Recently, a thread on the Home Theater Forum asked participants for their “all-time favorite movie process.” While others picked things like IMAX, 3-D, Cinerama, Todd-AO, Vistavision, Ultra Panavision 70 and the like, I was the only one to declare Academy ratio black-and-white as my favorite “process,” although “format” would be a more appropriate term. Here are the images I posted:

The Academy ratio of 1.37:1, sometimes referred to as 4:3, was the standard ratio for the motion picture frame from 1932 right up until the conversion to widescreen began in earnest in 1953, after which wider aspect ratios were used to give audiences a sense that they were getting something they couldn’t see on television. Television had adopted the ratio of 1.33:1, which had been the standard for movies before 1932 and was close enough to the Academy ratio to allow movies shot in that ratio to air on television without necessitating cropping (not that the full image was ever exactly shown, but that’s another story).

Once widescreen became the norm for theatrical motion pictures, it meant that TV airings of movies made from 1953 on meant, in most cases, cropping off the sides of the image (although sometimes “open matte” prints were used, meaning that the parts of the image cropped off for theaters was now visible on the small screen). The standard TV ratio remained the same until the switch-over from standard definition to high-definition in 1998. For more information, here’s a link to a website that offers some explanation: http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/widescreen/evolution.htm.

Here is an illustration comparing the three most often-used aspect ratios. I would have used different images as examples, but this is the best I could find:

The Academy ratio frame seems to me to be the perfect size for the kinds of black-and-white compositions that continue to strike me as beautiful and artful. When the filmmaker doesn’t have to worry about “filling up” the frame, he can stage the actors in more engaging and meaningful ways. And when the filmmaker doesn’t have to worry about how different colors showed up on color film and the extra light required for the early Technicolor cameras, he could concentrate on light, shading and contrast for dramatic effect, as well as employing sets, props, costumes, and backdrops to make his compositions more effective and create a believable space for the actors.

Without black-and-white film and the reliance on light, shadow and contrast for psychological effects, how would we have gotten film noir?

All of this struck me as I came off of a wave of viewings of Academy ratio black-and-white films from both Hollywood and Japan that were either first-time viewings or repeat viewings of films I hadn’t seen in years. I’ve done this kind of viewing regularly over the years, so it’s not a sudden rediscovery. It’s just that it finally dawned on me that so many of my most satisfying viewing experiences have occurred while watching black-and-white movies, especially those made before 1953. And when I make lists of “Favorites” and “Best Films,” a large portion of them are Academy ratio b&w films. Here are some films that are considered among the best Hollywood films ever made, as well as being among my all-time favorites (bolded titles pictured below):

KING KONG, THE GRAPES OF WRATH, CITIZEN KANE, THE MALTESE FALCON, CASABLANCA, SHADOW OF A DOUBT, DOUBLE INDEMNITY, THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE, THE BIG SLEEP, MY DARLING CLEMENTINE, OUT OF THE PAST, RED RIVER, TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE, WHITE HEAT, SUNSET BOULEVARD, A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A PLACE IN THE SUN and many more.

Notice how the actors, playing strongly-etched characters, are the dominant elements in each frame.

Look at all the great filmmakers who did all or most of their best work in Academy ratio b&w:

John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Orson Welles, John Huston, Raoul Walsh, Fritz Lang, Josef von Sternberg, Ernst Lubitsch, Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse, Jean Renoir, and Max Ophuls, to name just a few.

From IMDB: Orson Welles “Considered black and white to be ‘the actor’s best friend,’ feeling that it focused more on the actor’s expressions and feelings than on hair, eye or wardrobe color.”

I once made a list of 100 Essential Black-and-White Movies and thought of posting it here, but I’d rather hold off on a bout of lengthy list-making and instead look at particular frames of film and try to illustrate why the Academy ratio b&w frame lends itself to so many great movies.

Here are two scenes from Howard Hawks’ THE BIG SLEEP (1946), a private eye thriller based on a novel by Raymond Chandler and starring Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe. In the first set of frames, Marlowe visits small-time grifter Joe Brody (Louis Jean Heydt) to pressure him for information on the blackmail of his client and the murder of the blackmailer, only to be interrupted, first by Brody’s girlfriend (Sonia Darrin) and then by the daughter (Lauren Bacall) of his client. As the scene plays out, Hawks arranges the characters in the scene to reflect the shifting power relationships among them as one or another gets the upper hand, with or without guns, a maneuver that gets complicated when more characters, with more guns, show up.

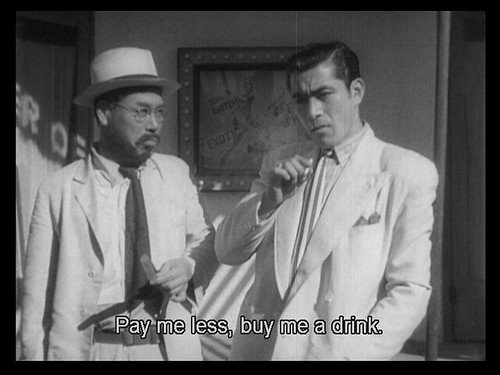

Later, Marlowe has an encounter with a “little man” who’s been following him and who finally introduces himself when he comes to Marlowe’s aid after he’s been beaten by thugs working for a gambler who wants Marlowe to stop snooping. The man, Harry Jones, referred to as “Jonesy” (Elisha Cook Jr.), has information that Marlowe needs and thus has a certain amount of power over him as he stands over Marlowe and bargains with him, “one right guy to another,” as Jonesy puts it.

Later, when Marlowe goes to meet Jonesy at their pre-arranged meeting place, he stumbles on Jonesy being confronted by the gambler’s chief henchman Canino (Bob Steele) and watches helplessly in silence from an adjoining room as Canino forces Jonesy to “have a drink” which turns out to be poison. Hawks employs not just the actors, but the office design, furniture, late-night lighting, and the coats and hats the men wear to define character and make dramatic points.

It’s one of the pivotal scenes in the movie and provides much of the motivation for Marlowe’s later actions as he seeks justice for poor little Jonesy, a hapless but well-intentioned man who took the fall to save a woman who was only using him. “Funny little guy. Harmless. I liked him,” recalls Marlowe. I can’t imagine this scene playing out quite as well in color and widescreen.

Academy ratio compelled filmmakers to focus on the human element, while black-and-white allowed them to single out the most dramatic elements in the frame.

Here are shots from other favorite pre-1953 black-and-white films:

THE SCARLET EMPRESS (1934), Josef von Sternberg’s baroque, borderline surreal chronicle of the rise to power of Russia’s Catherine the Great (Marlene Dietrich):

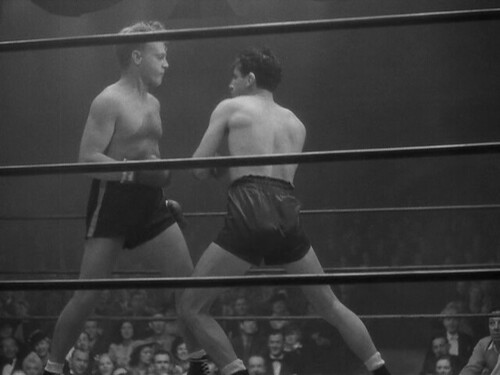

Anatole Litvak’s CITY FOR CONQUEST (1940), starring James Cagney, Ann Sheridan and Arthur Kennedy, is a celebration of the vitality and creative spirit of New York in the 1930s, from the Lower East Side to Times Square to Carnegie Hall, charting three characters’ varying fates in the worlds of boxing, vaudeville and concert music:

JANE EYRE (1943), Robert Stevenson’s gothic romance, based on Charlotte Bronte, about the love between a domineering landowner (Orson Welles) in pre-Victorian England and the orphaned governess (Joan Fontaine) he’s hired to tutor his young ward:

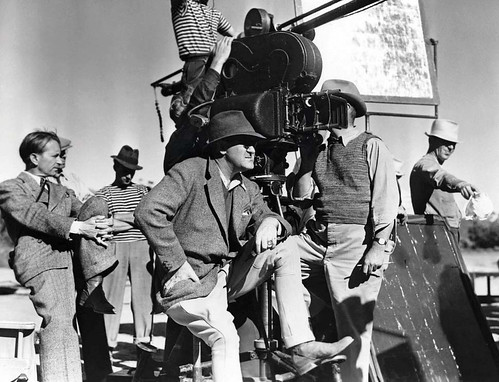

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE (1946), John Ford’s myth-making chronicle of Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) and Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) which posits their epic takedown of the Clanton clan at the O.K. Corral as the decisive event that brought law and civilization to Tombstone, Arizona. The saga is enhanced by location shooting on a set built against the awe-inspiring backdrop of Monument Valley, creating some of the most iconic cinematic images of the west:

Jacques Tourneur’s OUT OF THE PAST (1947) is a film noir thriller with Robert Mitchum as a basically decent private eye who gets caught up in a toxic love triangle spewing out a web of lust, deception and betrayal:

In PORTRAIT OF JENNIE (1948) director William Dieterle mixes location shots in New York City with studio-created close shots to tell an otherworldly love story involving a struggling artist (Joseph Cotten) and the mysterious girl (Jennifer Jones) he meets in Central Park in Depression-era New York:

In WHITE HEAT (1949), a crime saga about an unrepentant bandit (James Cagney) and his final exploits, director Raoul Walsh mixes location shots of the criminal gang at work and scenes shot at an actual prison with film noir compositions in enclosed spaces foreshadowing the treachery of those closest to him as his wife (Virginia Mayo) and his top lieutenant (Steve Cochran), plan on a future without him and the friend he picked up in prison turns out to be an undercover treasury agent (Edmond O’Brien).

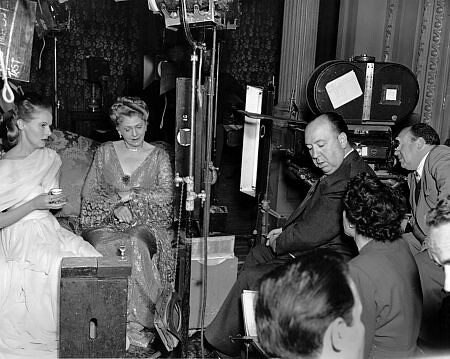

Alfred Hitchcock’s STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1951), starring Farley Granger and Robert Walker, tells a dark tale of an innocent man caught up in a “murder swap” scheme hatched by a deranged traveler he meets on a train. The two men’s fates are intricately entwined as one tries to avoid being charged for the murder the other one commits, while the murderer expects the first man to commit a murder on his behalf.

And from Japan, in which Academy ratio continued to be the norm up to 1957:

Akira Kurosawa’s DRUNKEN ANGEL (1948):

Mikio Naruse’s GINZA COSMETICS (1951):

Kenji Mizoguchi’s LIFE OF OHARU (1952):

Ishiro Honda’s GOJIRA (1954):

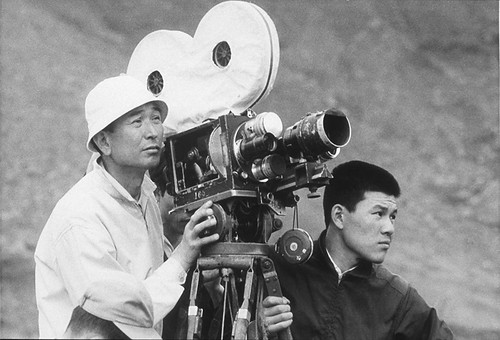

Akira Kurosawa’s THE SEVEN SAMURAI (1954):

Yasujiro Ozu’s EARLY SPRING (1956):

Kon Ichikawa’s THE BURMESE HARP (1956):

Tatsuo Yamada’s TRAITORS OF THE DATE CLAN (1957):

What we see in all these films is a sheer love of filmmaking and the use of black-and-white Academy ratio film to capture human emotion in visual terms and dramatize stories of believable and compelling characters in inventive and artistic ways. The best of these filmmakers created their own unique pictorial style that was quite distinct from each of the others. Many of them went on to do equally great works in color and wider aspect ratios, e.g. John Ford’s THE SEARCHERS, Howard Hawks’ RIO BRAVO and Alfred Hitchcock’s VERTIGO. But for many of the filmmakers cited above, their best works were in black-and-white Academy ratio.

I had the good fortune to see many of these films on the big screen during the heyday of New York’s repertory theaters, but I realize that may not be an option for most fans of classic films, nor is it much of an option even in New York anymore. While most of the works listed here are available on DVD and other formats, there are, sadly, only a handful of TV channels left that still run movies shot in Academy ratio black-and-white. On cable, these include Turner Classic Movies, the Fox Movie Channel, and Starz Encore Western. There are digital channels sprinkled along the spectrum, with titles like ME-TV and Decades, that continue to run such programming also. But it’s a far cry from the days when we only had seven TV channels on the dial and all seven ran Academy ratio black-and-white movies regularly at some point during the day or night. I should know–I saw plenty of them on the set seen in the background of this childhood photo:

I’ve been thinking about this, Brian, ever since you told me you were going to write about it on your blog. The result, I think, is one of your most interesting entries with lots of food for thought. It is most refreshing and stimulating that you are dealing here in carefully thought out detail with the very nature of story-telling on film, when most online writing about movies seems to be discussing plays or novels! However, for me, I can’t imagine limiting my preferences to a particular format or process, anymore than I could confine my viewing to a particular period of time. I am still thrilled by Lumiere’s Train Arriving at a Station as I am by most of the 40s films you cite and by recent pictures like Master and Commander and The Age of Innocence. The great filmmakers have always made great films in whatever format is the norm in their time. What strikes me about your list of great filmmakers who did most of their best work in academy ratio is how many of them learned their craft and their art in the silent era. Thus Hawks, Hitchcock, and Renoir had been working in very close to academy ratio since the 20s; and Ford, Walsh, Lang, and Lubitsch since the teens! That’s a lot of practice in telling a story visually, and these people well as many others did not abandon their hard-earned skill with the coming of sound, color, or widescreen! Thanks, Brian, for another great blog.

Manage