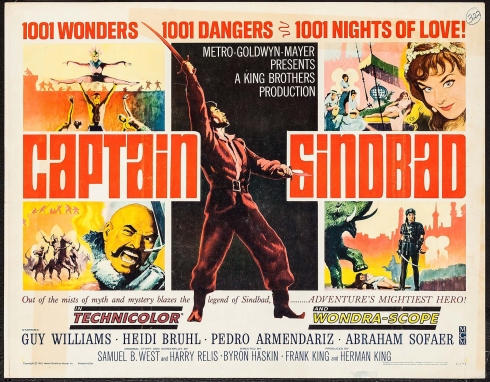

However, one of the films I remember most fondly from this early period was a fantasy adventure made in Germany by the King Bros., a pair of veteran low-budget producers, and released by MGM, CAPTAIN SINDBAD (1963), which I watched again for this piece. It’s filled with sorcery, monsters, swordfights, perilous adventures, beautiful women, and lively antics from a partly American, partly German cast who seem to be having the time of their lives. While the effects vary from crude to barely passable by modern standards (one of the monsters Sindbad fights is even invisible!), they were much appreciated at the time and are done with imagination, wit and great frequency. As a child I had no complaints. Sindbad is played by Guy Williams, the star of Disney’s “Zorro” TV show, and he tackles the part with verve and enthusiasm. Pedro Armendariz, who made this right before his very last film, FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE (1963), plays El Kerim, a tyrant who steals the wizard’s magic ring, deposes the rightful king, abducts the king’s daughter, Princess Jana, who happens to be Sindbad’s intended bride, and wreaks all sorts of havoc before Sindbad is able to climb the massive rope in a high bell tower and find and destroy El Kerim’s wicked heart, kept there for safekeeping. Armendariz plays the part with relish and never once reveals the illness which ended his life just before the film’s release.

CAPTAIN SINDBAD occupied the second half of a double bill with another MGM film, which I remember being pretty funny:

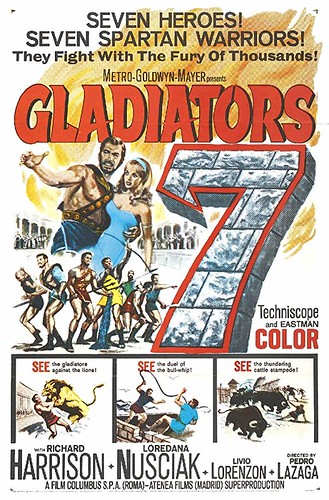

It was a common practice in the 1960s for studios to fill the gaps in their shrinking production schedules by importing foreign genre films for English-dubbed release in the U.S., including some great peplum from Italy. MGM released one I saw in a theater, GLADIATORS SEVEN (1966), which ran on a bill with a reissue of WEST SIDE STORY and a package of vintage Three Stooges shorts, playing to a packed audience on a summer afternoon. A sword & sandal take-off on THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, it starred American actor Richard Harrison, who left a marginal career in Hollywood to star in Italian action films (and, later, Hong Kong kung fu films) for the next 20 years. (This triple feature was the last time I attended the Tremont, the theater closest to my home. It shut down for good not long after that.)

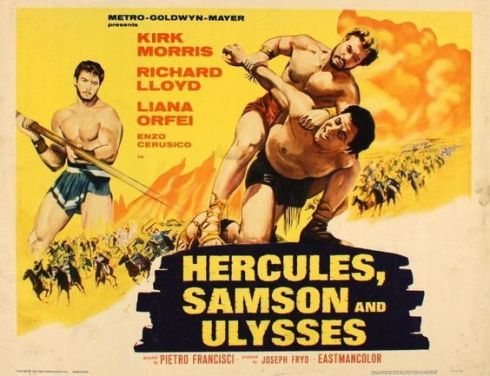

Another MGM pickup of this type, which I first saw on late-night broadcast TV, was HERCULES, SAMSON AND ULYSSES (1963). Here’s a brief note from my revisit to the film when it played on TCM in 2019: “This is actually pretty damned good. It has a real budget, with a couple of full-size ships and location shooting somewhere and some big sets, including a palace exterior that looks real. I love the scene where Hercules and Samson get into a big fight amidst what looks to be actual ancient temple ruins, but are soon revealed to be massive props that the actors start knocking down in the course of their battle.”

One of the most unusual pickups by MGM during this period was the Japanese animated feature, SHONEN SARUTOBI SASUKE (1959), only the second color animated feature released by Toei Animation, dubbed in English and given the title, MAGIC BOY. This made MGM the first major studio to release a Japanese animated feature in the U.S., a feat that wouldn’t be duplicated until Warner Bros. released POKÉMON THE FIRST MOVIE – MEWTWO STRIKES BACK in 1999. MAGIC BOY was not given a wide release, though, and I didn’t see it for the first time until TCM ran it decades later. (It has since come out on DVD from Warner Archive.) According to my notes:

Magic Boy was not officially released by its distributor, MGM until April 1962, although it was shown in Los Angeles in September 1961. It wasn’t reviewed in The New York Times until December 23, 1963. IMDB lists June 22, 1961 as the earliest U.S. release date.

Sasuke, the “Magic Boy” of the title, is a figure from Japanese folklore and the hero of later anime series and is seen here training in the ninja arts, cavorting with various animal friends, and battling on their behalf against an evil witch and various predatory creatures. It is, I believe, the first film with a ninja theme to be released in an English dub in the U.S., although the term “ninja” is never used on the soundtrack.

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E,” a James Bond-style secret agent series produced by MGM, was my favorite TV show back in 1964-66 and I was only ever able to watch it on a black-and-white TV set, so I was more than thrilled to see it in color when they released feature films culled from the show in theaters. Granted, the first season was, in fact, in black-and-white, but they did the pilot film in color and one other episode, which were used to create two of the U.N.C.L.E films I saw at the time, TO TRAP A SPY and THE SPY WITH MY FACE, while the third one I saw in a theater, ONE SPY TOO MANY, was made from a two-part second season episode. All were released to theaters in 1966. Several later ones made from additional two-part episodes in the 2nd and 3rd seasons would play on TV over the years. (TCM has run them all, I believe.) Here’s what I noted after a re-watch of THE SPY WITH MY FACE on TCM a few years ago: “Theatrical spin-off of “The Double Affair,” with 30 minutes of additional footage, including some very sexy shots of Sharon Farrell and an implied shower scene with Robert Vaughn and Senta Berger.”

A memorable MGM double bill I saw in 1965 boasted explosive World War II action in one film and animal antics in Africa in the other.

CROSSBOW marked the first time I’d seen the V-2 bombing of London dramatized on film. CLARENCE was soon turned into a TV series, “Daktari,” with the stars of the movie, Marshall Thompson and Cheryl Miller, repeating their roles.

POINT BLANK (1967) was an innovative crime thriller by English director John Boorman (only his second film) and shot on location in Los Angeles and on studio sets at MGM. It was based on Richard Stark’s 1962 novel, The Hunter, the first of his Parker series about a coldly professional heist man, although the character played by Lee Marvin is named Walker here and did not appear to have had a criminal background before he’s pulled into a deadly caper by an old war buddy, Mal Reese (John Vernon). With lots of flashbacks and stream-of-consciousness moments, it was quite a stylish departure for U.S. crime films and became highly influential, although it baffled studio heads at the time. Marvin’s star was on the rise, thanks to his Oscar for CAT BALLOU and his starring role in MGM’s big boxoffice hit of the year, THE DIRTY DOZEN, and he lent full support to Boorman and his unique approach, thus allowing the young newcomer to Hollywood to make the film his way.

MGM made three of its biggest hits of this period in 1967-70, all large-scale World War II action films with major stars and all among the most enjoyable moviegoing experiences I had in those years. (I’ve seen each movie many times since.) Robert Aldrich directed the first of them, 14 years after the studio produced his debut film, THE BIG LEAGUER in 1953. Brian G. Hutton directed the second and third, each of which co-stars Clint Eastwood as one of an ensemble cast. These are among the star’s best-loved films among Eastwood fans and I was stunned at how dismissive Richard Schickel was towards them in his otherwise fine 1997 biography of Eastwood.

All three movies took the WWII combat genre to new heights of absurdity, as far from the reality of war as the movies had yet gone. However, they came at a time when audiences were more receptive and even demanding of a more skeptical approach as protest movements rose up against the Vietnam War and Baby Boomer moviegoers distanced themselves from the more propaganda-themed WWII movies we’d been watching on TV since we were kids. THE DIRTY DOZEN (1967) had a pronounced anti-authoritarian streak and aroused the ire of actual World War II vets (despite the cast being largely war vets themselves) who were outraged at the tactics of “dirty war” heedlessly employed by condemned Allied military prisoners recruited for a suicide mission against a chateau filled with unsuspecting Nazi officers and their consorts.

WHERE EAGLES DARE (1969) had Richard Burton relating the most outlandish plot details (courtesy of screenwriter Alistair MacLean) with the most precise diction, making it all sound acceptable to us before he and co-star Eastwood, the only American in the cast, set out to shoot and blow up as many Nazis as possible in the movie’s last third. They’re undercover commandos infiltrating an officers’ mountain resort in the Bavarian Alps and wearing Nazi officer uniforms throughout. When they speak English among the Germans we’re to understand that they’re actually speaking German. Once you get past that, the suspension of the rest of your disbelief falls in line.

KELLY’S HEROES (1970) has outright countercultural elements sprinkled throughout, most notably Donald Sutherland’s proto-hippie tank sergeant and his slacker crew in a comic tale of a misfit reconnaissance unit who are persuaded by Private Kelly (Eastwood), who’d been demoted from Lieutenant for striking an officer, to make a foray behind enemy lines to plunder a bank containing $16 million in gold. Shot in Yugoslavia, the production used real tanks and blew up real bridges and railroad depots and reveled in some spectacular mayhem with a game all-male cast, including two members of the Dirty Dozen, Sutherland and Telly Savalas, as well as Don Rickles, Carroll O’Connor and Harry Dean Stanton.

Throughout EAGLES and KELLY, Eastwood served as the audience stand-in with his perfect glare of incredulity. Let him shoulder the burden of plausibility, we’ll just sit back and enjoy the action.

MGM continued its relationship with the Toei Studio when it co-produced a Japanese science fiction film, THE GREEN SLIME (1969), shot in Japan by a Japanese director (Kinji Fukasaku) and crew, but with an all-western cast, led by three Hollywood name actors sent over for the shoot, Robert Horton, Luciana Paluzzi, and Richard Jaeckel, supplemented by westerners who did part-time acting in Japan and others recruited from American military bases in the region and a contingent of Israeli medical students to fill out the cast. (Horton had acted for MGM before and Jaeckel had co-starred in THE DIRTY DOZEN.) I love the film and have written about it here.

MGM produced MARLOWE (1969) with James Garner as private eye Philip Marlowe, based on Raymond Chandler’s 1949 book, The Little Sister. This was the first big-screen Marlowe adaptation Hollywood had attempted since THE BRASHER DOUBLOON (1947). Of note is the appearance of post-Green Hornet Bruce Lee as Winslow Wong, a henchman who threatens Marlowe, tries to bribe him and winds up trashing his office in L.A.’s Bradbury Building in one memorable scene. (Lee has one later scene as well.)

THE 5-MAN ARMY (1969) is a hybrid American-Italian western co-directed by former MGM contract actor Don Taylor and starring an interesting hybrid cast of Peter Graves, James Daly, Italian western star Bud Spencer (aka Carlo Pedersoli), Italian actor Nino Castelnuovo and Japanese star Tetsuro Tanba (Tiger Tanaka in the James Bond film, YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE). With music by Ennio Morricone.

NO BLADE OF GRASS (1970), directed in England by Hollywood star Cornel Wilde (the only film he directed that he doesn’t appear in), is a dystopian ecological drama showing people in England fighting over land, food and water at a time when society breaks down and citizens have to take up weapons to protect what they have or pillage what they don’t have from others. I remember it being quite bleak and I’d love to see it again. The lack of any Hollywood names gives it a ringing authenticity that other post-apocalyptic films can only attempt. Sadly, it did not get a wide release and I had to wait till the Museum of Modern Art showed it a few years later.

GET CARTER (1971), a working-class English crime thriller directed by Michael Hodges and starring Michael Caine, is a film I’d only seen once in an edited-for-television broadcast version years ago until I re-watched it recently on TCM, which ran the uncut, R-rated version. It’s a tale of a London mobster who travels to his hometown to investigate his brother’s “accidental” death and finds himself caught up in a gang war involving a local porno ring. Here’s some of what I noted: “Gritty, grim, brutal, relentless, violent, sexy, rough. Carter is vicious….Very nicely staged and shot amidst grimy locations in Newcastle.”

MGM helped to get Blaxploitation off the ground with SHAFT (1971), starring Richard Roundtree (in his film debut!), filmed in New York by renowned black photographer Gordon Parks, only his second feature, and the first film to feature a black private eye. I wrote about it here.

Its success insured a steady stream of black crime thrillers from MGM, including COOL BREEZE (1972), a black-cast remake of MGM’s earlier classic caper movie, THE ASPHALT JUNGLE; HIT MAN (1972), a rather quick remake of the previous year’s GET CARTER, transplanted to L.A. and starring Bernie Casey and Pam Grier; MELINDA (1972), a sexy thriller about a popular black DJ (Calvin Lockhart) who studies martial arts under Jim Kelly (a year before ENTER THE DRAGON); and two SHAFT sequels, SHAFT’S BIG SCORE (1972) and SHAFT IN AFRICA (1973).

This latter film is quite the reversal of an MGM hit from 30 years earlier:

During this period, I also saw some MGM classics as Saturday children’s matinees.

Like THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939), THE SECRET GARDEN (1949) begins in black-and-white and turns into Technicolor. It happens in GARDEN at the point, about half-way through the film, where the garden tended back to life by the children finally flourishes and I remember the audience, not used to seeing black-and-white films in theaters by this point in 1972, gasping in awe at the transition to beautiful color.

Believe it or not, but THE SECRET GARDEN (1949) matinee showing was immediately followed by a double bill of thrillers from American International Pictures, THE THING WITH TWO HEADS and BARON BLOOD. As I recall, the entire audience stayed for it and I can assure you that a good time was had by all.

What may be my favorite MGM crime film from the 1970s is, like POINT BLANK, based on a Parker novel by Richard Stark. THE OUTFIT (from the 1963 novel of the same title) was directed by John Flynn and stars Robert Duvall (as the Parker stand-in, Earl Macklin) and Joe Don Baker as a robbery team who marshal their resources to go after mob-controlled businesses with lots of ready cash for the taking. It has a once-in-a-lifetime cast of veteran movie tough guys headed by Robert Ryan as the mob boss whose operations are targeted by the two protagonists and including a multitude of other familiar faces popping up as either friends or foes along the way (Richard Jaeckel, Jane Greer, Timothy Carey, Elisha Cook, Marie Windsor, Archie Moore, Tom Reese, Emile Meyer, etc.). It was produced by MGM, but distributed by United Artists and didn’t get the wide release it deserved. I had to wait till it came on broadcast TV to finally see it.

MGM’s earlier forays into science fiction yielded three of the genre’s all-time classics, FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956), THE TIME MACHINE (1960) and 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968). Two 1973 entries may not be in quite the same league, but they both turned out to be highly influential.

WESTWORLD resulted in a sequel from another company, FUTUREWORLD (1976, American International Pictures), that I remember liking even better, and was recently remade as a much-talked-about TV series in 2016 for HBO Max. SOYLENT GREEN’s closing line continues to resonate in our culture. Both WESTWORLD and SOYLENT GREEN were among the last features made on MGM’s massive backlot, which was soon demolished by the studio for sale to land developers. In his audio commentary on the DVD for SOYLENT GREEN, director Richard Fleischer claims it was the last film shot on the backlot. He used the New York street set for much of the action and since it was already somewhat in disrepair, it fit in perfectly with the dystopian landscape he was trying to craft for the film, set in 2022 in an overpopulated New York City with 40 million people!

Judging from the extras recruited from Central Casting for SOYLENT GREEN, everyone seems remarkably fit, young, well-fed and groomed despite being poor, hungry masses!

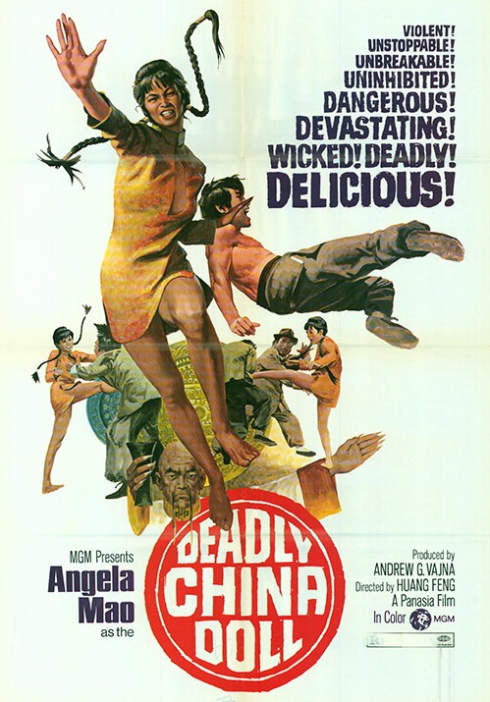

When I saw WESTWORLD, it was on a double bill with DEADLY CHINA DOLL, the only Hong Kong kung fu film released by MGM during this period. It starred Angela Mao.

I’ll close with PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID (1973), which I last wrote about here. Sam Peckinpah’s tragic tale of the final days in the relationship between lawman Pat Garrett (James Coburn) and wanted outlaw William Bonney, aka Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson) represents the most egregious example of production head James Aubrey’s interference with filmmakers. The version I saw in a theater back then was Aubrey’s 106-minute cut. In contrast, the restored director’s cut released in 1988, four years after Peckinpah’s death, was 122 min. and the so-called “TCM cut” from 2005 is 115 min., both of which are on DVD. (I have the theatrical cut but only on VHS.) Peckinpah was interviewed a year after Aubrey’s unceremonial departure from MGM, and he was quoted as saying, “I trust he’s a bellhop at the MGM Grand now.”

The longer versions include a prologue which takes place over 20 years later and scenes involving various additional characters, including Garrett’s Mexican wife Ida (Aurora Clavell) and powerful rancher John Chisum (Barry Sullivan) that provide much-needed context for the action.

I recently re-watched the TCM cut of PAT GARRETT and the original theatrical cut and here was my reaction to the shorter version:

It’s like a minimalist version of Peckinpah’s film, stripping everything down to the alternating journeys of Pat (James Coburn) and Billy (Kris Kristofferson) as they leave each other after their last friendly drink together in the opening sequence and begin the slow circling around, before their final fateful meet-up in Fort Sumner. The only music consists of musical cues and songs provided by co-star Bob Dylan. Regardless of this version’s critical reputation, I recall how rapt the Saturday afternoon audience was at the Bronx theater where I saw it 50 years ago (on a double bill with the Blaxploitation hit MELINDA). This was a largely male adult audience, mostly black and Latino, and solid western fans. They liked it.

All this happened before the studio celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1974. One of the events was a months-long retrospective of MGM films that spring at the Museum of Modern Art. I attended many of the screenings, including a showing of the brand-new compilation film, THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT!, in which many of MGM’s biggest stars, led by Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra, Debbie Reynolds, Bing Crosby and Mickey Rooney, introduced clips from the studio’s many musicals. One poignant host sequence featured Astaire walking among the ruins of the train station set where he’d sung “By Myself” in THE BAND WAGON 20 years earlier.

In any event, MGM continued to put out occasional productions that attracted my patronage over the next decade, and I saw at least 36 MGM releases in theaters throughout the 1970s, including such later releases as THE SUPER COPS (1974), LOGAN’S RUN (1976), TELEFON (1977), and COMA (1978).

MGM acquired United Artists in 1981 and it continues to exist as a corporate entity in some form or other. I’m currently reading Fade Out: The Calamitous Final Days of MGM, by Peter Bart, who served as an executive with the studio in the 1980s and watched its decline up close. It’s pretty astounding how few of the films made under the later regimes I bothered to see, essentially just two in theaters, FAME (1980), about my old high school, and CLASH OF THE TITANS (1981), Ray Harryhausen’s final mythological special effects extravaganza, and a couple more on VHS rentals, RED DAWN (1984) and YEAR OF THE DRAGON (1985).

Bart mentions CLASH OF THE TITANS only once in passing and dismisses it as “schlocky.” What would Zeus say to that?

The MGM physical studio–what’s left of it–was eventually taken over by Sony Pictures, which is situated there today and which I visited in 2009.

Turner Classic Movies now controls the classic MGM library (along with those of United Artists and pre-1948 Warner Bros.) and I’m extremely grateful for the TCM cable channel and its DVD releases of MGM classics like these (under the Warner Home Video label):

I was originally planning to do this post as a tribute to my 50 favorite MGM films of all time. Ten of the twelve depicted on these DVD covers are on my list. Eleven others on my list are cited earlier in the post.

Leave a comment