I recently picked up a used 2-disc set containing THE FRENCH CONNECTION and various extras, including two documentaries on the film, deleted scenes, and separate audio commentaries by stars Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider and director William Friedkin. First, I re-watched the film for the first time since seeing it on cable sometime in the 1990s. I then went through all the extras. But before I get to my reevaluation, a little history is in order.

I originally saw THE FRENCH CONNECTION back in December 1971 during its initial theatrical release and then again a few months later in May 1972 when it was re-released on a double bill with another police drama from 20th Century Fox, THE DETECTIVE (1968), starring Frank Sinatra. At the time, THE FRENCH CONNECTION was a new kind of police thriller, tightly edited, leanly plotted, and offering gritty, grainy, street-level camerawork, shot entirely on location, much of it at night under low-light conditions and much of it with a handheld camera. The story, based on a real case, related a drug bust by NYPD narcotics agents working with Federal agencies that broke “the French Connection,” in which multiple kilos of heroin were smuggled in from Marseille every month to supply drug dealers in New York. The film follows the two NYPD detectives who first got wind of the lead that led to the bust, Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (pseudonyms for the actual detectives, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso), and we see them put a low-level mobster under surveillance in the hope, soon realized, that it will lead to the bigger fish involved in the operation. We see wire-tapping, surveillance, and lots of shoe leather and gasoline employed to follow the various suspects around the streets, hotels, subways and ungentrified outer-borough neighborhoods of New York. For the first time, we got extended looks at the less exciting aspects of police work, the painstaking drudgery involved in pursuing a case. Eventually they locate the stash of heroin and set up a mass arrest of the participants in the caper.

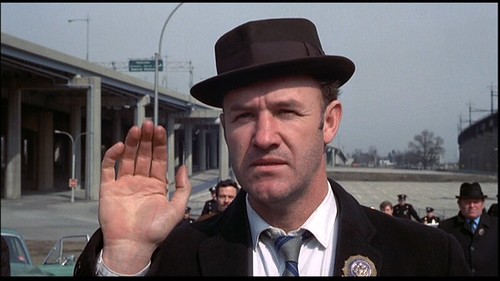

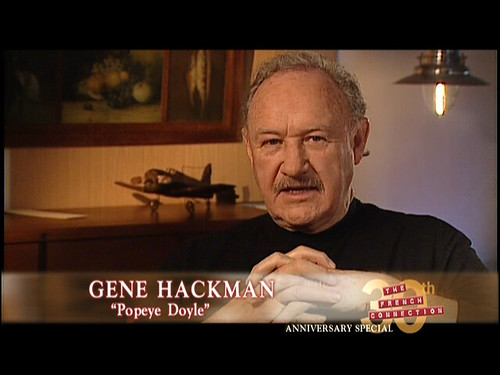

Unlike the successful cop thrillers immediately preceding this film, THE FRENCH CONNECTION was not about “cool” cop heroes like the protagonists of BULLITT (1968) and COOGAN’S BLUFF (1968) or even DIRTY HARRY, another 1971 release and directed, like COOGAN, by Don Siegel. It did not glamorize Doyle and Russo, nor did it cast the roles with movie stars like Steve McQueen (Bullitt) or Clint Eastwood (Coogan and Harry Callahan). It didn’t even go the route of THE DETECTIVE, with Sinatra, and MADIGAN, with Richard Widmark, both also 1968 and featuring old-school cop heroes who weren’t nearly as retrograde as Doyle. The stars of FRENCH CONNECTION, Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider, were working character actors with backgrounds in New York theatre, with Hackman having the higher profile thanks to character parts in BONNIE AND CLYDE, DOWNHILL RACER, THE GYPSY MOTHS, and a leading role in I NEVER SANG FOR MY FATHER. While few of the cop heroes of these years played it by the book or bothered with due process, Doyle seemed unusually brutal and abrasive and was not above using profanity and racial slurs, often quite casually. Russo’s role was to rein in Doyle’s excesses and play the good cop to his bad cop. Doyle is not a happy man, given his heavy drinking, sleeping in bars, and harassment of women. He seems incapable of normal human relations. When, in the finale, he mistakes a fellow agent for a suspect he’s pursuing and shoots him several times, he shows no remorse when he learns who he shot (and possibly killed—we never learn his fate). We’re not supposed to romanticize Doyle. Despite all this, Eddie Egan was quite pleased with Hackman’s portrayal.

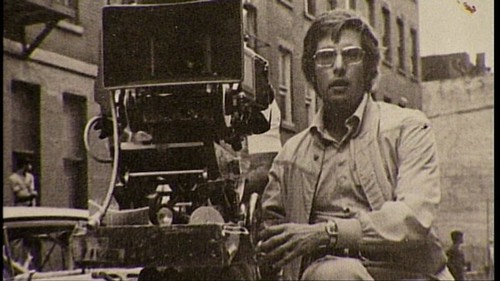

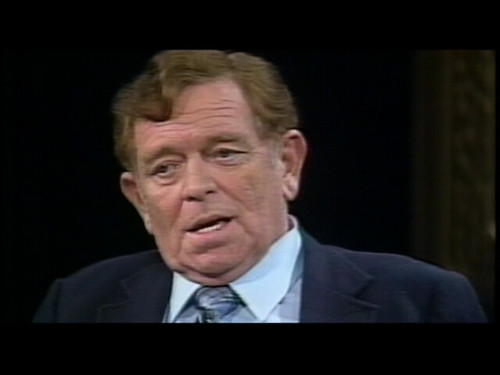

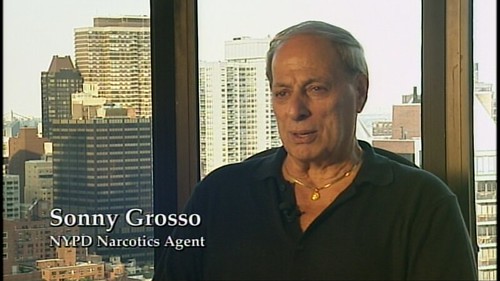

The film was directed by William Friedkin, a young filmmaker in his 30s who’d spent years in Chicago making documentaries and put that experience to use on this film. He was aided throughout the process by a close collaboration with Detectives Egan and Grosso, who served as technical consultants and also took parts in the film, Egan playing Doyle’s boss and Grosso playing a federal agent.

Eddie Egan:

Sonny Grosso:

The film’s innovative approach was enough to please critics looking for realism from a Hollywood studio system that was drowning in excess (HELLO, DOLLY!, anyone?) and threatened with bankruptcy, and enough to please Academy voters who awarded the film five Oscars (out of eight nominations): Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Hackman), Best Screenplay and Best Editing.

The film is a collection of great scenes, starting with the first scene to feature Doyle and Russo, with the two working undercover on a Brooklyn street where they roust a drug suspect (Alan Weeks), chase him into a vacant lot and arrest him for, among other things, “picking your feet in Poughkeepsie.” (Doyle is dressed as Santa Claus in the scene.) Later, we see the two, as plainclothesmen, bursting into a black bar, also in Brooklyn, where they make everyone present line up, as they’re quickly ridding themselves of drugs and contraband, and Doyle takes one of them into the bar’s bathroom, ostensibly to beat him, but actually to get information from the man, an undercover cop (Al Fann) embedded in the drug scene.

Some of the best scenes involve the team of detectives, Doyle, Russo, and two Feds, Mulderig (William Hickman) and Klein (Sonny Grosso), following the Frenchman, Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey), who is suspected of being the mastermind behind the smuggling operation, as he walks through Manhattan streets and into hotels and fancy restaurants, with one memorable bit showing Doyle and Russo freezing in the frigid New York winter of 1971 and eating cold pizza and drinking cold coffee while Charnier and his associate sit comfortably inside a French restaurant eating gourmet food. (It was reportedly below zero on the night they shot this scene.)

My favorite scene in the film at the time was a subway stalking scene where Doyle follows Charnier, dubbed “Frog 1,” into the Grand Central subway station and the platform for the Grand Central shuttle to Times Square. The two men jockey back and forth, getting on and off trains stopped in the station, one trying to lose the other while the other tries to hide the fact that he’s on the first one’s tail, with Frog 1 eventually outwitting Doyle and leaving him behind as the train speeds away.

An effective scene late in the film involves surveillance of a car driven by one of the suspects and left overnight on a deserted street in Lower Manhattan, believed by Doyle to be the transfer point for the drugs and expecting it to be picked up by others in the operation. They wait and wait and eventually, in the middle of the night, a group of shady characters descends on the vehicle and the police surround and arrest them, only to learn they’re lowly car thieves eager for the town car’s spare parts. Doyle is sure the car is “dirty” and has a police mechanic (Irving Abrahams, the actual mechanic who worked on the car) disassemble it to examine its every last nook until they find the heroin. Then they have to re-assemble the car in order to return it to its French owner and then follow it to its final destination on Ward’s Island where the exchange is to be made.

The one big setpiece that cemented THE FRENCH CONNECTION’s reputation as a crowd-pleaser was the inclusion of a spectacular chase scene that was meant to surpass the car chase down San Francisco’s steep streets in BULLITT. This time it’s a car chasing an elevated subway train, in a scene in which Doyle, in a commandeered car, pursues the French sniper who’d tried to kill him and eventually catches up with him when the train on which the sniper has escaped reaches the end of the line and smacks into another train. It’s quite a thrilling sequence and a masterpiece of action-film editing. It all looks as if they filmed it in actual traffic without blocking streets off. The fact that nothing quite like this happened in the real-life case didn’t seem to bother anyone back then. (More on all of this below.)

In re-watching it, I have to say that parts of the film held up very well, while the complete work itself was much less compelling than it once was. This time I realized just how thin the story was. Two detectives follow a lead and keep following and following until they find a car that is eventually revealed to contain drugs and then they arrest all the participants in the smuggling caper. That’s pretty much it. It initially worked because so much detail and character interaction were added to this slim framework, raw material that was far more authentic than anything we’d seen in police thrillers before. And it was all pretty much based on the actual facts. Except for one glaring sequence—that train-and-car chase.

With this viewing, I was quite annoyed at how little the chase sequence contributed to the narrative and how little sense it made. And it was entirely made up for the film. It begins when Nicoli (Marcel Bozzuffi), the hired assassin working for Charnier, tries to shoot Doyle with a rifle from the roof of a housing project in broad daylight. Why would a skilled French hitman put the whole operation in jeopardy by killing the detective investigating the case? He would have known that this would have increased the heat on the smugglers, not turned it down. International assassins don’t make those kinds of mistakes. And then he botches the job by missing his target!

The chase itself is quite ludicrous on its surface. Doyle runs up to the elevated subway platform and gets on the wrong side, where no people are visible, and hesitates too long before running back down and then up to the side where Nicoli is standing. He misses the train that Nicoli gets on and then runs down to the street to try and commandeer a car to chase the speeding train. The train has quite a head start by the time Doyle gets a car from a hapless citizen. Yet Doyle catches up and makes it to the next subway station in time to run up to the platform to greet the incoming train. Nicoli, by this time, has forced the motorman at gunpoint to skip the station, so Doyle runs back down, gets back into the car and proceeds to speed through traffic until he gets to the end of the line where the fleeing train has been stopped by another train on its track. He then confronts Nicoli as he leaves the train and stumbles down the steps.

I’m sorry. I just didn’t buy it this time. I know what traffic on these streets is like and there’s no way a random automobile could make it through as fast as a subway car. The absurdity here creates such a contrast with the realism of the preceding scenes that it just takes me out of the movie. (Friedkin addressed this issue in his commentary, which I’ll get to in a moment.)

Later, during the disassembling of the car to find the drugs, I watched as they tore it apart so thoroughly and irretrievably and realized they could never put it back together without the signs of wear and tear from the disassembling. Yet they do it in a matter of hours and return it to the Frenchman who claims ownership of the car without suspecting a thing. Again, I couldn’t buy it.

So I watched the documentaries and listened to the commentaries and read up a little on the case. The chase, of course, never happened. The closest thing in real life is when Egan lost Frog 1 on the shuttle platform and ran up to the street and implored Grosso to drive like hell to try and catch the Times Square shuttle at the other end, but that seems impossible given the slow pace of 42nd Street traffic and no one indicates that they ever managed to pick up the trail. Quite a big difference if you ask me.

In his audio commentary, Friedkin insists that the car could go 90 miles per hour while the subway train’s maximum speed is 50 miles per hour, so it was theoretically possible. I’m still not buying it. That might work if it was a clear path the entire way, but it certainly wasn’t in the film. Doyle’s car gets banged up quite a bit on the way. We learn from one of the documentaries that the stunt driver of the car, Bill Hickman, did indeed go at high speed through real traffic to get a lot of the footage used in the chase, but Hickman was an experienced race car driver while Eddie Egan was not and would not have been able to achieve the same results.

As for the car disassembling, Friedkin insists it happened that way, but everything else I’ve read and heard indicates that the car was taken apart at a much more leisurely pace well after the suspects were rounded up, so no one was expecting the car to be returned. Irving Abrahams is reported to have boasted to Friedkin that he and his crew could take a car apart and put it back together in perfect order in four hours, so Friedkin used that as the basis for the scene, not the actual facts of the case.

I will say that the subway stalking of Frog 1 on the Grand Central shuttle platform is still the most memorable scene for me, but for reasons that have more to do with changes in the landscape of the subway system in the years since. Part of the action shows Doyle and Charnier ordering drinks from a food stand that was situated on the platform adjacent to the train track. I remember that food stand and its equivalent on the Times Square side of the shuttle. I used to grab hot dogs and drinks and quick snacks there all the time. When I was coming home late from work or from a movie, it was a convenient place to grab something to eat before the long ride home to the Bronx. They offered hot dogs, French fries, knishes, coffee, soda, juice, salted snacks, sugary snacks, and even the candied apple Doyle buys and starts to eat in the scene. (I’ve never touched a candied apple in my life.) Those food stands were dismantled when some genius in either the Koch or Dinkins administration ordered that subway stations be “decluttered.”

We learn from the commentaries that this entire sequence was, like many of the location scenes in the film, “stolen,” meaning they did not get permission from the Mayor’s Office to shoot at these places, they just showed up with a crew and the principal actors and began shooting the action—in sequence. Detectives Egan and Grosso were on hand, along with other officers recruited to help with the production, in order to smooth things over in case any vigilant transit cops appeared to question the goings-on. Camera operator Enrique Bravo was pushed in a wheelchair with a handheld camera for any shots that required camera movement. Granted, we can tell the subway riders aren’t paid extras thanks to the way they frequently look at the camera. But in some shots, the passersby don’t look at all, which made me think initially that some extras were brought in, despite what the interviewers say.

But then there are plenty of shots like this:

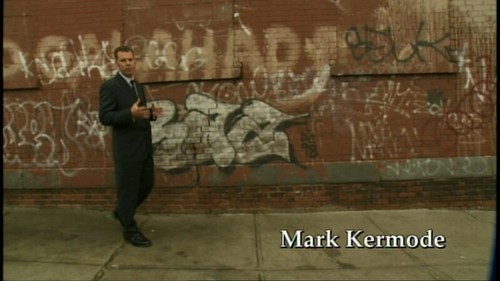

There are two documentaries in the DVD set, “Making the Connection: Untold Stories of ‘The French Connection’” and “Poughkeepsie Shuffle: Tracing the French Connection.” The first is a 30th anniversary production made in 2001, while the second is a BBC documentary made in 2000. Both interview a lot of the same people: Sonny Grosso, William Friedkin, cinematographer Owen Roizman, producer Phil D’Antoni, actors Hackman, Scheider and Tony Lo Bianco, and studio execs Richard Zanuck and David Brown (who were both ousted from Fox before the film was released). The first film adds author Robin Moore, who wrote the book about the case on which the film was based. (Eddie Egan had died in 1995.) The BBC film adds some key personnel to the list of interviewees: assistant director Terry Donnelly, sound recordist Chris Newman and NYPD narcotics agent Randy Jurgensen, who acted in the film, worked on the case and assisted Egan and Grosso on the set. Both films cover a lot of the same ground, but the BBC documentary, hosted and produced by Mark Kermode, is the better of the two, organizing its information much more efficiently and not cutting away before a story is finished.

Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider were both interviewed separately for audio tracks and their interviews, each running under 30 minutes, are used as audio commentaries on different portions of the film. Neither is scene-specific. Friedkin’s commentary, on a second track, covers the whole film and is quite scene-specific. He’s also not the most reliable narrator, as some of the conflicting interviews in the documentaries reveal.

The behind-the-scenes element revealed in this material that intrigues me the most is the level of involvement of Egan and Grosso in the making of the film. When the producers had finally gotten a screenplay they could work with (by Ernest Tidyman, author of the novel, “Shaft”), it was lean and straightforward but lacking the essence of the two detectives, so Friedkin set about adding to it with the help of the detectives. And when Hackman and Scheider began riding around in the police car at night with Egan and Grosso during pre-production and witnessing and participating in drug busts, they would describe what they saw and heard and all of that would be incorporated into the screenplay. When they actually started shooting the scenes, Egan and Grosso were always on set and frequently consulted beforehand to make sure the details in the scene were right. Hackman and Scheider were encouraged to improvise a lot and much of their dialogue is based on things they heard Egan and Grosso say, e.g. the whole “pick your feet in Poughkeepsie” routine. What other films exist where the true auteurs turn out to be the subjects of the film, doubling as technical advisors? Given the number of Oscars the film won, should not Egan and Grosso have been awarded in some way? Especially since the final screenplay, which won an Oscar, contained so much that Egan and Grosso had put into it.

The other fascinating element of all this is the tension that existed between Hackman and Egan. Hackman found both Egan and the character, as written, supremely distasteful and wasn’t sure he could summon up the anger and meanness needed to effectively convey what a relentless and obsessive cop Egan was. An avowed liberal who had previously held dim views of law enforcement officers as a class, Hackman would demand of Friedkin that they find a way to humanize Doyle and Friedkin would adamantly refuse. “He’s a monster!,” Friedkin would declare. “But he can’t be!” The first day of shooting was a disaster. It was the first scene in which we see Doyle and Russo, the one where they make the undercover arrest of the dealer (Alan Weeks) whom Doyle accuses of “picking your feet in Poughkeepsie.” They had to rough up poor Weeks and they just couldn’t do it. They hadn’t yet reached that point in developing their characters, so Friedkin and the producers resolved to come back to that scene. Eventually they reshot it after they’d done the rest of the film and by this point, the actors were so into their characters that they wrapped the production in one afternoon of shooting. (Friedkin insists that he did most shots in one or two takes, rarely doing more than three.)

I find it odd that Hackman had such trouble getting into his character in light of the fact that the film he was shooting when he was summoned to New York to interview for THE FRENCH CONNECTION had him playing a character not at all unlike Popeye Doyle. In CISCO PIKE (1971), Hackman plays a Los Angeles narcotics detective who steals a shipment of marijuana and prevails on the title character (played by Kris Kristofferson), a down-on-his-luck singer who’d once been busted for drugs by Hackman’s character, to sell the marijuana in L.A. in the course of a weekend and turn the money over to him on Monday morning. The detective has a meltdown late in the film that is quite startling and expertly played. If Hackman could create this character so convincingly, Doyle didn’t seem like such a stretch to me.

Gene Hackman shares a scene with Eddie Egan in THE FRENCH CONNECTION

In any event, it helped both Hackman and Scheider a great deal to go on those tours with Egan and Grosso, but even there, Hackman’s scruples sometimes got the best of him. In one bust, Hackman was the one who found the drugs that the suspect had hidden, yet when they booked the suspect, Hackman tried to take the heat off of him and expressed uncertainty about whether it was necessarily proof of the suspect’s guilt, since he had found the drugs. He simply didn’t want to be responsible for this person going to jail. Eventually, of course, once he got into the swing of his character he was able to put aside all his qualms and summon up both the full spectrum of Doyle’s psyche, making the character thoroughly believable and compelling, if not exactly likeable. Under Friedkin’s and Egan’s guidance, it was enough to win Hackman an Oscar against such competition as Peter Finch, George C. Scott, Walter Matthau and Topol. It’s also nice to hear on the commentaries just how well Hackman and Scheider got along, creating a camaraderie that is quite evident in every scene they had together.

Despite my quibbles about the chase scene and some of the liberties taken in the narrative, THE FRENCH CONNECTION remains arguably the most innovative and realistic of Hollywood police dramas and has probably not been equaled in the years since. Nothing I’ve seen in any of the TV police shows in the last 40 years comes close, although I’ve been told to seek out “The Wire” in order to change my mind.

Hey, I enjoyed reading this because I love THE FRENCH CONNECTION,both because it’s a true-blue groundbreaking classic, and because it’s really that damn good. I got the DVD some years ago (amazingly, as much as I loveU ’70s films, I had never actually seen the film until a decade ago,even though I saw it advertised as coming on TV years ago, but I didn’t manage to catch it.) And,yeah,the BBC documentary on the film was much better than the U.S. one—it was less flashy,, more low-key and informative. The film actually had a European approach to it. in its technique, so the way it show wasn’t anything new–this was just the first time it had been used in a major American film.

Some other good films that were clearly influenced by THE FRENCH CONNECTION are HIGH CRIME, an Italian take on drugs and crime, BUSTED and THE NEW CENTURIONS. There’s also the early ’70s TV drama POLICE STORY and its British counterpart, the mid-’70s TV cop drama THE SWEENEY, who both did for cops on TV what TFC did for the image of cops in film—changed it completely. and made it much more realistic. The film THE SEVEN=UPS was supposed to be a follow-up to TFC, but wasn’t referred to as a sequel for legal reasons–which is too bad, since it features some of the same actors from TFC., and with the same producer, who also directed it. Now that one would be worth a write-up, since it’s so much like TFC.

What a visual feast. The actual plot is pretty goofy: fancy French guy hides cocaine in his fancy car to make the drug deal of the century. The characters and dialogue are both fairly cookie cutter too. But the action, the composition, the energy is all spot on. I would definitely see this again and again.

Great article! I just rewatched the film for the first time in 49 years – since its theatrical release. Your piece answers some questions I had and amplifies a lot of the concerns I had seeing it again after all these years (like did the mechanic really put the car back together again??). Nice job!

I agree that the realism is compelling, and the subway shuttle scene is hilarious. I find the sniper bit weird. 1) How do you get a sniper rifle (there was no case) onto the roof in a projects without anyone noticing and calling 911? 2) how do you miss at such close range? 3) the sniper wouldn’t take the shot until Doyle turned and was walking toward him 4) why abandon your rifle? 5) sniper would also have a pistol on him and could wait for Doyle and shoot him up. but mostly 6) Frog 1 knew he was tailed, but how would he know which cop it was??? it’s not like Doyle gave him a card

7) Doyle was in the snipers field of view for about 3 seconds. not enough time to acquire the target unless he knew that Doyle was turning the corner (he would need X-ray vision for that) 8) after shooting a cop and a conductor on the train, the sniper dropped his pistol AND LEFT IT there. why did he bother running from Doyle

&&&

I’m like daddy in this way: after the chase, I wanted to see the car returned to its owner. Instead they went from killing an unarmed man in broad daylight to Doyle in a car with his partner following somebody

I don’t see how they would have stashed 120 lb of heroin in the rocker panels. It just seems like too much heroin and two small rocker panels