I was meaning to do a piece on the 25th anniversary of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, but I got sidetracked around the time of the anniversary (last August) and then worried how I could tackle such a broad subject in a single entry. I’m glad I waited because I recently came across a long-buried file containing press coverage of the Power Rangers from 1993-95, when the franchise got its heaviest media exposure. I’ve scanned some of these articles (from TV Guide and other sources) and pasted them below. Also, I got to see the very last episode of the current and 25th season, “Power Rangers Super Ninja Steel,” which aired on the Nickelodeon cable channel on December 1, 2018.

As someone who’s watched every season since its premiere, I was amused to look back and re-read the critical comments about the show during its first season, but also somewhat frustrated. The fact remains that the franchise has introduced new seasons every year since 1993 for a total of 875 episodes so far and its later seasons, including some of the franchise’s best, got very little press coverage. To the best of my knowledge, no professional critics have been following the show at all in the last two decades. While the early seasons were flawed in many ways, with sloppy scripting and awkward integration of Japanese action and effects footage with American-shot scenes, the franchise did get better over the years with a solid behind-the-scenes team of writers, directors and producers insuring quality control and pushing for better scripts and, eventually, seamless integration of high-def Japanese and American footage. Also, beginning with “Power Rangers Lightspeed Rescue” (2000), the franchise began adapting the original Japanese seasons more closely, with each episode making better use of the original storylines. (This was done occasionally in earlier seasons as well, but not consistently.) I’ve made a point of following the original Japanese Super Sentai seasons as well.

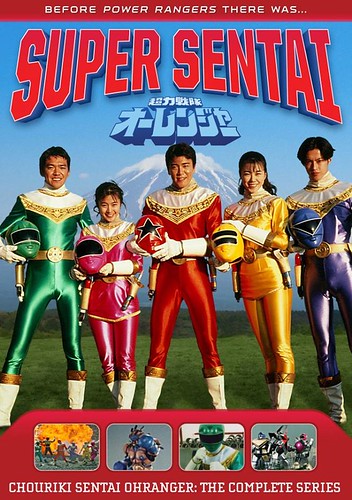

It’s been a big help that the Power Rangers seasons have been coming out in box sets from Shout Factory and to make matters even better, the same company has been releasing the original Super Sentai seasons with eleven of them, covering the years 1991-2001, already available in box sets in Japanese with English subtitles. They began in 2015 with “Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger,” the 1992 season that provided the basis for the first couple of seasons of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, and have most recently released the 2001 season, “Hyakujuu Sentai Gaoranger,” the basis for 2002’s “Power Rangers Wild Force.” During this time they also released “Chojin Sentai Jetman” (1991), which was never adapted into a Power Rangers season and remains one of the very best sentai seasons I’ve ever seen. (I’m planning a full review in a future blog entry.)

And the big news is that the new season of Power Rangers, set to premiere on Nickelodeon on March 2, 2019, will be called “Power Rangers Beast Morphers” and is based on the 2012 sentai season, “Tokumei Sentai Go-Busters,” marking the first time the franchise has gone back and adapted a season it originally skipped over. I’m a big fan of “Go-Busters,” not least because it was the first sentai season to adopt the original Mighty Morphin catch phrase, “It’s morphin’ time.” When I watched episodes of “Go-Busters,” it struck me as a mix of two American franchises, “Transformers,” thanks to its transforming vehicles, and “Mission: Impossible,” with its high-tech spy team taking the job of “Go-Busters.”

Here are some of the articles I found in my file.

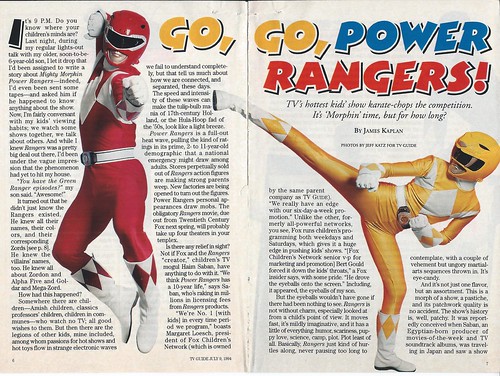

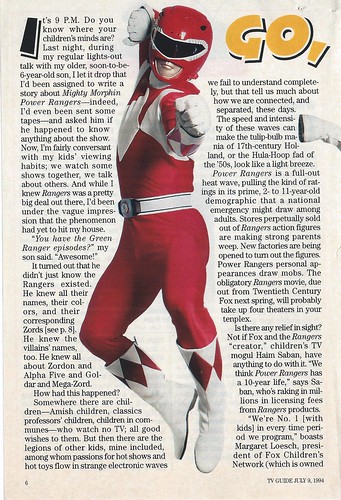

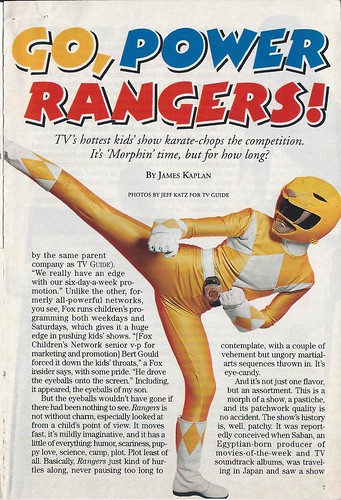

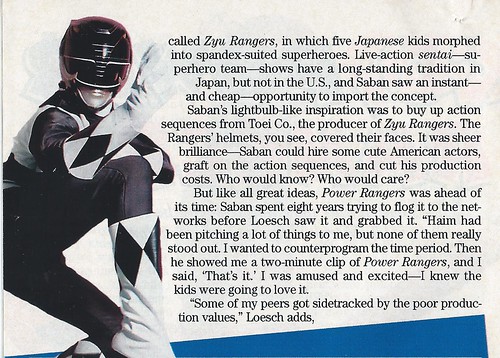

In this TV Guide article, “Go, Go, Power Rangers” (July 9, 1994), by James Kaplan, we read a quote from executive producer Haim Saban, the one who came up with the idea for turning Super Sentai into an American franchise and shepherded it through production and syndication.

Saban: “We think Power Rangers has a 10-year life.”

Little did he know.

Kaplan adds, towards the end of the piece: “Can the live action endure, like the Ninja Turtles—on the air for four years now—or will it go the way of the Cabbage Patch Kids and Teddy Ruxpin? Saturation is the downfall of crazes and the Rangers have reached a lot of markets. And live-action sentai gets old fast.”

Not to me it doesn’t. And the sentai franchise has been on the air in Japan since 1975.

Here is Kaplan’s initial take on the series: “Rangers is not without charm, especially if looked at from a child’s point of view. It moves fast, it’s mildly imaginative, and it has a little of everything: humor, scariness, puppy love, science, camp, plot. Plot least of all. Basically, Rangers just kind of hurtles along, never pausing too long to contemplate, with a couple of vehement but ungory martial-arts sequences thrown in. It’s eye candy.”

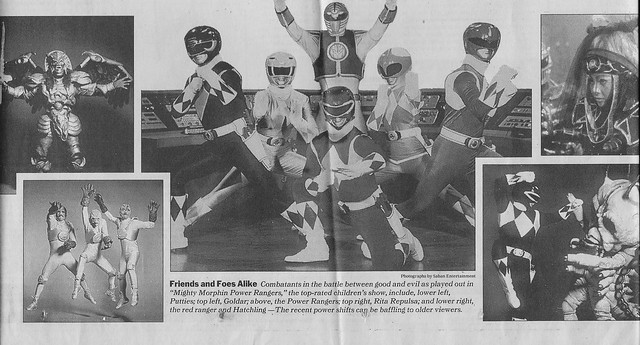

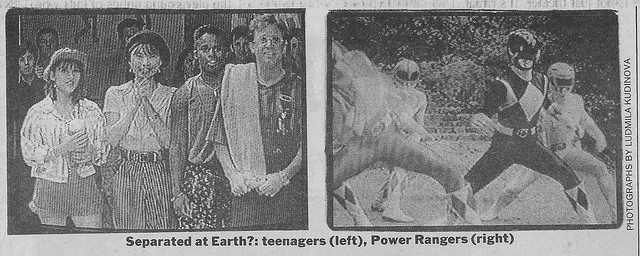

Various sidebars looked at different aspects of the Power Rangers phenomenon:

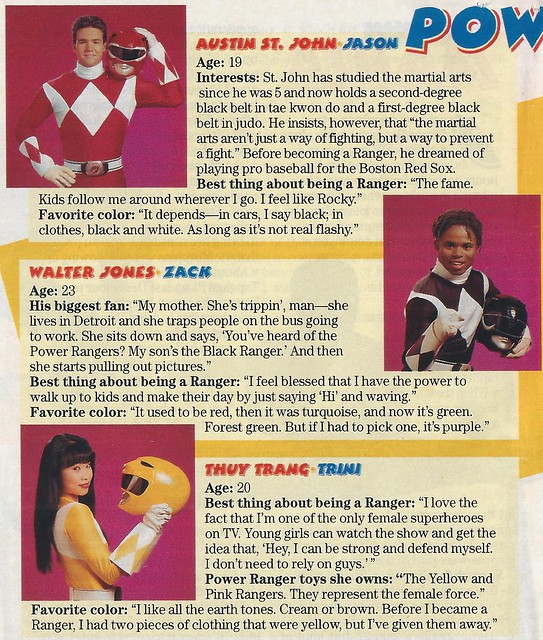

There was also a look at each of the six actors making up the Power Rangers:

That issue even gave us a gallery of MMPR monsters:

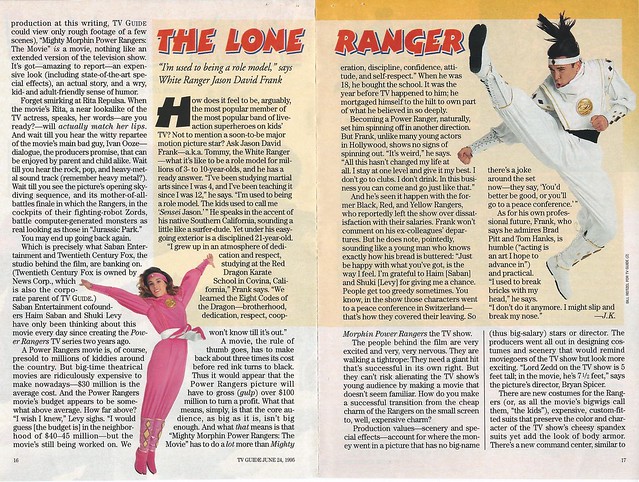

Also from TV Guide: “It’s Morphin Time!” (June 24, 1995), also by James Kaplan.

This one hypes the then-new feature film based on the series and is upbeat about it because it’s all new and doesn’t use any Japanese or made-for-TV footage.

Kaplan: “From early indications (because the film was in post-production at this writing, TV Guide could view only rough footage of a few scenes), “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie” is a movie, nothing like an extended version of the television show. It’s got—amazing to report—an expensive look (including state-of-the-art special effects), an actual story, and a wry kid- and adult-friendly sense of humor.

“Forget smirking Rita Repulsa. When the movie’s Rita, a near lookalike of the TV actress, speaks, her words—are you ready?—will actually match her lips.”

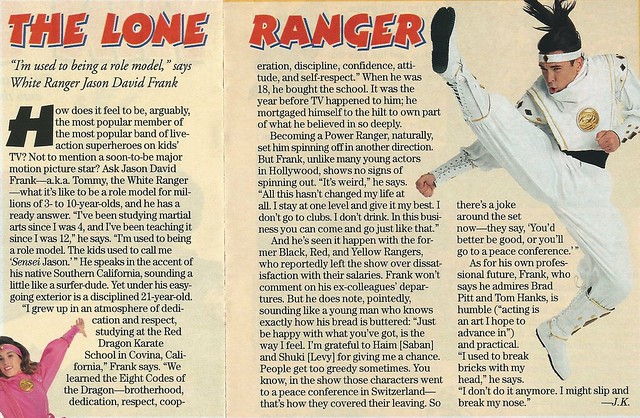

A sidebar profiles Jason David Frank, who played Tommy, who was, at different points in the first four seasons, the Green Ranger, the White Ranger and the Red Ranger:

Much of the press at the time was about the mania for Power Rangers toys, merchandise and public appearances. This Newsweek article, subtitled “These TV heroes are now exceeding their marketers’ wildest dreams,” focuses more on the business than the aesthetics, although the author manages to dub the show both “cheesy” and “clumsy.”

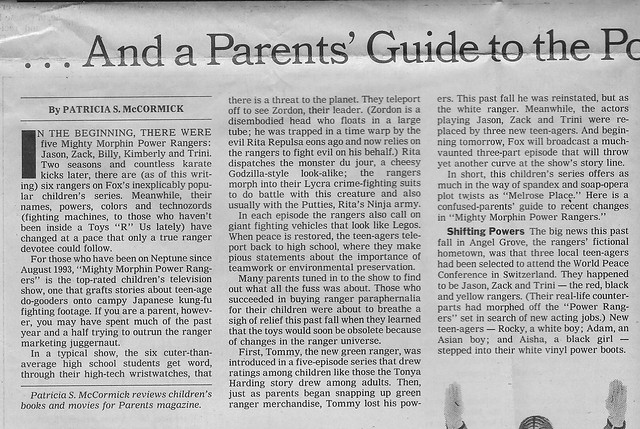

17 months after MMPR’s premiere, The New York Times offered “A Parents’ Guide to the Politics of Angel Grove,” by Patricia S. McCormick, who revealed her bias in the first paragraph when she referred to the series as “Fox’s inexplicably popular children’s series.” Inexplicable? Hello?! At least Mr. Kaplan in TV Guide made an effort to make it explicable. McCormick goes on to describe a series of new plot developments and then adds, “In short, this children’s series offers as much in the way of spandex and soap-opera plot twists as ‘Melrose Place.’ Here is a confused-parents’ guide to recent changes in “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.”

Only in the Village Voice, an alternative weekly in New York City, did I find an assessment by someone who’d actually watched a lot of episodes and was keenly aware of its Japanese origins.

In “Half Japanese: Power Rangers Corrupt? Absolutely” (June 21, 1994), despite the use of “corrupt” in the header, critic Erik Davis writes appreciatively of the notion of a Japanese-American hybrid and predicts (accurately) the show’s function as an entry point for future fans of Japanese pop culture:

But when they morph, the American team doesn’t just don costumes, they mutate their core identities. The rough transition and lack of continuity between the Japanese and American footage is a sign not only of Saban’s bargain-basement editing but of the dreamlike and monstrous scrambling of cultural codes. Our Wonder Bread heroes are not just turning Japanese, they’re becoming altered beings in a parallel aesthetic realm, with its own internal logic, myths, and ethics. And maybe their audience is somehow transforming too.

Of course, American kids have long enjoyed dollops of Japanese culture: Astro Boy, Speed Racer, Ultraman, Transformers, and the granddaddy of them all, Godzilla. But the Power Rangers craze dwarfs these fandoms. The tykes currently addicted to the show may end up becoming a mass market for more mature and vital Japanese popular arts now shrouded in hipster subculture–e.g. anime (Japanese animation) and manga (Japanese comic books).

Davis adds:

Initially, even hardcore camp aesthetes may find Mighty Morphin Power Rangers’ particular flavor of cheese difficult to get down. But after watching the show as it was designed to be watched—day after day after day—what I previously saw as tacky fodder grew into a rich aesthetic vision. The discontinuous and repetitive Japanese fight scenes are so hyperstylized they play like postmodern acrobatics, while the shots of samurai robots smashing up toy cities are so low-budget they give off a dreamy, childhood glow. Even the hack frisson of the American-Japanese cultural splice makes the series crackle with a frazzled, unintentionally avant-garde buzz.

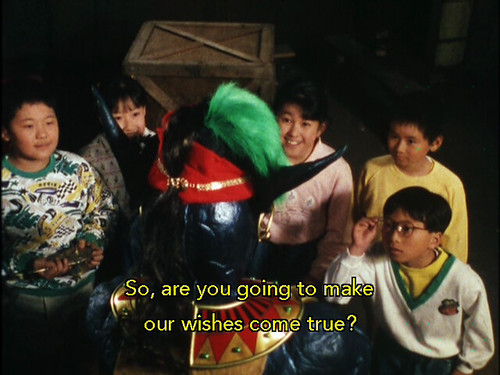

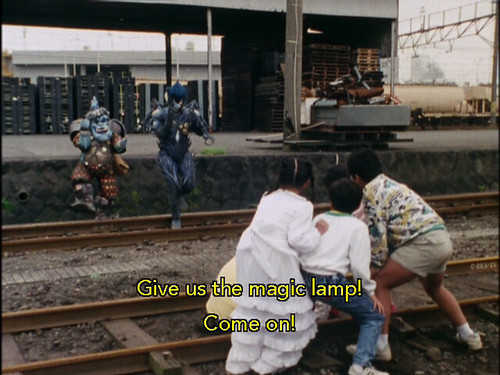

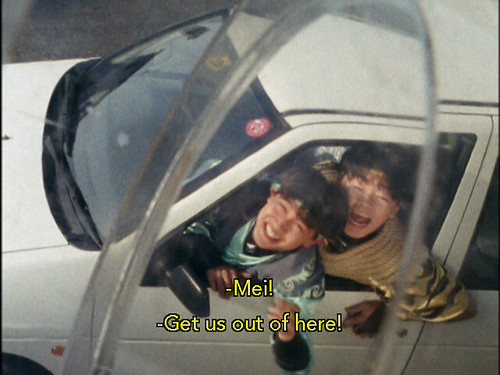

In preparing this piece, I also watched a number of episodes from the first season of MMPR, as well as the corresponding episodes from the Japanese original, “Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger,” which ran on Japanese television in 1992. I tend to find the scripts more cohesive in the Japanese series with more imaginative ideas employed in the plotting and interesting and eccentric supporting characters added to the mix. For instance, in one charming episode of Zyuranger, #11: My Master!, an old lamp containing a genie changes hands several times in the course of the show. When a group of six children—three girls and three boys—gain control of it, they ask the genie to supply them with snacks, manga, a sports car, a new dress and, for one girl who wants to fly, a magic carpet. We get a delightful sequence where the kids are clearly enjoying their bounty. When the villains get hold of the lamp, however, they turn the genie into a giant to rampage through Tokyo until the Zyurangers transform and enter their zords and combat it, finally getting hold of the lamp themselves and restoring the genie to it without harm.

When this episode was adapted for MMPR, they grafted a completely different plot onto it, about Kimberly (Pink Ranger) and Billy (Blue Ranger) switching bodies, and use the genie footage only in the zord battle as a generic monster. It struck me as a wasted opportunity.

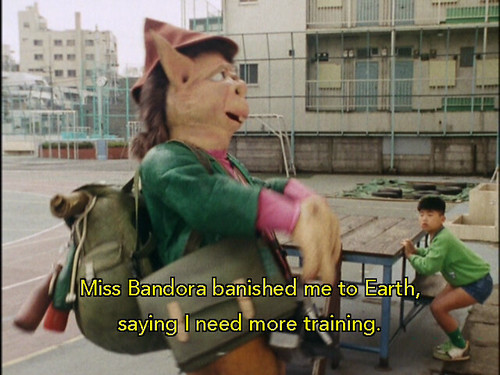

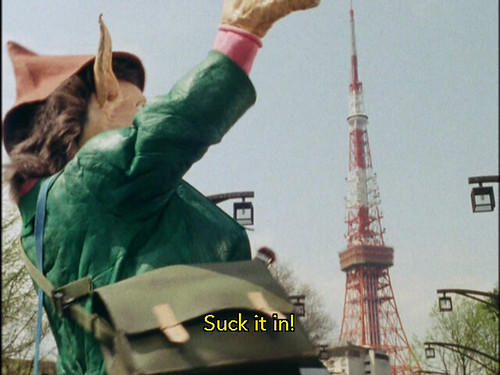

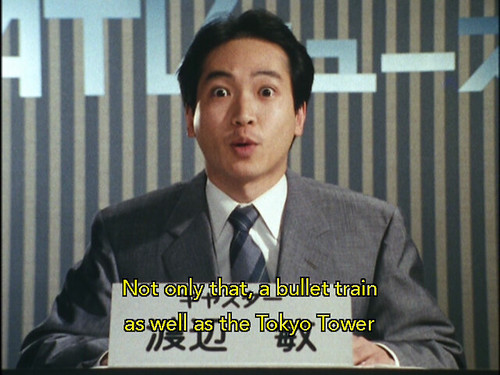

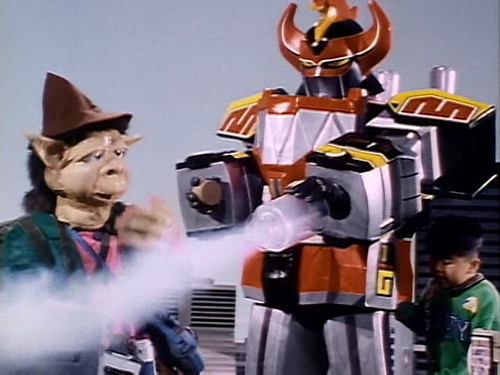

However, another Zyuranger episode, #14: Become Small!, was adapted for MMPR quite closely with much of the footage from the Japanese show used to great effect. In the original, a dwarf from the “Secret Woods,” labeled Fairy Dondon, is rejected by the villain, Witch Bandora, when his “monster” creations are too benign and too “festive.” Meanwhile, a schoolboy named Toshio, yelled at by his mother and berated by his teacher, runs away from school and winds up tagging along with the equally outcast Fairy Dondon, who has a series of magic bottles that he uses to capture and shrink things—a passenger plane in flight, a commuter train in motion, an entire office building, and, finally, Tokyo Tower itself! When two of the Zyurangers, Dan (Blue) and Boi (Yellow), follow them in a car to try to get them to stop, they’re sucked into a bottle, car and all, as well. Bandora turns both Dondon and the boy into giants to rampage through Tokyo until the Zyurangers, with help from the boy’s mother, shame them into returning everything they captured and restore them to normal size. It’s an extremely clever and funny episode.

In the MMPR adaptation of this episode, #9: For Whom the Bell Trolls, Fairy Dondon becomes a doll named “Tickle Sneezer” owned by Trini (Yellow Ranger) that is then brought to life by Rita Repulsa (the renamed Witch Bandora). The footage of Dondon shrinking things is included, including Tokyo Tower which has been magically transplanted to the Rangers’ hometown of Angel Grove, California! Trini and Billy even drive the same make of car that the two Zyurangers did and get sucked into the bottle, with shots of them expertly intercut with the Japanese footage, although there is also new footage of Dondon/Tickle Sneezer shot by the U.S. crew for the sequence.

However, they had to cut out all the footage of poor Toshio, although he remains visible in one shot during the climactic zord battle as he cowers behind the Power Rangers’ megazord in the lower right hand corner of the frame, as seen here:

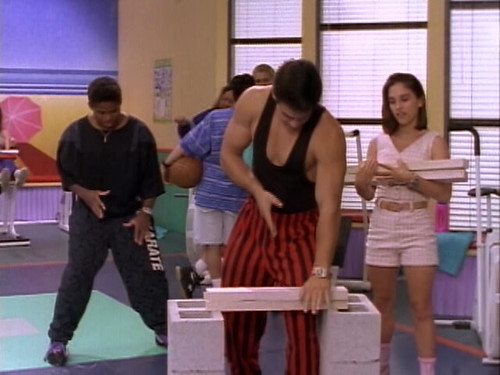

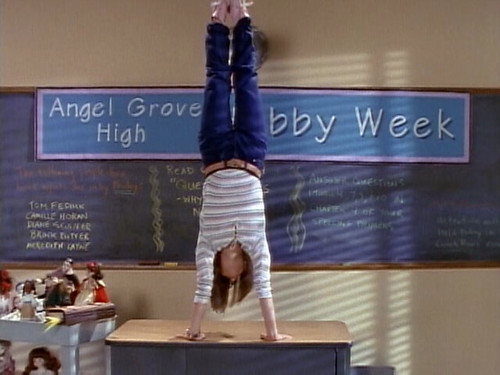

Where MMPR truly improved on Zyuranger is in the development of its characters. The Power Rangers are all distinct from each other and have lives and interests of their own. The camaraderie they develop in the course of their adventures is quite convincing and we soon see how much they care for each other and support each other’s individual pursuits. At the same time, constant training is prioritized and we see lots of scenes of the Rangers doing physical training and sparring in martial arts on their own, as well as other forms of practice, such as Kimberly with her gymnastics and Zack with his dancing.

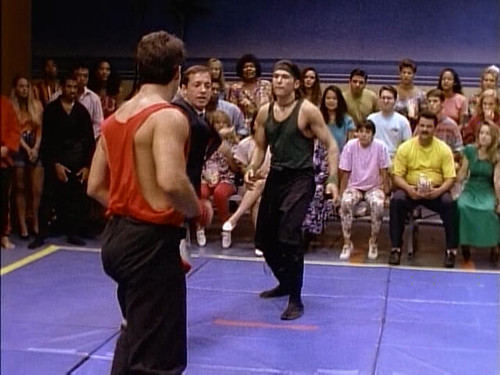

In MMPR #26: “Gung Ho!,” Jason (Red Ranger) and Tommy (Green Ranger) spend time training for an upcoming tournament and learn to work together more closely, enabling them to beat their opponents in an exciting match seen in its entirety at the end of the episode.

It was episodes like this that made me wonder why we couldn’t have had a whole subgenre of martial arts films in the ’90s starring cast members who’d graduated from the Power Rangers, e.g. Austin St. John and Jason David Frank. It was, after all, an era in which martial arts stars like Chuck Norris, Steven Seagal and Jean-Claude Van Damme were still popular at the multiplexes and Cynthia Rothrock was a mainstay of direct-to-video martial arts films.

The Power Rangers also spend a lot of time teaching and interacting with students, usually children. Jason and Tommy are both seen teaching martial arts to a succession of young students. Zack teaches a combo of martial arts and dance moves, dubbed “Hiphopkido,” to kids and Billy mentors young inventors for their science projects.

This is in contrast to the five young members of Zyuranger, who are revived ancient warriors bound by their shared past (170 million years ago!), but don’t seem to have much in the way of character and little motivation beyond their destined mission to recapture Witch Bandora, at least as far as I can tell from the first 20 episodes. Neither Geki (Red) nor Goushi (Black) have much in the way of personality, while Mei (Pink) is much more self-effacing and less assertive than her counterpart, Kimberly, in MMPR, although that changes in the later episodes. Only Dan and Boi (Blue and Yellow), the two youngest, boast the kind of youthful energy we see in MMPR and actually get into arguments with people and each other. We also see them (and Mei) interacting with children a lot, just like the Power Rangers. The villains in Zyuranger, led by Witch Bandora and her protégé Lamy (Scorpina in MMPR), had the more interesting and complicated relationships.

Most sentai series, however, placed an acute dramatic emphasis on the relationships, both good and bad, that the team members form. “Chojin Sentai Jetman,” for instance, the season that preceded “Zyuranger,” boasted five of the most richly detailed characterizations I’ve ever seen in one of these seasons, not to mention strong characters among the villains as well. There’s a love triangle among the five members of Jetman that I will devote attention to in a future entry.

December 1, 2018 marked the end of the 25th season of “Power Rangers Super Ninja Steel” (the follow-up to 2017’s “Power Rangers Ninja Steel”). Both “Ninja Steel” seasons were based on the 2015 sentai season, “Shuriken Sentai Ninninger,” one of several sentai seasons which offered a ninja theme and which I saw in its 47-episode entirety last year. (The two seasons of Ninja Steel added up to 44 episodes total.) The teens in Ninninger were descendants of an ancient ninja clan, a status shared with two of the teens in “Ninja Steel” who are described as sons of “Earth’s greatest ninja.” The other Power Rangers in “Ninja Steel” are ordinary high school students.

I enjoyed “Ninja Steel,” even though I don’t consider it among the best of recent PR seasons. (See Power Rangers: 24 Seasons and Counting.) The storylines tended to be on the preachy side (don’t cheat, don’t break the rules, don’t get overconfident, etc.) and there was too much comic relief from Victor Vincent, a conceited over-achiever in the school and his obsequious sidekick Monty, who are always trying to get the edge over everyone else and steal the Power Rangers’ thunder. They even ally with the bad guys when it’s expedient for them. Granted, it’s aimed at children, who could certainly use such lessons, and I know my eight-year-old self would have been delighted to have this series. Besides, I really enjoyed the scenes of the six team members conducting their normal everyday lives and interacting with others at school, including the principal, faculty and other students, and with people in the community. Each of them has a life beyond the Power Rangers and specialties of their own. We even meet several parents of the team members, something not often seen in Power Rangers. And the Rangers’ camaraderie seemed genuine. Also, two of the Ninja Steel teammates, Hayley (Zoe Robins) and Calvin (Nico Greetham), are already in a romantic relationship at the time they become Power Rangers. They’re casually affectionate with each other quite often and over the course of two years, their relationship withstands various squabbles and disappointments—just like a real couple. There’s an emotional honesty about their relationship and the two actors behaved like real people. I was very moved.

If I just count the Shout Factory releases, I now have over a thousand Super Sentai and Power Rangers episodes on disc, with more to come, dating from 1991 to the present. (And hundreds more on VHS tape.) Plus I have access to most of the 21st century Super Sentai series, but in Japanese without subtitles. I’m not sure I’ve seen even half of these episodes. I believe I’ve seen only about nine seasons total in their entirety, six from the U.S. and three from Japan. I’ve got my work cut out for me.

I should add that the current sentai season in Japan (due to end soon) is called “Kaitou Sentai Lupinranger VS Keisatsu Sentai Patranger” (aka Gentleman Thief Sentai Lupinranger VS Police Sentai Patranger). It actually features two opposing sentai teams of three members each, one a thief team, hence “Lupinranger,” a reference to the master thief of French literary fame, Arsene Lupin, whose “treasures” figure in the series, and the other a police team. Both teams see it as their job to keep Lupin’s treasures out of the hands of a steady stream of alien monsters. What’s significant about the series for me is that it stars Haruka Kudo as the female Lupin member, its Yellow Ranger. Kudo was a key member of my favorite J-pop group, Morning Musume, from 2011 to 2017, when she left to take this acting job. (I was upset when she left MM, but overjoyed when I learned why.) She’s not the first J-pop star I like to make this transition, but she’s the first from Morning Musume and the first to be cast in a sentai series, meaning she’s been involved in two of my all-time favorite Japanese pop culture phenomena.

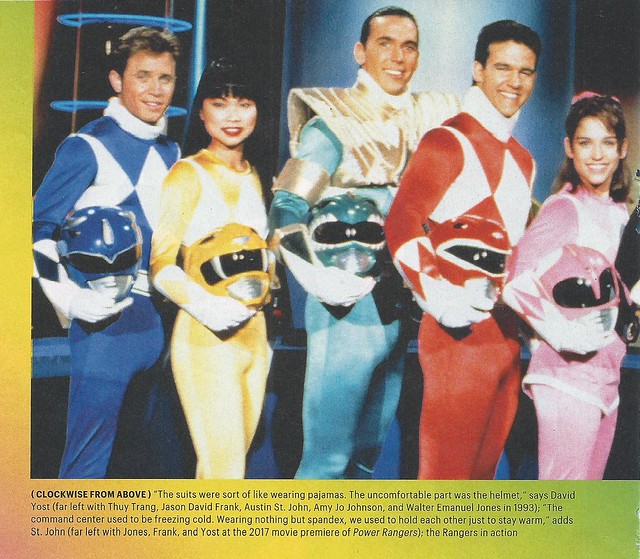

Finally, Entertainment Weekly did a 25th anniversary writeup on Power Rangers in their issue of November 30, 2018.

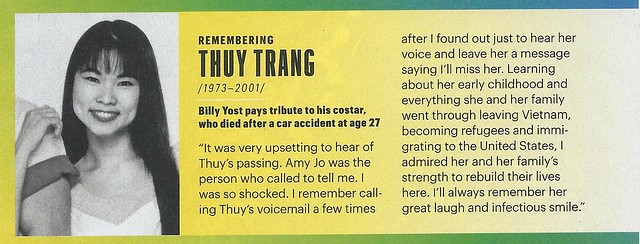

It ended with a tribute to Thuy Trang, who played Trini, the original Yellow Ranger, and who died in a car accident on September 3, 2001. I remember learning of this just a few months after it happened when I’d re-watched a few episodes of MMPR and consulted IMDB to see what Ms. Trang had been doing since. You can imagine the shock. I was absolutely devastated. Trang portrayed Trini as someone who cared deeply for the others, interacted warmly with them, and took great joy in their achievements. Here, EW reached out to David Yost (Billy) for a remembrance:

I didn’t even know that the Power Rangers was still going on as a series. What did you think about the Powers Rangers film that came out over a year ago? It was supposed to be a big deal, but seemed like it kind of flopped for some reason? Have you ever seen it? I also worked with the mother of one of the Power Rangers, and didn’t know until she mentioned that she had a son who played on the show. I wasn’t even into the show then, so it really meant nothing to me at the time, but having gotten into the show a decade ago, and done more reading up on the series—that got me more interested in it. Maybe you should just do a book about the entire series—you’re certainly got enough material for it!

I have most of the box sets of past seasons of PR, so I have a lot of catching up to do. I did see the big-budget Hollywood movie from two years ago and I had mixed feelings about it. It took a while to kick into gear, but it finally did and I enjoyed the last third very much. Good script and good cast, but it took 90 minutes for the teens to morph. I found the production design a little too dark for my tastes and the soundtrack a little too noisy. I have it on Blu-ray and will see it again soon. Thanks!