Orson Welles would have turned 100 today, May 6, 2015. Last night I re-watched ORSON WELLES: THE ONE-MAN BAND, a 1995 documentary which shows Oja Kodar (Welles’ companion for the last 20-odd years of his life) going through film footage Welles left in numerous film cans (mostly 35mm) in storage over the years and sharing bits and pieces of it with us. While there’s little in the way of a potential masterpiece excerpted in it (other than, perhaps, THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND, his famous late unfinished project, and an arty made-for-TV short version of “Merchant of Venice”), it’s fun watching Welles in a variety of eras and boasting a variety of looks, mainly having fun with the camera. He loved filmmaking and liked to shoot wherever he went. As Kodar shows us, he carried a case with an editing console and another one with various cameras and filmmaking tools wherever he went. If you love Welles, you should see this film because there’s a lot of Welles in it, in all sorts of modes, and Kodar’s love and devotion to him are quite evident throughout.

I also watched the episodes Welles made for a BBC documentary series called “Around the World with Orson Welles” (1955), in which he goes to France, England, Spain and Basque country on the Spain-France border for delightful little human interest stories, including an interview with Isadora Duncan’s brother, Raymond, who lived in France and promoted a lifestyle based on possessing only what you could make yourself and not needing anything else. (He’s interviewed while adorned in his own handmade clothing.)

Each of the five episodes is enjoyable, but I especially want to recommend the two parts devoted to Basque country on the border between Spain and France. These are wonderful examples of the art form known as the film essay and reflect Welles’ deep and abiding love of humanity, a feeling that imbues all of his films. The Basque essays can be found on YouTube and I recommend that all Welles fans seek them out.

Welles directed a lot, even if most of it didn’t wind up on the big screen (or even on the small screen). And he appeared in a lot of work, both for TV and movies. Whatever he did was made more interesting simply because he was involved. And a lot of wonderful Welles material is available on YouTube these days.

I’m not sure how I first became aware of Welles. When I was a budding film buff, he was mostly known as an outsized character actor. I’m guessing my earliest glimpses of Welles were trailers for the films LAFAYETTE (1963), in which he played Benjamin Franklin, and THE V.I.P.S (1963) in which he plays a European film director stuck at an airport with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Around that time, I first became aware of CITIZEN KANE (1941), Welles’ most famous film and the one that marked his Hollywood debut, not only as an actor, but as a writer and director as well. This film was featured prominently in two books I pored through at the Tremont Branch of the New York Public Library, A Pictorial History of the Talkies, by Daniel C. Blum, and American Movies, by William K. Everson.

I believe the first film appearance of Welles I was exposed to was the James Bond parody, CASINO ROYALE (1967), in which Welles played the ostensible villain, Le Chiffre. I saw it on the big screen in late 1967 and, while the film itself was something of a mess, I was grateful for the opportunity to see so much venerable star power in one film: Welles, Peter Sellers, David Niven, Charles Boyer, William Holden, Deborah Kerr, John Huston, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and George Raft, not to mention up-and-coming comedy star Woody Allen.

Less than three years later, during the summer before my senior year of high school, I got to see CITIZEN KANE at a free screening at Columbia University, an event which my mother had heard about and urged me to attend. Needless to say, I was grateful for the opportunity to see a film often acclaimed as the greatest Hollywood film ever made, a consensus others may not share, but one I have no problem with. I would see it on the big screen many more times including at the New Yorker Theater on Saturday July 21, 1973, when it played on a double bill with Jean Renoir’s GRAND ILLUSION. It was on my way home on the subway from that screening, while thumbing through the afternoon edition of the New York Post, that I learned about the death of Bruce Lee the day before in Hong Kong (something I wrote about here on July 20, 2013). Nearly 20 years later, in 1991, on the occasion of KANE’s 50th anniversary, I saw it at the Biograph Theater on 57th Street in Manhattan and took a walk afterwards to try to find the address, 185 West 74th Street, where Charles Foster Kane visits Suzan Alexander and eventually sets up a “love nest” there, the discovery of which, by his political rival, precipitates his defeat in the race for Governor of New York (“Fraud at Polls,” the Kane newspaper declares). The address didn’t exist and I don’t believe it ever did, but the walk prompted an essay, which led to a series of essays based on walks around Manhattan, some of which I’ve been meaning to post here.

In any event, after that first screening of CITIZEN KANE in 1970, I eventually caught up with most of Welles’ other directorial efforts at repertory theaters in the city or on television, as well as many of his acting jobs. I was at a screening of Welles’ films at the old Carnegie Hall Cinema (I’m guessing it was a double bill of CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT and THE IMMORTAL STORY), when I overheard some film buffs discussing Welles’ films and one of them declaring that “Welles made four masterpieces–” before getting interrupted by one of the others quickly asserting his four chosen titles, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, LADY FROM SHANGHAI, TOUCH OF EVIL and MR. ARKADIN, pointedly omitting CITIZEN KANE. Oh, how cool it was for auteurists to dismiss CITIZEN KANE once upon a time.

In film school, Welles was like a god to us. He got the third American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award (after John Ford and James Cagney) in 1975, while I was still a film student, and we all watched the ceremony on TV and discussed it the next day. There were clips from THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND shown and it was everybody’s first inkling that he had another major fiction feature coming. (Sadly, we’re still waiting for it 40 years later.) One of our teachers at Hunter College, Barbara Leaming, even wrote a biography of Welles and was with him the night he died. I remember hearing the report about his death on the radio (he died October 10, 1985) and sitting down and crying. For all those years we’d hoped we’d see more films by him.

Welles’ acceptance of the AFI Lifetime Achievement Award:

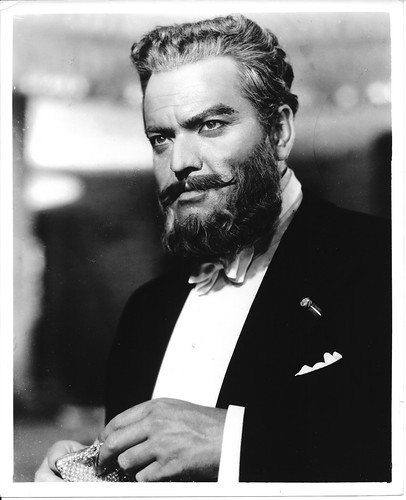

My favorite Welles performances in films he didn’t direct are JANE EYRE (1944), in which he played Rochester; BLACK MAGIC (1949), in which he played the notorious 18th century occultist Cagliostro; and PRINCE OF FOXES (1949), in which he played Cesare Borgia opposite Tyrone Power. The latter two were both shot on location in Italy and I believe Welles used the time there to shoot scenes for his long-in-production version of OTHELLO. JANE EYRE is the only one of the three I’ve seen recently and it’s such a beautiful and artful literary adaptation, with a dramatic score by Bernard Herrmann, that people often think that Welles had something to do with its direction, which is credited to Robert Stevenson, who had a long, respectable and productive career but did nothing quite as good as JANE EYRE before or since. Welles is thought to have directed much of BLACK MAGIC, which is credited to Gregory Ratoff, although I remember reading an interview with screenwriter Charles Bennett (published, I believe, in Film Comment) in which Bennett claims credit for finishing the direction of that film and Welles promising to “be a good soldier.”

Welles, right, as Cagliostro, with Akim Tamiroff in BLACK MAGIC (1949)

Tyrone Power, Orson Welles in Henry King’s PRINCE OF FOXES (1949)

But it’s always great to catch Welles in pretty much anything he did, especially the not-so-grand costume epics he sometimes did, like THE BLACK ROSE (1950), in which he played a Mongolian general in the 13th century, again opposite Tyrone Power, and THE TARTARS (1961), in which he plays a Tartar chieftain in the 10th century, this time opposite Victor Mature. Later on, in MARCO THE MAGNIFICENT (1965), Welles is demoted to the role of Marco Polo’s tutor, while Anthony Quinn plays Kublai Khan. In DAVID AND GOLIATH, an Italian biblical spectacle, Welles plays King Saul. In Robert Siodmak’s THE LAST ROMAN (1968), a West German-Italian-Romanian co-production, he plays Emperor Justinian in 6th century Constantinople. In the Italian western, TEPEPA (aka BLOOD AND GUNS, 1969), he plays a Colonel in the Mexican army pursuing revolutionary Tomas Milian (with music by Ennio Morricone). He plays Louis XVIII in the Russian-Italian co-production WATERLOO (1970).

Welles has a cameo in John Huston’s THE ROOTS OF HEAVEN (1958) about an Englishman’s crusade to protect elephants from slaughter in Africa. I saw the beginning of the movie years ago and I’m pretty sure I saw Welles’ entire part, but I don’t remember who he played. He also has an early cameo in Huston’s MOBY DICK (1956). (Welles would later direct Huston in THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND.) Welles had a pretty good run of acting roles around that time, including a racist, power-hungry rancher in Jack Arnold’s modern western, MAN IN THE SHADOW (1957); as Southern patriarch Will Varner in the William Faulkner adaptation, THE LONG HOT SUMMER (1958); and substantial roles in Richard Fleischer’s COMPULSION (1959), in which he plays a character based on famed criminal defense lawyer Clarence Darrow who defends characters based on the 1920s “thrill killers,” Leopold and Loeb; Lewis Gilbert’s FERRY TO HONG KONG (1959), in which he plays a boat captain in Hong Kong forced to contend with an unruly passenger (Curt Jurgens) remanded to his boat by the Hong Kong police; and CRACK IN THE MIRROR (1960), a romantic triangle/courtroom drama in which he, Bradford Dillman and Juliette Greco all play dual roles. I’ve seen MAN IN THE SHADOW, LONG HOT SUMMER and COMPULSION before, but would love to see them all again. FERRY TO HONG KONG and CRACK IN THE MIRROR both sound intriguing enough to be worth seeing despite their lack of any praiseworthy reputation.

Coming after these films, I’ve seen the aforementioned THE V.I.P.S, in which Welles seems to be channeling, to great comic effect, Russian-born character actor/director Gregory Ratoff (mentioned above in connection to BLACK MAGIC), but I’ve never seen LAFAYETTE from the same year. Of his later acting jobs, I’ve never seen the Yugoslavian WWII epic, THE BATTLE OF NERETVA (1969), in which Welles plays a Chetnik senator as part of an all-star cast that also includes Yul Brynner, Franco Nero, Curt Jurgens and Hardy Kruger, with music by Bernard Herrmann, the composer who Welles initially brought to Hollywood from New York to compose the score for CITIZEN KANE. I’ve yet to see Henry Jaglom’s A SAFE PLACE (1971), Claude Chabrol’s TEN DAYS WONDER (1971), Brian de Palma’s GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT (1972) or the French-Italian-Spanish-English-German production of TREASURE ISLAND (1972), in which he played Long John Silver, although IMDB says he was dubbed over by voice actor extraordinaire Robert Rietty (who died last month at the age of 92) in “some versions.” I did see Welles’ performance as a judge in the controversial James M. Cain incest story, BUTTERFLY (1982), starring Stacy Keach and Pia Zadora, with music by Ennio Morricone, a bizarre film but with a great supporting cast (look it up—it includes June Lockhart and Ed McMahon!). I also saw Welles’ last acting performance—in Henry Jaglom’s SOMEONE TO LOVE (1987), in which he sits in the back of a theater and pontificates. Some bits from that movie can be seen in this Leonard Maltin clip from the July 11, 1988 episode of ENTERTAINMENT TONIGHT:

There’s a book called Orson Welles Interviews and it’s part of the University Press of Mississippi series of books called “Conversations with Filmmakers.”

I reviewed the book on Amazon and here is a link to that review:

There’s a great section in the second of the two Andre Bazin interviews with Welles in the book that I’d like to quote here that sums up his philosophy toward his art and his working methods (at least as they were in 1958, when the interview was conducted):

Experimenting is the only thing I’m enthusiastic about. I’m not interested in art works, you know, in posterity or fame, only in the pleasure of experimentation itself. It’s the only domain in which I feel that I am truly honest and sincere. I’m not at all devoted to what I do. It truly has no value in my eyes. I’m profoundly cynical about my work and about most works I see in the world. But I’m not cynical about the act of working on material. It’s difficult to explain. We professional experimenters have inherited an old tradition. Some of us have been the greatest of artists, but we never made our muses into our mistresses. For example, Leonardo considered himself to be a scientist who painted rather than a painter who was a scientist. Don’t think that I compare myself to Leonardo; I’m trying to explain that there’s a long line of people who evaluate their work according to a different hierarchy of values, almost moral values. So I don’t go into ecstasy when I’m in front of an artwork. I’m in ecstasy in front of the human function, which underlies all that we make with our hands, with our senses, etc. Our work, once it is finished, doesn’t have the importance that most aesthetes give it. It’s the act that interests me, not the result, and I’m only taken in by the result when it reeks of human sweat, or of a thought.

I had hoped to see much more of Welles’ output in preparation for this piece, but I’d gotten preoccupied with another blog entry I’m working on that thoroughly distracted me until I realized only yesterday that Welles’ centennial was coming up today. So I had to scramble to get what material I could for this piece. I had hoped to watch CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT again–for the first time in about 40 years, but I’ll have to save that for later. It’s easily my favorite of his Shakespeare adaptations. And I would like to have re-watched his three other “masterpieces,” besides CITIZEN KANE, of course: THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, LADY FROM SHANGHAI, and TOUCH OF EVIL, neither of which I’ve seen in over a decade.

Here’s a link to my IMDB review of Welles’ essay film on Gina Lollobrigida, “Viva Italia: Portrait of Gina”:

Orson Welles at Large: Portrait of Gina

You can find this piece on YouTube in multiple parts and incomplete, under the title, “Viva Italia (Portrait of Gina).”

And here’s a link to my friend Judith Trojan’s blog entry on a documentary about Welles’ infamous 1938 “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast:

Celebrate the 70th Anniversary of War of the Worlds tonight on PBS

Finally, there is so much good Welles material on YouTube that I’ll just provide a link to one episode of” Orson Welles’ Sketchbook” (1955, BBC) to give you a start. You can easily find the other five segments of this delightful series of Welles telling stories to the camera on the same channel that provides this:

Bravo, Brian!

Incidentally, I saw that New Yorker double feature along with young Jeannie. She loved Kane and Pierre Fresnay.

Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind is on Netflix, for whomever wants to check it out.