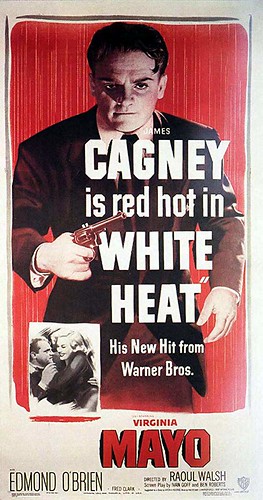

On September 3, 1949, 70 years ago today, Raoul Walsh’s crime thriller, WHITE HEAT, opened in the U.S. Its star, James Cagney, was renowned in the 1930s for his gangster portrayals in such films as PUBLIC ENEMY, G-MEN, and EACH DAWN I DIE, but he hadn’t made a crime film at all in the ten years since the prohibition saga, THE ROARING TWENTIES (1939), also directed by Walsh. During that time, Cagney made war films, comedies, melodramas and the flag-waving musical, YANKEE DOODLE DANDY. By 1949, gangster fans were itching for the old Cagney, while younger filmgoers needed to be reminded what he was most famous for. The original trailer for WHITE HEAT is chock full of violent, graphic action, with Cagney a relentless, murderous force, snarling, punching and shooting his way through a quick, brutal rehash of the film’s plot in three minutes: train robbery, prison, daring escape, pursuit by the Feds, and an explosive climax at a chemical plant in Southern California. Older fans were beside themselves with gleeful anticipation, while the younger ones’ jaws dropped. As the trailer put it, “It’s your kind of Cagney / In his kind of story / Blazing his way to the top of the world!”

I saw this trailer at a repertory theater in 1979 (the Thalia in Manhattan), 30 years after the film’s release, and I can assure you that the audience buzz it generated had to have been equal to that in 1949. When the film played the following week, the place was packed.

WARNING: this must-see trailer is filled with spoilers and features several of the film’s most memorable lines:

Of course, spoilers and all, it will still make you want to see the film.

Cagney plays Cody Jarrett, a bandit leader accompanied by his devoted mother and a demanding, money-hungry wife, as well as a crew of seasoned, ruthless heist men. Jarrett runs his gang with an iron hand.

At one point early on, he eyes his confederate, Big Ed (Steve Cochran), and the easy rapport he has with Jarrett’s wife, Verna (Virginia Mayo), and declares, “If I turn my back long enough for Big Ed to put a hole in it…there’d be a hole in it.”

Jarrett’s weakness is his tendency towards migraine headaches, which render him helpless until his mother, Ma Jarrett (Margaret Wycherly), can soothe him and ease the pain. When Jarrett goes to prison, admitting to a job he didn’t pull which gives him an alibi for one he did pull which left three railroad employees dead, the Treasury Department allows the deceit to stand so they can put an undercover agent, Hank Fallon, aka Vic Pardo (Edmond O’Brien), in Jarrett’s cell to try and gain his confidence to find out where Jarrett unloads the currency, bonds and securities he steals. Jarrett later pulls off an elaborate escape, after which he reunites with his gang and plans a military-style payroll robbery. A lot more happens in between all of this, but I’m avoiding spoilers so as to encourage those of you who haven’t seen it to see it for yourselves.

The film is full of incident, much of it shot on location, with action scenes that are as exciting as any I’ve seen in a Hollywood film in the years prior to Sam Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH (1969), starting with the train robbery, continuing with a car chase through Los Angeles, Jarrett’s first confrontation with a Federal officer, a fight scene in prison, Jarrett going berserk in the prison mess hall, a bold escape, the chemical plant robbery and the furious gun battle between cops and criminals, culminating in the famous line, “Made it, Ma, top of the world!” and its deadly aftermath. There was really nothing quite like it up to that time, with the exceptions of specific action scenes in three gangster films of the 1930s: Howard Hawks’ SCARFACE (1932), William Keighley’s G-MEN (1935), and Walsh’s THE ROARING TWENTIES, the latter two also starring Cagney. But none of them offers a tone anywhere close to the hard-bitten, unsentimental ferocity of WHITE HEAT.

I would argue that WHITE HEAT was THE WILD BUNCH of its time, both of them escalating the level of violence onscreen, stripped of romance and depicting hardened killers and gun-toting outlaws facing the end of their era. In WHITE HEAT, it’s advances in technology that aid the Feds in bringing down the gang, while in THE WILD BUNCH, it’s the encroaching power of corporations, as embodied by the railroad and its ability to devote significant resources to the pursuit and destruction of the Bunch, as well as the outlaws’ ill-fated collision with political conflicts, military rule and revolutionary movements in a neighboring country.

The two movies share a cast member in common, Edmond O’Brien, who plays Old Man Sykes, a veteran member of the Bunch in the later film.

The men in WHITE HEAT don’t look like standard movie gangsters, but like real-life working-class men of the postwar era. When I first saw this film as a child, I was struck by how much the men in it resembled the Irish blue collar fathers who frequented the bars in my neighborhood that my father, a white collar worker, also patronized.

I actually first watched this film with my father when I was a child and a Mets baseball game had been rained out. Since the movie played in the baseball time slot, it was never identified by the station broadcasting it and my father didn’t recognize it at all. He did, however, note the resemblance of Ma Jarrett to 1930s crime figure Ma Barker. I knew who James Cagney was (from YANKEE DOODLE DANDY) and remembered his character name, Cody Jarrett, but I didn’t recognize the other lead actor at the time (O’Brien) and for years afterwards, in remembering the movie and trying to identify it, I assumed he was Humphrey Bogart. One time I even watched PUBLIC ENEMY (1931), Cagney’s breakthrough film, on TV hoping that was it. Nope. It wasn’t until high school when I went into a public library reference section in Manhattan for the first time and went through several film reference books that I was finally able to identify the film by name and learn that it was Edmond O’Brien and not Bogart in the second leading role. I didn’t see the film a second time till a late-night TV showing when I was in college. I would soon see it several times on the big screen at revival theaters and many times since. It’s now one of my favorite films.

I once researched critical reaction to White Heat and while it was generally upbeat, some commentators were outraged by the film’s amoral elements. Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review is worth quoting for the way it hedges its otherwise favorable comments with a concern for “moral values” and its colorful detailing of the enthusiastic response of a youthful audience member at the Broadway movie palace at which the film premiered. In a Sunday arts piece dated September 11, 1949 and printed a week after Crowther’s daily review of the film, thus putting it firmly under the heading of “second thoughts,” Crowther closes by lamenting the fact that “Mr. Cagney has to come back to this sort of thing”:

“For the innocent thrills and amusement—yes, amusement–which a well-designed ‘White Heat’ can give to large segments of the public are balanced, we feel sure, by the unhealthy stimulation which such a film affords the weak and young. And the notions it spreads of moral values are dangerously volatile.

“For inevitably Mr. Cagney, the bold and indomitable, appears a remarkable hero in this modern-jungle film. He loves his mother, he is scrupulously loyal to the best interest of his gang, he is brave, he detests a two-timer and he won’t compromise with the law. The irony of his brief existence, as it seems at the last to be revealed, is not that he took to killing because of a misguided youth but that, in his grief and desolation, he was outsmarted by a clever cop. We heard a kid in the audience at the Strand the other day greet one of his vicious capers with a rhapsodic ‘Bee-you-tee-ful!’ The echo rang grim and horrendous in that youngster-packed theatre.”

I’m curious to know which “vicious caper” elicited such an excited reaction. My guess has always been the bit at the motor lodge where Jarrett is surprised in the act of fleeing by zealous Treasury agent Evans (John Archer). Jarrett has just slipped behind the wheel of his car when Evans gets the drop on him. Jarrett puts his hands up, as ordered, retrieves a pistol from its perch in the sun visor and immediately spins and shoots Evans, wounding him, before driving off with Ma and Verna. In a word, ‘Bee-you-tee-ful!’

Years after the film’s release, attesting to its continued popularity in the grindhouse theaters of New York’s 42nd Street, William S. Pechter, in a 1967 piece celebrating the film (reprinted in Twenty-four Times a Second, Harper, 1971), declared, “I don’t know where on earth one can get to see White Heat now off of Forty-second Street; probably, its violence would proscribe it even from television, where most of what was great in the American film now writhes under the cutter’s knife.”

Photographic proof that WHITE HEAT was indeed playing 42nd Street as late as 1957, when this was taken:

I previously wrote about WHITE HEAT in my centennial pieces on Edmond O’Brien and Steve Cochran. Those write-ups, however, are filled with spoilers, so see the movie first!

Leave a comment