This entry is part of the 1947 Blogathon sponsored by Shadows and Satin and Speakeasy. I chose two films from 1947 to write about and my original plan was to do separate entries on them, but after watching them back-to-back, I realized that the contrasts between them were so interesting that I thought it best to do a comparison piece. The first is ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY, Akira Kurosawa’s incisive portrait of postwar lovers in Tokyo caught up in a cycle of poverty, and I chose it because it was a Kurosawa film that I’d never seen before and this would be a good opportunity to finally see it.

The second is VIOLENCE, a low-budget melodrama from Monogram Pictures about an organization exploiting war veterans for power and profit, and I chose it because it was the closest thing I could find to a conspiracy thriller from 1947, a year filled with events in the U.S. that fueled so many conspiracy theories for years to come.

One film was made in a country recovering slowly from defeat and the ravages of war, while the other was made in a country flush with the glory of victory and newly emergent on the global stage as the dominant world power, yet the stories they tell offer a reversal of sorts.

In 1947, Japan was still in the early stages of rebuilding itself after the ravages of war and the bombing of many of its key cities. Much of Tokyo was in ruins and the survivors had to struggle for food, shelter and necessities. Civil society had to refashion itself under the watchful eyes of the American Occupation Forces, commanded by General Douglas A. MacArthur. A populace that had been exhorted by a fascist military government to sacrifice everything and die for their country was now feeling the shame and humiliation of being a defeated and occupied nation. After ninety years of an accelerated pace of modernization and industrial advancement, this was what they had to show for it. Gangsters and black marketers were the only ones who thrived, which made things hard for two honest people like the main characters of ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY.

ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY, released in Japan on June 25, 1947, tells what seems to be a simple tale of a young couple in Tokyo eager to spend their one free day of the week with each other despite the fact that they have so little money between them (35 yen). In the course of their day together, however, we get a steady stream of mood changes and emotional highs and lows, all set against a backdrop of Japan in the immediate postwar era as people tried to conduct normal lives while struggling to survive. The man, Yuzo (Isao Numasaki), a war veteran, is deeply depressed and doubtful about the chances of ever improving his lot. His girlfriend, Masako (Chieko Nakakita), is a perennial dreamer, always hopeful and optimistic and eager to put the best face on things. Yet as the day’s events both lift them and batter them, Masako falls prey to despair and tears, while Yuzo manages to get some of his old pre-war spirit back. The two shift moods and positions at several key points, each ultimately supporting the other and displaying the resilience that the Japanese needed to get through the postwar recovery. It’s a sad film in parts, but filled with moments of buoyancy and promise, and it brings to vivid life for us the everyday reality of Japan in 1947.

In the U.S. in 1947, returning veterans, having won the world war, were getting their old jobs back, going to school on the G.I. Bill, and starting families. A positive spin on the experiences of returning vets could be found in William Wyler’s epic drama, THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, the Oscar-winning Best Picture of 1946. But all kinds of tensions were simmering under the surface, many of them reflected in films coming out of Hollywood that would later be dubbed film noir by French critics (and 1947 was a prime year for film noir). There were labor troubles, including a bitter strike at Hollywood studios in 1946 and a sense that American Communists were behind a lot of labor agitation. This led to hearings staged in Washington in October 1947 by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (or HUAC), eager to investigate Communist influence in Hollywood. The hearings were filmed by newsreel cameras and Hollywood offered up numerous “friendly witnesses,” including such big names as Gary Cooper, Robert Taylor, Jack Warner, and Walt Disney, to promote Hollywood’s commitment to “Americanism” and counter the testimony of the ten “unfriendly witnesses,” leftist screenwriters and directors who refused to answer whether they were members of the Communist Party or not, a tactic based on their contention that the Committee had no right to ask such a question. This tactic backfired and the “Hollywood Ten” became the first studio employees to be subjected to the Hollywood blacklist, which would expand to include dozens more in the 1950s.

Also in 1947, sightings of Unidentified Flying Objects became common, leading one pilot, Kenneth Arnold, who saw these craft on June 24, 1947, to describe them as “flying saucers,” the first such usage of that term. One such object may have crashed in Roswell, New Mexico on July 2, 1947, attracting the attention of local ranchers who spotted and collected the strange debris. Something had crashed and the U.S. Air Force sent crews to clear the wreckage, prompting a press release on July 8 declaring that a craft from outer space had indeed crashed. The story was quickly retracted and replaced with another one insisting that a weather balloon had fallen from the sky and created the debris. Thus began the strictly-held official government policy, persisting to this day, of denying the possibility of extraterrestrial craft in our skies and covering up any possible evidence of such existence.

Also, on July 26, 1947, President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act into United States law, creating the Central Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the National Security Council. This created the “National Security State” about which so many commentators and civil libertarians have warned us in the decades since. The CIA has certainly been at the heart of many conspiracy theories. This was also, in no small way, the beginning of the Cold War.

VIOLENCE, directed by Jack Bernhard and released in the U.S. on May 9, 1947, is set against the backdrop of an organization in Los Angeles called United Defenders, set up by a man named True Dawson (Emory Parnell), whose ostensible aim is to advocate on behalf of war veterans for housing and jobs, but is really intent on stirring up trouble between labor and management in order to collect hefty paychecks from corporations by suppressing labor unrest. When Ann Mason (Nancy Coleman), an investigative reporter working undercover as Dawson’s secretary, attempts to get her exposé of United Defenders out, she is injured in an accident while fleeing someone following her and winds up with amnesia. She goes back to work for Dawson with the help of Steve Fuller (Michael O’Shea), a war veteran seeking to gain entry to United Defenders, who then gets hired by the organization also.

Nancy Coleman, Sheldon Leonard, Michael O’Shea in VIOLENCE

Fuller is actually an undercover government agent investigating the organization as well, including the facts behind a murder carried out by one of Dawson’s enforcers. Fuller confides in Ann, who is still confused from the amnesia, and she then betrays Fuller to Dawson and his chief enforcer, Fred Stalk (Sheldon Leonard). When Ann finally comes out of her amnesia and remembers who she’s really working for, she seeks to set things right.

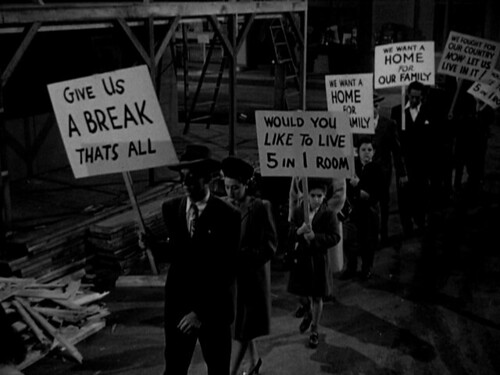

In the course of it, she and Fuller manage to intervene at a picket line where Dawson’s thugs plan to beat up war vets marching for affordable housing. The pair’s aim is to then locate the elusive “Mr. X,” a local power broker who’s secretly funding Dawson’s activities.

ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY focuses on short vignettes that make up the couple’s long Sunday together. We see them visit a model home under construction, one that’s way out of their price range. They then go to inspect a room for rent that they’ve heard about. We see Yuzo pick up a bat and join a boys’ baseball game, the first time in the film where we see him break out of his slump.

We see him visit a cabaret, while Masako waits outside, in the hopes of reconnecting with the owner, a war buddy of his. The manager treats him like a bum and gives him a meal, a beer and an envelope of money, while refusing to let him see his friend. Yuzo, his pride hurt, touches none of it and leaves in indignation. The couple then has an encounter with a hungry boy and share a rice ball with him. They go to the zoo. It rains. They decide to go to a concert they see advertised on a flyer (Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony”) and race to the concert hall in hopes of getting affordable “B” tickets. Scalpers buy up all the B tickets and price them out of the couple’s range. Yuzo attacks one of the scalpers but is beaten up for his trouble.

The couple winds up in Yuzo’s apartment. Yuzo stares out into space, in deep despair. Masako tries to cheer him up, but nothing will work. Finally, he grabs her and tries to force himself on her and she gets up and runs out. He lies there motionless for a long stretch until she finally comes back. By then her mood has soured also and she starts to sob uncontrollably. The shoe’s on the other foot now and he tries to cheer her up. The sun comes out and he suggests they go back outside. They get cheated on their bill at a local coffee shop—a drop of milk doubles the price—and they don’t have enough to pay, so he leaves them his coat along with their last 20 yen. The incident sparks up his old dream of running a café with Masako, “the Hyacinth Café.” On the site of a building ruin, they act out what the café will look like and what features it will have. When a crowd of curious onlookers forms, they run away.

Their next stop is an empty amphitheater. They get the idea to stage their own version of the “Unfinished Symphony,” with Yuzo conducting an imaginary orchestra and Masako in the audience “listening” and applauding. It takes a while for Yuzo to finally get started and it requires Masako to implore the “audience” (us), in a closeup in which she’s looking just below the camera lens, to clap and cheer him on. It’s a real Peter Pan/Tinker Bell moment and I can’t imagine an audience at a revival theater showing of this not responding. (According to Kurosawa, the Japanese audience in 1947 did not. He called it a failed experiment.) Through it all, we hear Schubert’s symphony on the soundtrack.

What makes all this work is the sincerity of the performers and the authenticity of the settings. Scenes play out in real time, such as the long, slow, quiet scene in Yuzo’s apartment where he finally pours out his frustration. The characters are given time to do everything their characters would do in such situations. There’s no quick cutting to speed things up.

Also, while some key sequences are shot in studio sets, much of the film is shot on location, some of it with hidden cameras. There is an incredible tracking shot of the couple as they race to make the concert on time through the streets of Tokyo, all shot from a moving car.

In his memoir, Something Like an Autobiography, Kurosawa describes the shoot:

“The leads in One Wonderful Sunday were Numasaki [Isao] and Nakakita Chieko, both of whom were still unknowns at the time. In order to do city location shooting, all we had to do was disguise the camera; no one recognized the actors’ faces. For these hidden-camera location sequences, we put the camera in a box, which was in turn wrapped in a carrying cloth that had only a hole for the lens to poke through. This could then be hand-carried….

“Numasaki wore a baggy suit and a military overcoat, and Nakakita an oversized raincoat and the kind of scarf you might see anywhere, so you certainly couldn’t say they stood out in a crowd. In fact, they blended in so well with the throngs of other couples in the same kind of drab attire that both the cameraman and I lost track of them any number of times. The story called for them to be the kind of young couple you might see anywhere in Japan at that time, so in that sense they were perfect for the parts. And for that reason they seem to me, as I think about them today, to be like a couple I met by chance right after the war in Shinjuku, talked with and became friends with, rather than protagonists of a movie.”

Like other Kurosawa films of the postwar era, DRUNKEN ANGEL and STRAY DOG, we get a rich view of life in Tokyo in the immediate aftermath of the war. The only thing missing in these films is any view of American soldiers or Occupation authorities, something the censors may have insisted on omitting. Too bad. That would have made the films even more authentic.

VIOLENCE is shot almost entirely on cramped studio sets with only a few visible shots of L.A. streets that were probably taken from other movies. The convoluted plot doesn’t make a lot of sense and characters tend to behave rather foolishly and recklessly. The undercover operatives leave all kinds of paper trails that would reveal their identities right away if they had smarter opponents. In fact, at one point, one of the opponents, Stalk, played by Sheldon Leonard in full gangster mode, does show some smarts and calls up Ann Mason’s magazine office in Chicago, after the exposé has been published (under a different byline), and asks them for information that would confirm the fact that she’s working for them and the office secretary happily provides it! One of the dumbest plot developments comes early on when Fuller, in the act of following Ann from the Chicago train station, orders his cab to follow her cab, thus prompting her to order her driver to speed up only for him to lose control and crash, causing the head injury that leads to Ann’s amnesia. The second driver’s response? “Quite a mess, hey Mister?” Not a shred of remorse on his part over causing the crash and not a shred of self-disgust on Fuller’s part for botching his own mission.

The crime movie melodramatics blunt any message that might have been derived from an honest examination of hate groups or political chicanery involving veterans or labor. (An exposé of dirty tactics on either side in any labor struggle of the period, particularly Hollywood in 1946, would have been most revealing if any filmmaker had had the courage to tackle it.) One scene where True Dawson implores the assembled veterans to join United Defenders stands out because it actually shows a counter-argument made by one veteran who accuses Dawson of using hate and high-pressure tactics that can only lead to violence. This same dissenter (played by Richard Irving) later shows up at the housing rally on the site of a proposed commercial building and speaks on behalf of affordable housing for veterans. The speeches tend to be filled with platitudes and are short on specifics, so it’s hard to figure out what real-life struggles were being referenced here. And, typical of the script’s hamfisted plotting, after all the denouncing of violence by the dissenter and the intervention of the good guys in the hopes of thwarting a riot by Dawson’s thugs, it all devolves into a vicious brawl anyway, despite the fact that the protesting veterans brought their wives and children to the rally.

I’m not sure if United Defenders was based on any actual veterans organization or hate group, although another film from that period, JIGSAW (1949), dealt with some kind of extremist/fascist group in New York. And there is a hint of foreshadowing in THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, a year before VIOLENCE, when a customer at the store where Fred Derry, one of the lead veteran characters, works starts making comments about the war and who we really should have fought (the Reds, not the Nazis) and exclaiming “good old-fashioned Americanism,” sounding somewhat like True Dawson. His words so infuriate Homer, a wounded veteran with metal claws in place of the hands he lost in the war and one of the film’s protagonists, that he assaults the customer and uses his claw to pluck the American Flag pin from the customer’s lapel. In any event, I’m not quite sure what the political leanings of the VIOLENCE filmmakers are. Were any of them leftists? Would any be blacklisted? Stanley Rubin, co-screenwriter, had a long and prolific career right through the blacklist era, while the other writer, Lewis Lantz, had only one credit after that and it came some 15 years later. The director, Jack Bernhard, ended his Hollywood career in 1950 but lived another 47 years. I’ve never seen either name on any list of blacklistees, but it’s been a long time since I’ve researched that period. I asked my friend Ed Rampell, a journalist in L.A. who’s written extensively about the blacklist period, about this and here is his response:

“According to Dave Wagner and Paul Buhle’s “Blacklisted, The Film Lover’s Guide to the Hollywood Blacklist” screenwriter Stanley Rubin had been a member of the CPUSA and “became an early friendly witness to save his career, but not without regrets or later efforts to make up for his sins to some blacklistees.” The authors believe the subversive group in “Violence” are “most likely fascists of some stripes” – not Reds.”

Still, certain elements in VIOLENCE look forward to later conspiracy films coming out of Hollywood, most notably the notion of a shadowy figure behind the operation (and he is indeed called “Mr. X” in this film) and the idea that he represents commercial interests eager to keep working people at each other’s throats. Also, the tactics used by United Defenders look and sound remarkably like those used by the Communist Party in I WAS A COMMUNIST FOR THE FBI (1951), which I wrote about here in the Frank Lovejoy Centennial piece on March 28, 2012. It also looks forward to Roger Corman’s THE INTRUDER (1962), which I wrote about here on May 14, 2012, and the tactics employed by a racist agent provocateur played by William Shatner to keep integration from proceeding forward in a southern town that’s been subject to a court order. Although the 1970s is considered the prime decade for conspiracy thrillers, thanks to such high-profile films as EXECUTIVE ACTION, CHINATOWN, THE PARALLAX VIEW, ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN, NETWORK, and WINTER KILLS, to name a few, the 1950s had its own unique brand of conspiracies in the numerous anti-communist thrillers of the era and the various alien invasion scenarios where invaders from other planets took over human minds and bodies or just intervened in human affairs for various reasons, something we saw in THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL, IT CAME FROM OUTER SPACE, INVADERS FROM MARS, THIS ISLAND EARTH, EARTH VS. THE FLYING SAUCERS, IT CONQUERED THE WORLD, INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS, PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE, and I MARRIED A MONSTER FROM OUTER SPACE, to name a few.

What’s interesting to me about seeing both ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY and VIOLENCE back-to-back is that the Japanese film, made amidst extraordinary hardships by a defeated nation, represents hope, resilience and optimism for the future, while VIOLENCE, made by a victorious world power, unquestionably the most powerful nation in the world at that moment, and one which suffered little actual damage in its homeland, is filled with anger, deception, betrayal, conflict, violence and a somewhat jaundiced view of civil society. In both films, the male protagonist is a war veteran, each having fought, of course, on the opposing side. While ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY shows an authentic snapshot of life for ordinary people in Japan in 1947, I’m not so sure that VIOLENCE comes even close to anything similar for the American people in 1947. Stylistically, VIOLENCE resembles film noir more than anything else, although I’ve never seen it listed in any film books covering noir. ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY, on the other hand, evokes Italian neo-realism and is seen by some as a Japanese counterpart of that cinematic movement, although its Capraesque qualities might disqualify such a label. There is indeed, some resemblance to Capra’s IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (1946), and not just in its title. (Coincidentally, the Capra film featured Sheldon Leonard in its cast.)

For the record, I watched ONE WONDERFUL SUNDAY on a DVD from Criterion’s “Postwar Kurosawa” set and I watched VIOLENCE on a Warner Archive DVD.

I really enjoyed the contrast between the two post war worlds! Great analysis, Kurosawa’s film sounds fantastic!

I agree with Summer Reeves. The way you’ve presented both films, made in opposing countries and just after WWII, is brilliant. Despite its flaws, Violence does sound intriguing. But I am really keen to see One Wonderful Sunday. I see you watched it via Criterion, but I’m going to try to find a semi-decent version for streaming online.

Thanks for this thoughtful post and for the introduction to these two films.

Thanks to you and Summer Reeves for your kind remarks. The more I think about the Kurosawa film, the more connections I see between it and IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE. George Bailey reaches his lowest ebb when he sees a vision of the world as if he’d never been born, while Yuzo feels like he doesn’t belong in the world at all, that there’s no place for him. Only after that are both protagonists able to appreciate what they’ve got. They experience similar emotional highs, but have had to truly earn them by going through such despairing low points.

Brilliant idea for the focus on 1947.

“One Sunday Afternoon” breaks my heart.

I want to check out “Violence”. Another returning vets film from 1946, “Till the End of Time” (in a small way) a group like United Defenders. A bar fight ensues between the veterans the audience has been following with some loud mouth recruiters for the group. It would appear such organizations were prevalent.

I’d completely forgotten about TILL THE END OF TIME, so thanks for reminding me. As I recall the scene, the vets, including Robert Mitchum, are in a pinball arcade and one of their group is a black vet who’s still in uniform and the bigot comes in to push his organization and somehow makes it clear that blacks and Jews will be excluded and that sets Mitchum off.

Really nice choices and enjoyed the connections you made between the postwar attitudes and views they depict. Well done and thanks for joining us for the blogathon!