62 years ago today, on November 3, 1954, the Japanese monster movie, GOJIRA, premiered in Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda, the film established a whole new Japanese film genre, dubbed kaiju (giant monster). When the film was picked up by an American distributor, Joseph E. Levine’s Embassy Pictures, it was re-edited and partly dubbed in English, with new scenes added to it featuring an American actor (Raymond Burr) playing a reporter visiting Tokyo when the monster strikes, and retitled GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS for its April 1956 U.S. release. Godzilla became a worldwide phenomenon and more such films were made, 32 in all, several of which I’ve covered on this blog, including the very latest, SHIN GOJIRA (aka GODZILLA RESURGENCE), which was released this year.

Also on November 3, 1954, approximately 1300 miles to the southwest of Japan, in Taiwan, a baby girl was born and named Lin Ching-hsia. 19 years later, Ms. Lin would begin making movies in Taiwan, mostly romantic comedies and contemporary melodramas, with a brief trip to Hong Kong’s Shaw Bros. studio to appear in the leading male role of Jia Baoyu in the literary adaptation, DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER (1977). A few years later, she would return to Hong Kong to appear in Tsui Hark’s groundbreaking “wire-fu” fantasy adventure, ZU: WARRIORS OF THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN (1983), where she played a high-flying warrior priestess called the Countess who resides with her band of priestess followers on the title mountain, and her career took a whole new direction.

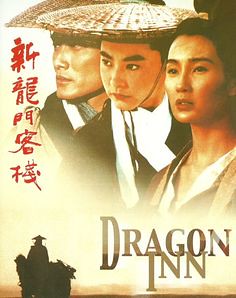

Under the name Brigitte Lin she became a star of period fantasies and action adventures that captivated audiences the world over, including Tsui Hark’s PEKING OPERA BLUES (1986), DRAGON INN (1992), SWORDSMAN II (1992), SWORDSMAN III: THE EAST IS RED (1993), THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR (1993), and two films by Wong Kar Wai, CHUNGKING EXPRESS and ASHES OF TIME, both 1994. She was quite busy for an eight-year period culminating in the production of six films a year from 1992-1994, following which she left the industry entirely to marry billionaire Michael Ying, the head of a clothing retail empire, and embark on a new life as a wife and mother.

I’ve been a big fan of Godzilla movies since I was a child and first saw GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS on television. I experienced a resurgence of interest in Godzilla movies when, in the early 1990s, I learned of an exciting new series of them being made in Japan but not being released in the U.S. I was visiting comics shows in search of anime VHS tapes from Japan around this time and the dealer I frequented the most also carried unsubtitled editions of the recent Godzilla movies. Eventually, I located fan-subbed copies (with English subtitles supplied by fans in the U.S.) and I began reveling in some of the best Godzilla movies ever made in a series that began in 1989 with GODZILLA VS. BIOLLANTE and continued with GODZILLA VS. KINGGHIDORAH, GODZILLA VS. MOTHRA, GODZILLA VS. MECHAGODZILLA, GODZILLA VS. SPACE GODZILLA and closing out in 1995 with GODZILLA VS. DESTOROYAH.

Also around this time I was discovering Hong Kong action films, many of the best of which starred Brigitte Lin, many of which I saw in theaters: DRAGON INN (my first visit to a Chinatown movie theater), PEKING OPERA BLUES, SWORDSMAN III: THE EAST IS RED, THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR, FIRE DRAGON, CHUNGKING EXPRESS and ASHES OF TIME. So the first half of the 1990s saw an increasing confluence of Brigitte Lin and Godzilla in my life.

I only realized this morning the November 3rd connection between these two cultural phenomena, so I haven’t had time to rewatch GOJIRA or any of Ms. Lin’s movies. Therefore I’m putting together a compilation of excerpts from previously written and previously published reviews. I’ve reviewed a number of Brigitte Lin movies on Amazon and IMDB, so I’ll include links and excerpts below.

As for Godzilla, you can easily find my other blog posts on these films by clicking the Godzilla tag at the end of the piece. However, since I’ve singled out the 1990s Godzilla films (commonly known as the Heisei Godzilla films) because they coincided with Brigitte Lin’s busiest period in Hong Kong cinema, I’d like to begin by posting an excerpt from an unpublished magazine article on these films that I wrote in 1996:

Fans of Godzilla, Japan’s firebreathing radioactive dinosaur, along with devotees of science fiction and monster movies in general, have in the last six years been denied the opportunity to see a series of the most exciting, imaginative and poetic monster movies in recent history. The last five Godzilla movies, made in the years 1991-1995, have seen no official release in the U.S. at all, while their immediate predecessor, made in 1989, saw very limited release. Two of these six movies–Godzilla vs. Mothra and Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla–are arguably among the best Japanese monster movies ever made.

The last Godzilla movie Americans saw in theaters was Godzilla 1985 (1985), a re-edit of the Japanese film, Godzilla 1984 (1984), featuring added American-made scenes with American actors, including Raymond Burr, who had been the star of American scenes added to the film that started it all, Godzilla (Japanese title: Gojira, 1954), released here in 1956 as Godzilla, King of the Monsters. The subsequent Godzilla film was Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989), which saw some release in the U.S. in an English-dubbed version distributed by HBO Video in partnership with Miramax and cablecast a handful of times on the HBO-owned cable channel Cinemax. The five subsequent Godzilla films–Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992), Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla (1993), Godzilla vs. Space Godzilla (1994), and Godzilla vs. Destroyer (1995)–remain unreleased in this country although high-quality bootleg copies with fan-created subtitles have been circulating among the sprawling underground network of japanese “kaiju” (monster) fans.

While the scripts and characterizations vary in quality from film to film, they all boast excellent photography and production values, expertly staged battle scenes, imaginative monster designs and special effects, and high caliber acting by performers who take their roles seriously no matter how outlandish the proceedings may get.

As a body of work these six films, known collectively as the Heisei Godzilla series, offer a consistently serious tone and realistic style, in contrast with some of the Godzilla films of the 1960s and ’70s and their fiendish alien villains, weather-beaten rubber suits, toy miniatures, and the monsters’ cartoonish gesticulations, such as Godzilla’s karate stance in Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973).

My Brigitte Lin fandom began when I saw one of her films for the first time on my first visit to a Chinatown movie theater, the old Sun Sing Theater on East Broadway in 1992, where DRAGON INN (1992) was playing on a double bill with the Jackie Chan action comedy, TWIN DRAGONS. New York was experiencing a renewed surge of interest in Hong Kong cinema and a film programmer named Peter Chow was curating series of these films at local rep houses, including the Cinema Village on 13th Street, where I saw PEKING OPERA BLUES, SWORDSMAN III: THE EAST IS RED, and THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR. I saw two other Brigitte films at Chinatown theaters during this period, FIRE DRAGON and ASHES OF TIME. I was also visiting video dealers for VHS tapes of other films of hers and amassed quite a collection.

In 2001, I started seeking out DVDs of previously unseen work of hers in Chinatown video stores and eventually discovered a cache of Ms. Lin’s early Taiwanese films on the cheaper VCD format (Video Compact Disc), the only format in which they were available, so I purchased a stack of those as well.

RUN LOVER RUN

RUN LOVER RUN (1976) was recommended to me by a friend (who’s seen PEKING OPERA BLUES well over 100 times) and it featured Lin as a perky college student and all-around athlete who pursues her interests in various sports and disdains all suitors, preferring “real men” like Charles Bronson and Steve McQueen, whose movie posters adorn her bedroom walls.

Here’s an excerpt from my IMDB review of the film:

RUN LOVER RUN features Lin as Li Ping, a tomboyish college athlete who specializes in track, mountain climbing, swimming and basketball, among other sports. She prefers the company of her male athlete classmates to that of any potential suitors. She resents the attempts of her meddling mother to marry her off and when an old family friend (Alan Tang) returns home from his studies in the U.S., Lin resists the efforts of their two families to bring them together. Instead, she hooks the young man up with the girlfriend of her brother, who’s away in the military. When that seems to work, it upsets everyone’s plans and makes Lin realize what a fool she’s been. Is it too late to set things straight?

The film is simple, direct and reasonably well-made. Brigitte cuts a striking, slender figure and is glimpsed in all manner of athletic activity and a variety of attractive costume changes (which help to distract from the god-awful 1970s men’s fashions on display). She is constantly in motion and functions, as she would in so many of her later films, as an irresistible force of nature. She’s cute and captivating and one can easily see here the budding form of the great screen beauty she’d become. Fans will recognize in Li Ping the seeds of all the dynamic qualities they’ve come to love in Lin’s later films. In fact, if Li Ping were to avoid marriage and simply continue developing her skills, gaining power, remaining forceful and never stopping, she’d become…Asia the Invincible!–to name Lin’s famous character from SWORDSMAN II and THE EAST IS RED.

An interesting twist for film buffs is the fact that Lin’s character is a big fan of American movie star Charles Bronson and has big posters of him (and his MAGNIFICENT SEVEN co-star Steve McQueen) on her wall. At one point she even shows Alan Tang the Bronson poster and declares to him that that’s her boyfriend, a “real man.” Tang later dresses up as Bronson and acts “rough” with Lin to teach her a lesson. (Interestingly, Ms. Lin and Mr. Bronson share a birthday, November 3rd.)

And here’s a link to another review of the film, this one by Brian Naas:

http://brns.com/pages3/comed46.html

POOR CHASERS

POOR CHASERS (1980) is a romantic melodrama with an element of class consciousness as Lin’s character tries to conceal her poverty-stricken background from a well-off boyfriend. Here’s what I wrote about it on IMDB:

This film starts out as a romantic comedy involving two sets of friends, a pair of college girls and a pair of male buddies from off campus. In its second half, however, it turns into a rather dour familial melodrama that dampens the considerable good spirits of the first half. Brigitte Lin and Chelsia Chan Chau Ha play two college girls who meet Charlie Chin and Alan Tam while playing tennis. The two male buddies pursue the girls with ardor, but no one matches up to anyone’s satisfaction. When Charlie makes clear to Chelsia that he loves Brigitte, it temporarily shatters the girls’ close friendship. Only when Brigitte promises to have no boyfriend before graduation do the girls patch up and then get revenge on the boys by trying to break up their friendship. Miraculously, through it all Brigitte and Charlie develop a genuine love for each other that gets tested severely when Brigitte’s mom meets Charlie’s father and tells the truth about her poor background in Taiwan after Brigitte had initially told Charlie that her mother lived in America. This sets into motion a chain of melodramatic events that threatens to upset all sorts of familial and budding romantic relationships.

It’s all very well acted and, despite the downbeat turn in its second half, well told. One of the film’s most endearing elements is the quality of the friendships. The two girls clearly enjoy their friendship even though Brigitte is the serious, more stable one, while Chelsia is the flightier, more flirty one. The two guys are very expressive and emotional in the way they interact with each other. An extra emotional layer is added with the fact of Brigitte’s poverty-stricken single parent household. Poignant flashbacks show her as a girl in grade school derided for bringing in a lunch box with left-over vegetables. The fact that she excelled at school and athletics and acquired affluent friends shows a character who overcame her disadvantaged background. Fans of Brigitte Lin will no doubt enjoy seeing another side of this versatile actress’s abilities. Some of her early Taiwanese films, such as this and RUN LOVER RUN (also reviewed on this site), are available on subtitled VCDs (video compact discs).

DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER

When Celestial Pictures started releasing new remastered DVD editions of films from the Shaw Bros. studio in 2002, I was astounded to find that one of them starred Brigitte Lin. It was a Huangmei Opera rendition of the classic Chinese literary text, DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER (1977), and Lin played the leading male role, the scion of a wealthy family in 18th century China who falls in love with his frail cousin (played by Sylvia Chang, a Taiwanese contemporary of Lin’s). When the family chooses another bride for him, it sets into motion a chain of turbulent events which end in tragedy for all. Lin and Chang give extraordinarily powerful performances, inserting psychological layers that were generally absent from films in this genre. It’s easily one of Lin’s best performances and one of the Shaw studio’s best films.

Here’s an excerpt from my IMDB review:

For this lavish 1977 Shaw Bros. adaptation of the classic Chinese novel, “The Dream of the Red Chamber,” director Li Han-hsiang (LOVE ETERNE) cast two young Taiwanese actresses in the central roles of young lovers Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu. Brigitte Lin, then a star of contemporary Taiwanese melodramas and romantic comedies and eight years away from the success she would have in Hong Kong films like PEKING OPERA BLUES, plays the male role of Baoyu, the young scion of the Jia household, while Sylvia Chang (a future star presence in Hong Kong cinema in her own right) plays the frail Daiyu, a cousin who has been sent to live in the house after the death of her mother. The two teen-age cousins are drawn to each other at first sight and, over the years, despite the family’s concerns, grow up and seek to marry. The female heads of the Jia household, led by Baoyu’s grandmother (Wang Lai), mother (Ouyang Shafei), and manipulative aunt (Hu Chin), prefer that Baoyu marry another, healthier cousin and set in motion a plot to deceive him into doing so. The almost arbitrary decision to thwart the two lovers results in tragedy and great upheaval for all.

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen two star performances quite like those delivered by Lin and Chang in this film. Some might consider such work overly melodramatic, but I would argue that the entire film is driven by the psychological states of the two lead characters. They exist on an entirely different emotional plane from the other characters and everything is experienced through their perceptions. No one else in the film can see or feel what passes between them. They move differently from the other characters in a genre (Huangmei Opera) that normally relies a great deal on characters’ stylized movements. They look out at the world differently. There are unforgettable closeups that convey multiple layers of psychic pain and loss. There is one chilling moment where the two gaze at each other across the chasms of madness, despair and grief and smile and slowly begin to laugh together while oblivious to anything or anyone else around them.

Both characters are completely at odds with the strictures of the setting and the customary behavior expected of them. Every move they make, every gesture, every expression is one of dissatisfaction and even defiance, although they act out these feelings in different ways. Baoyu is an impulsive free spirit who does what he wants (and gets brutally punished for it by his father in one scene). Daiyu withdraws into herself, crying frequently and adopting a private ritual of burying fallen flower petals, a practice mocked by the other maidens. The two quickly understand how completely in tune they are with each other. Almost the entire second half of the film is devoted to the grief, melancholy, and outrage fueled by the family’s ill-fated attempt to impose their will on Baoyu, with sad songs and dying laments on the soundtrack, creating a cinematic treatment of heartbreak as wrenching as any such treatment can be.

SWORDSMAN III: THE EAST IS RED

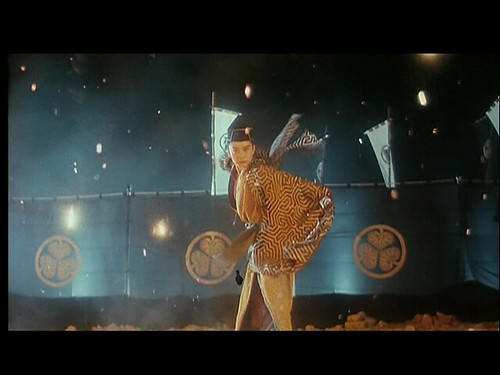

SWORDSMAN III: THE EAST IS RED (1993) followed SWORDSMAN II, which introduced Lin as Asia the Invincible, a young Chinese nobleman who uses mystical means to increase his martial arts power via a process that turns him into a woman. In this sequel, decades have passed and Asia the Invincible comes out of hiding to attack and destroy the numerous cults that have sprung up in her name since she’d disappeared. It’s one of my favorite Hong Kong movies.

Here’s an excerpt from my Amazon.com review:

THE EAST IS RED (1993), a sequel to SWORDSMAN II (1992), is the crowning achievement in the long career of Taiwan-born Hong Kong cinema diva Brigitte Lin (who retired a year later). She is at her highest-flying, gravity-defying best here as Asia the Invincible, a kung fu master who’d obtained the powers of the Sacred Scroll and changed from a man into a woman as a result. Here, four months after her “death” in Part II, she comes back on the scene with the help of a Chinese court officer monitoring transgressions by Spanish and Japanese warships, and seeks to root out the cults that have sprouted in her name and destroy the fake Asia the Invincibles who have emerged to run these cults. One of the fakes is Snow (Joey Wang), who’d been Asia’s lover when she’d been a man and who, we find, still loves the transformed Asia. Officer Koo (Yu Rongguang), watching these two beautiful women from the sidelines, gets mighty frustrated.

The film is shot through with the kind of grace and beauty that we only got in Hong Kong costume adventures. Every shot is gorgeous, every cut is perfect, every effect is breathtaking. The more fantastic the action, the more we suspend our disbelief, thanks to the ingenious staging and precision cutting. Characters never walk or take a boat when they can fly or run at high speed along the surface of the water. Characters rip the sails off ships and use them to fly through the air. Cannons are lifted as if they were rifles and ships are pushed back and forth by hand. Underneath it all is a deeply bitter romantic undercurrent. Never have I seen love, despair and rage so intertwined. Raw emotions propel the action and give a dreamy, delirious quality to the proceedings. Never has there been a Hong Kong film quite like this one and never will there be another one.

LAST STAR OF THE EAST

Finally, journalist Akiko Tetsuya interviewed Ms. Lin extensively after her retirement and then got the go-ahead to interview several of her colleagues in the Taiwan and Hong Kong film industries for a self-published biography of the actress entitled Last Star of the East: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia and Her Films (2005). Here’s an excerpt from my Amazon review:

Thanks to her persistence and sincerity, author Akiko Tetsuya, a Japanese journalist based in Los Angeles, managed to get a series of interviews with Lin over the course of five years. Lin was impressed with her and cleared the way for her to interview many of her friends and colleagues. Directors Tsui Hark, Ronny Yu, Stan Lai, Yim Ho and Wong Jing are among those interviewed, along with Tsui Hark’s wife, Nan Sun Shi; Taiwanese author Chiung Yao; production designer/editor William Cheung; photographer Yon Fan; and some of Brigitte’s longtime personal friends. In the course of these interviews we learn a great deal about Brigitte, her personal life, her work life and her relationships with friends and colleagues. We also learn a great deal about what movie production was like in Taiwan in the 1970s and early ’80s and Hong Kong in the 1980s and ’90s. We also learn what it’s like to be a movie star in Asia, where conditions differ significantly from those in Hollywood where stars are unusually driven and are granted extraordinary powers and privileges. Brigitte was an ordinary Taiwanese high school girl who became a movie star practically overnight without even seeking or desiring such stardom.

Leave a comment